Fees and fines are an important part of Tennessee’s criminal justice system – both to punish criminal acts and fund an essential government function. This report dives deeper into one item on our list of potential policy options to address the side-effects of fees, fines, and other legal financial obligations (LFOs). Specifically, it looks at how a person’s ability to pay fees and fines factors into what they ultimately owe and highlights several options for state-level policy change.

Prior reports walk through the 360+ LFOs people can accrue in the state’s criminal justice system, their effects on different stakeholders, the revenue they generate for our state and local governments, and opportunities to improve data collection.

Key Takeaways

- The effect that fees, fines, and other legal financial obligations have on people required to pay them (and the justice system overall) largely depends on their ability to pay them.

- A patchwork of provisions in Tennessee code offers wide flexibility but little consistency in how courts should address defendants’ ability to pay fees and fines.

- Judges across the state vary in when and how they determine a defendant’s ability to pay.

- The judicial discretion baked into current law recognizes that each case is unique but can also generate unequal outcomes that diverge by jurisdiction and/or defendants’ economic status.

- Options to address these challenges include gathering better data on current practices and making state law more consistent. Policymakers could also consider graduated fines.

Terminology

Criminal justice fees and fines, criminal justice financial obligations, legal financial obligations, and criminal justice debt all refer to costs a person may owe as they move through the criminal justice system. These terms do not include the costs of private legal representation.

Background

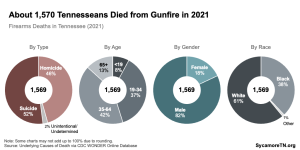

People can accrue a multitude of fees and fines as they move through Tennessee’s criminal justice system (Figure 1). The amounts owed depend on the offense, the actors involved, and a case’s ultimate outcome, but they can add up quickly. (1) While publicly available data is limited, it is not unusual for total debts to reach several thousand dollars or more. (2)

The impact on people required to pay fees and fines largely depends on their ability to do so. Defendants’ different economic backgrounds necessarily mean financial penalties are not felt evenly. (3) Due to the demographics of crime and policing, the people most likely to accrue legal financial obligations tend to be relatively poor. (4) (5)

Figure 1

For people less able to pay, fees and fines can prolong their involvement in the criminal justice system and make it harder to get ahead. (6) For example, someone reentering society from incarceration with unpaid debts and a revoked driver’s license may have more trouble securing a job, housing, and financial stability – all associated with reduced recidivism. (7) (8)

Fees and fines that people don’t have the ability to pay can also put more burden on the justice system itself. (9) (1) A majority of criminal fees and fines go uncollected, at least in part because many people who owe them do not have a lot of money. (6) (9) The unpaid debts can result in additional court hearings, supervision costs, and even incarceration – all of which may turn this potential revenue into a net cost instead. Meanwhile, the time and resources spent trying to collect unpaid debt can also become a drain on local budgets. (10)

Ability-to-Pay in Tennessee State Law

A patchwork of provisions in Tennessee code offers wide flexibility but little consistency in how courts should address defendants’ ability to pay fees, fines, and other legal costs. Statute lays out many instances – some broad, some specific – in which a court may consider an individual’s financial circumstances when deciding about certain criminal fees, taxes, fines, and restitution.

Inconsistent and Ambiguous

State law includes at least six distinct frameworks for officials to use in different situations to assess a criminal defendant’s ability to pay (Appendix Table 1). For example, to receive appointed counsel, an indigent defendant is one who cannot afford a competent attorney based on a judge’s review of the individual’s income and assets, customary attorneys’ fees, and federal poverty guidelines. (11) To qualify for reduced electronic monitoring costs, however, a person is deemed indigent if their income is below 185% of the federal poverty line. (12)

Dozens of clauses in state law allow or require courts to base various financial obligations on hardship, indigency, and ability to pay – but do not define those terms (Appendix Table 1). For example, judges can waive or modify debts based on a defendant’s ability to pay, future ability to pay, financial situation or condition, hardship, having sufficient funds to pay, or having anticipated future funds to pay. Examples of when these and other broad and undefined terms apply include:

- Modification of monthly community supervision fees for probationers and parolees. (13)

- Eligibility for and amount of bail bond for defendants released from jail pre-trail. (14)

- Amount of any required fines and/or restitution. (15)

- Suspension of litigation taxes or eligibility for community service in lieu of litigation taxes. (16)

- Cost of GPS tracking, ignition interlock devices, and drug/alcohol monitoring for pre-trial defendants released on bail, defendants granted pre-trial diversion, DUI offenders, people under community supervision, and other defendants. (17)

State law is often ambiguous about if, when, and how to review someone’s ability to pay and subsequently waive or modify financial obligations. For example, judges can modify mandatory minimum fines for certain DUI and drug charges if a person is declared indigent using a set of specific factors. However, the law does not actually compel judges to review that person’s ability to pay. Neither does it say how to interpret the specified criteria or what standards should guide the reduction or waiver of minimum fines when a judge does declare someone indigent. (18)

The law sometimes applies different standards and criteria to similar financial obligations. For example, certain types of transcript fees can be waived if a person “does not have sufficient funds” to pay them. (19) Suspending other similar types of fees, however, depends on a definition of indigency that considers a defendant’s ability to afford an attorney. (20)

Piecemeal Approach Obscures Total Debt

Few of the relevant provisions in state law recognize the potential that people will face multiple legal financial obligations. In most instances, ability-to-pay reviews are mentioned in the context of a specific type of legal cost without consideration for the dozens of other obligations any given defendant might owe.

Finally, some ability-to-pay rules only apply after a person falls behind on their debts and faces legal consequences. For example, the only time state law explicitly calls for a review of a defendant’s total debt from fines, litigation taxes, and other costs is after they have defaulted and risk suspension of their driver’s license. (20)

Determining Ability-to-Pay in Practice

Judges across the state vary in how they determine a defendant’s ability to pay LFOs. Different judges require different kinds and amounts of personal financial information. For example, some use the Supreme Court’s affidavit of indigency for most ability-to-pay decisions. Others have reportedly asked for informal self-attestations or social security numbers. (2) (21) (22) In at least six recent cases, the state’s Criminal Courts of Appeal found that lower courts failed to adequately consider a person’s ability to pay when setting restitution. (23) (24) (25) (26) (27) (28) (29) Full dockets and a perceived need to process them quickly may also contribute to inadequate or inconsistent reviews. (2) (21) (22)

Not all judges use the same approach to change an indigent person’s legal financial obligations. Under state law, judges can either waive LFOs for indigent defendants or reduce them to some lesser amount. Judges might also convert criminal debts into civil debt, which waives the criminal consequences without reducing the amount owed. These civil debts carry new costs and consequences of their own, however. Based on Sycamore’s conversations with current and former local officials in Davidson and Shelby Counties, these practices may vary from one county to the next and sometimes even from courtroom to courtroom in the same county.

There is no consistent point in a case when the court reviews a defendant’s ability to pay legal costs. For example, the initial indigency determinations required for access to a public defender do not necessarily apply to other financial obligations. Unless the law explicitly requires one, defendants must request a review of their ability to pay fees and fines. Sometimes, defendants must establish their indigency multiple times during the consideration of a case. (2)

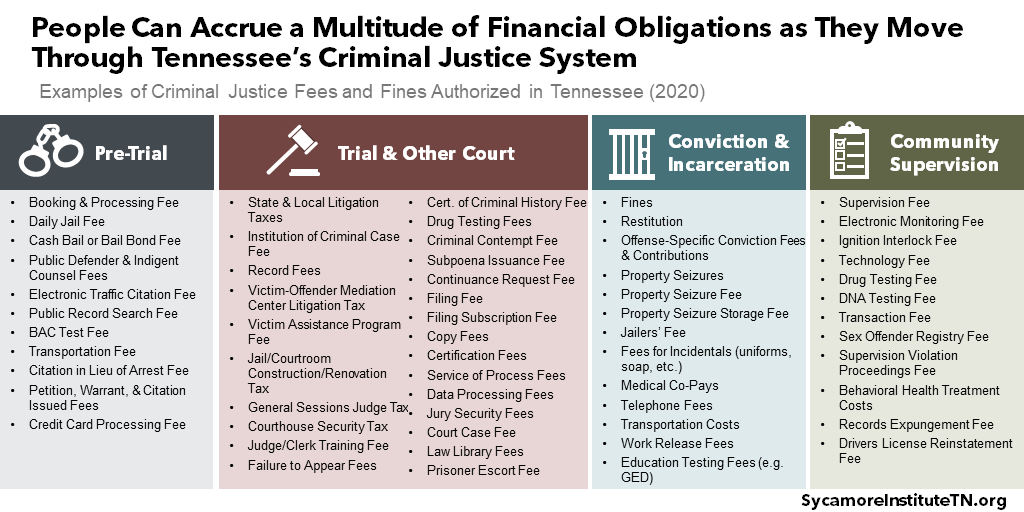

Data on public defender administration fees shed light on the variation in practices across the state. People deemed indigent and assigned a public defender owe a $50 administrative fee that the court can waive, reduce, or raise to a maximum of $200. Courts must report to the state how often they waive these fees. (31) According to the available data, Tennessee judges waived administrative fees for about half of people who used public defenders in 2020 (Figure 2). However, the rate varies widely by county. Over 90% of public defender fees were waived in 19 counties while less than 10% were waived in 14 counties. (32)

Figure 2

The Trade-Offs of Current Law and Practice

The judicial discretion baked into current law recognizes that each case is unique but can also generate unequal outcomes. Current law and court rules allow considerable flexibility in determining a defendant’s ability to pay most legal financial obligations. This permits individualized judgments of each circumstance but can also lead to inconsistent outcomes. For example, two people with the same offenses and ability to pay may face different financial consequences based on which jurisdiction or judge hears their cases. Likewise, some people with adequate financial resources may see their debts waived while others with less or no ability to pay do not.

Policy Options to Address These Trade-Offs

State policymakers could explore a number of ways to address any unwanted side-effects of current law and practice.

Better Data on Current Practices

Better statewide data on the practices used to determine defendants’ ability to pay LFOs would shed light on which practices are exceptions and which are the rule. Much of what we know about inconsistencies in how, when, and what judges consider and decide is based on anecdotal information from a handful of counties across the state. Better data would provide a clearer picture of the degree and range of variation under current law.

More Standards and Consistency for Assessing Ability to Pay

Policymakers could encourage or require more consistency in when and how courts review and make accommodations for a defendant’s financial situation. Options range from supporting the voluntary adoption of more uniform practices to mandating specific actions, criteria, standards, and timelines. (33) (34) (35) Each option will come with its own set of trade-offs. For example, making judges proactively assess a person’s ability to pay could require more court resources on the front end. On the back end, it could also reduce the negative impact of unpaid debts on both defendants and the justice system itself.

Current state requirements already provide some guideposts for any changes to make standards more uniform. For example, the Tennessee Supreme Court defines indigent as under 125% of the poverty level under one of its indigency standards. (22) (36) It also provides uniform affidavit forms for implementing this and two other specific indigency standards laid out in law. (37) (38) (39) Meanwhile, the state employs numerous specific income and asset eligibility qualifications for programs designed to serve indigent individuals. (40) (41) (42) (43) (44) (45)

Approaches from other states that might also provide examples for Tennessee policymakers include:

- The Ohio Supreme Court publishes a bench card or “cheat sheet” with guidelines and the factors judges should consider when making decisions about fines and other legal financial obligations. (46)

- Texas requires courts to conduct assessments of ability-to-pay for all fine-only offenses and requires either a payment plan, fine waiver, or alternative sentence (e.g. community service) if an individual is unable to pay. (47)

- Statutes in at least seven other states provide a uniform default definition of indigency while giving judges the flexibility to use a different standard. The thresholds for those standards vary between 125-200% of poverty. (1) (48)

Graduated Fines

Lawmakers could consider switching to a sliding-scale system of fines that automatically vary based on a defendant’s financial resources. Traditionally, financial penalties for crimes are set based on the offense alone. Some jurisdictions instead use a system known as “day fines” that factor a defendant’s financial situation into any penalties they might face. While effective administration may require greater resources, jurisdictions that have experimented with day fines in the U.S. generally found them to increase both collection rates and amounts. (9) (49) (50) (51) (52)

Parting Words

In both statute and practice, there is little consistency to how Tennessee’s criminal courts consider someone’s ability to pay whatever fees and fines our justice system might levy on them. As a result, it is not uncommon for similar cases to yield unequal outcomes that diverge by geography and/or defendants’ economic status. Reforms to make this process more consistent and transparent could have a range of benefits for public safety, public finances, and public trust.

References

Click to Open/Close

- Barrie, Jennifer, et al. Tennessee’s Court Fees and Taxes: Funding the Courts Fairly. Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations (TACIR). [Online] January 26, 2017. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tacir/documents/2017_CourtFees.pdf

- Tennessee Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Legal Financial Obligations in the Tennessee Criminal Justice System. U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. [Online] January 15, 2020. https://www.usccr.gov/pubs/2020/01-15-TN-LFO-Report.pdf

- Garoupa, Nuno and Mungan, Murat. Optimal Imprisonment and Fines with Non-Discriminatory Sentences. Economic Letters. [Online] 182 2019. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3382839

- Shapiro, Joseph. As Court Fees Rise, the Poor are Paying the Price . National Public Radio. [Online] May 19, 2014. https://www.npr.org/2014/05/19/312158516/increasing-court-fees-punish-the-poor

- Bannon, Alicia, Nagrecha, Mitali and Diller, Rebekah. Criminal Justice Debt: A Barrier to Reentry. The Brennan Center. [Online] October 4, 2010. https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/2019-08/Report_Criminal-Justice-Debt- A-Barrier-Reentry.pdf

- Martin, Karin D., Smith, Sandra Susan and Still, Wendy. Shackled to Debt: Criminal Justice Financial Obligations and the Barriers to Re-Entry They Create. New Thinking in Community Corrections. [Online] January 17, 2017. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/249976.pdf

- Bender, Alex, et al. Not Just a Ferguson Problem: How Traffic Courts Drive Inequality in California. [Online] 2015. https://lccrsf.org/wp-content/uploads/Not-Just-a-Ferguson-Problem-How-Traffic-Courts-Drive-Inequality-in-California-4.8.15.pdf

- Salas, Mario and Ciolfi, Angela. Driven by Dollars: A State-by-State Analysis of Driver’s License Suspension Laws for Failure to Pay Court Debt. Legal Aid Justice Center. [Online] September 15, 2017. https://www.justice4all.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Driven-by-Dollars.pdf

- Menendez, Matthew and Eisen, Lauren-Brooke. The Steep Costs of Criminal Justice Fees and Fines. The Brennan Center. [Online] November 21, 2019. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/steep-costs-criminal-justice-fees-and-fines

- Worthington, Paula R. Best Practices: Reforming Fine & Fee Policies in the Criminal Justice System. PFM Center for Justice & Safety Finance. [Online] August 2020. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f0735ceb487f10af7ea8372/t/5f3bfc5eb7b82234a999fd4e/1597766750639/Fines+and+Fees+Best+Practices_August+2020_Harris+Center.pdf

- State of Tennessee. Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-14-202. [Online] 2021. Accessed on October 7, 2021 via Lexis.

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 55-10-419(d). [Online] 2021. Accessed on October 7, 2021 via Lexis.

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-35-303(p)(6)(A) and 40-35-303(i)(l). [Online] 2021. Accessed on October 7, 2021 via Lexis .

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-11-118(b)(2). [Online] 2021. Accessed on October 7, 2021 via Lexis .

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-35-207(a)(7) and 40-35-304. [Online] 2021. Accessed on October 7, 2021 via Lexis .

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-25-123(b). [Online] 2021. Accessed on October 7, 2021 via Lexis .

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-11-118(d)(2)(B), 40-11-148(b)(2)(B), 40-11-152(h), 40-15-105(a)(2)(l), 40-28-117(2)(b), 40-33-211(c)(3)(A), 40-33-211(f)(3)(A), 55-10-402(d)(2), 55-10-402(h)(7)(a), and 55-10-402(h)(7)(c). [Online] 2021. Accessed on October 7, 2021 via Lexis .

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 39-17-428(d)(1) and 55-10-403(b). [Online] 2021. Accessed on October 7, 2021 via Lexis .

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-14-312. [Online] 2021. Accessed on October 7, 2021 via Lexis .

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-24-105(b)(6). [Online] 2021. Accessed on October 7, 2021 via Lexis .

- Indigent Representation Task Force. Liberty & Justice for All: Providing Right to Counsel Services in Tennessee. Tennessee Supreme Court. [Online] April 2017. http://www.tncourts.gov/sites/default/files/docs/irtfreportfinal.pdf

- Tennessee Supreme Court. Rule 29: Uniform Civil Affidavit of Indigency. [Online] https://www.tncourts.gov/rules/supreme-court/29

- The Sycamore Institute’s analysis of Criminal Court of Appeals opinions. Specific examples cited below. [Online] [Cited: September 21, 2021.] Search conducted via https://www.tncourts.gov/search/apachesolr_search/ability%20to%20pay%20restitution?filters=type%3Aopinions

- Court of Criminal Appeals of Tennessee at Nashville. State of Tennessee v. David Allan Bohanon (No. M2012-02366-CCA-R3-CD). [Online] October 25, 2013. https://www.tncourts.gov/sites/default/files/dbohanonopn.pdf

- Court of Criminal Appeals of Tennessee at Jackson. State of Tennessee v. Anita H. Lane (No. W2017-01716-CCA-R3-CD). [Online] September 10, 2018. https://www.tncourts.gov/sites/default/files/lane_anita_h_opn.pdf

- Court of Criminal Appeals of Tennessee at Knoxville. State of Tennessee v. Jason Monroe Griffith (No. E2020-00259-CCA-R3-CD). [Online] February 25, 2021. https://www.tncourts.gov/sites/default/files/jason_monroe_griffith_cca_opinion.pdf

- Court of Criminal Appeals of Tennessee at Nashville. State of Tennessee v. Ida Veronica Thomas (No. M2019-02137-CCA-R3-CD). [Online] January 1, 2021. https://www.tncourts.gov/sites/default/files/thomas.ida_.opn_.pdf

- Court of Criminal Appeals of Tennessee at Jackson. State of Tennessee v. Trenton Ray Forrester (No. W2018-01947-CCA-R3-CD). [Online] August 27, 2019. https://www.tncourts.gov/sites/default/files/forrester_trenton_ray_opn.pdf

- Court of Criminal Appeals of Tennessee at Nashville. State of Tennessee v. Tyson B. Dodson (No. M2018-01087-CCA-R3-CD). [Online] August 21, 2019. https://www.tncourts.gov/sites/default/files/dodson.tyson_.opn_.pdf

- Tate, Deborah Taylor. Adminstrative Fee for Appointed Counsel Calendar Year 2020. Tennessee Administrative Office of the Court. [Online] March 5, 2021. https://tncourts.gov/sites/default/files/docs/status_report_to_general_assembly_2020.pdf

- State of Tennessee. Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-14-103: Right to Appointed Counsel – Administrative Fees. [Online] Accessed on October 8, 2021 from Lexis.

- Tennessee Administrative Office of the Court. Adminstrative Fee for Appointed Counsel Calendar Year 2020. [Online] March 5, 2021. https://tncourts.gov/sites/default/files/docs/status_report_to_general_assembly_2020.pdf

- National Criminal Justice Debt Initiative. Confronting Criminal Justice Debt: A Guide for Policy Reform. The Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School. [Online] 2017. https://cjdebtreform.org/sites/criminaldebt/themes/debtor/blob/Confronting-Crim-Justice-Debt-Guide-to-Policy-Reform.pdf#page=30

- National Task Force on Fines, Fees, and Bail Practices. Principles on Fines, Fees, and Bail Practices. National Center for State Courts. [Online] February 2021. https://www.ncsc.org/__data/assets/pdf_file/0021/61590/Principles-on-Fines-Fees-and-Bail-Practices-Rev.-Feb-2021.pdf

- National Network on Fines, Fees, and Bail Practices. At-a-Glance Checklist for Ability to Pay Determination Hearings. National Center for State Courts. [Online] May 11, 2021. https://www.ncsc.org/__data/assets/pdf_file/0032/64499/At-A-Glance-Checklist-for-Ability-to-Pay-Determination-Hearings-5-11-2021-002.pdf

- Legal Services Corporation. Income Level for Individuals Eligible for Assistance (45 CFR 1611). [Online] January 28, 2021. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/01/28/2021-01815/income-level-for-individuals-eligible-for-assistance

- Tennessee Administrative Office of the Courts. Uniform Affidavit of Indigency. [Online] [Cited: September 21, 2021.] https://www.tncourts.gov/sites/default/files/uniform_affidavit_of_indigency.pdf.\

- —. Uniform Affidavit of Indigency for Purposes of Electronic Monitoring Indigency Fund. [Online] July 2019. https://www.tncourts.gov/sites/default/files/docs/july_2019_-emif_indigency_affidavit_and_order.pdf

- —. Uniform Civil Affidavit of Indigency. [Online] [Cited: September 21, 2021.] https://www.tncourts.gov/sites/default/files/uniform_civil_affidavit_of_indigency.pdf

- State of Tennessee. Tenn. Code Ann. § 71-5-106. Determination of Eligibility for Medial Assistance. [Online] 2021. Accessed on October 8, 2021 from Lexis.

- TennCare. Eligibilty Reference Guide. [Online] July 2021. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents/eligibilityrefguide.pdf

- Tennessee Department of Health. Uninsure Adult Healthcare Safety Net Annual Report. [Online] 2020. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/health/program-areas/reports_and_publications/Safety_Net_Report_FY20.pdf

- Tennessee Department of Human Services. Vocational Rehabilitation: Eligibility. [Online] [Cited: October 8, 2021.] https://www.tn.gov/humanservices/ds/vocational-rehabilitation/vr-eligibility.html

- —. Supplemental Nutrition Income (SNAP): Eligibility INformation. [Online] [Cited: October 8, 2021.] https://www.tn.gov/humanservices/for-families/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap-eligibility-information.html

- —. Child Care Certificate Program: Income Eligibility Limits and Parent Co-Pay Fee Table. [Online] 2020. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/human-services/documents/Income%20Eligibility%20Limits%20and%20Parent%20Co-Pay%20Fee%20Table%20Fiscal%20year%202020-2021.pdf

- The Supreme Court of Ohio. Collection of Court Costs and Fines in Adult Trial Courts. [Online] May 2021. https://www.supremecourt.ohio.gov/Publications/JCS/finesCourtCosts.pdf

- Holik, Haley and Levin, Marc. Confronting the Burden of Fines and Fees on Fine-Only Offenses in Texas: Recent Reforms and Next Steps. Texas Public Policy Foundation. [Online] April 2019. https://www.texaspolicy.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Holik-Levin-Confronting-the-Burden-of-Fines-and-Fees1.pdf

- State of Nevada. Nevada Assembly Bill 434: Certain Traffic Offenses; Payment of Fines and Fees; Community Service. [Online] June 2019. https://legiscan.com/NV/text/AB434/2019

- Colgan, Beth A. Graduating Economic Sanctions According to Ability to Pay. Iowa Law Review. [Online] 103(53) 2017. https://ilr.law.uiowa.edu/print/volume-103-issue-1/graduating-economic-sanctions-according-to-ability-to-pay/

- Bureau of Justice Assistance. How to Use Structure Fines (Day Fines) as an Intermediate Sanction. U.S. Department of Justice. [Online] November 1996. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles/156242.pdf

- Kantorowicz-Reznichenko, Elena. Day Fines: Reviving the Idea and Reversing the (Costly) Punitive Trend. Georgetown Law’s American Criminal Law Review (Vol. 55, Iss. 2). [Online] 2018. https://www.law.georgetown.edu/american-criminal-law-review/in-print/volume-55-number-2-spring-2018/day-fines-reviving-the-idea-and-reversing-the-costly-punitive-trend/

- Zedlewski, Edwin W. Alternatives to Custodial Supervision: The Day Fine. National Institute of Justice. [Online] April 2010. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/230401.pdf