Fees and fines are a central part of Tennessee’s criminal justice system – both to punish criminal acts and to fund a basic government function. However, they can also have unintended side effects that make it harder for some people to be productive and contributing members of their communities. This report outlines in broad terms numerous ways that policymakers could seek to better understand and address these challenges. Future reports will examine some of the topics discussed here in more detail.

Two prior reports looked at the different types of fees and fines people can accrue in Tennessee and their impact on different stakeholders, as well as the amount of revenue they raise each year for our state and local governments.

Key Takeaways

- A lack of robust data and varied policies/practices across Tennessee obscure many aspects of criminal justice fees and fines. However, policymakers have many options to consider.

- To start, lawmakers could require state and local officials to report more information on what they charge and why, to whom debts are owed, and how any funds they collect are spent.

- Officials could also jail fewer people before trial, push alternatives to incarceration, and pay more of the costs of holding and monitoring inmates and those on community supervision.

- Governments may want to streamline laws that authorize fees and fines, create more uniformity in how courts weigh a person’s ability to pay, and put more limits on civil asset forfeiture.

- Other options include revising collection practices and payment prioritization and addressing the criminal and financial consequences of unpaid debts.

Background on Fees and Fines

Governments at all levels need money to fund public safety, necessary infrastructure, and other basic services. Compared to other major sources of revenue, criminal fees and fines play a relatively small role in funding state and local government in Tennessee. Even so, national trends have shown that governments’ dependency on fees and fines has grown over the last several decades. (1)

Starting in the 1980s, the number of people in state and local criminal justice systems in the U.S. grew significantly – raising incarceration, court, and public safety costs. (2) (1) (3) With limited budgets and the public generally averse to higher taxes, lawmakers across the country began to shift some of this financial burden to people charged with crimes. (4) (5) This cost shift fit a broader trend toward raising revenue through user fees and charges rather than tax increases. (6) Tennessee alone has passed at least 46 laws since 2005 to either increase existing fees and fines or create new ones. (7) Some of these laws apply statewide, while others affect only certain parts of the state.

While the potential for policy change exists at many levels of government, state law dictates most of the criminal fees and fines in Tennessee. For example, recent research found that state law authorized about three quarters of fees and fines collected in Davidson County. (8) However, Davidson County has also recently eliminated daily jail fees for inmates, declined to prosecute certain minor offenses, and stopped prosecuting people whose driver licenses are suspended for non-payment of criminal fines and fees. (5) (9) (10)

Key Trade-Offs and Themes of Current Practices

Policymakers who want to change the state’s fee and fine practices without creating new unintended consequences should understand the current system’s key trade-offs and themes.

Fees and Fines Are a Small Portion of Local Revenues

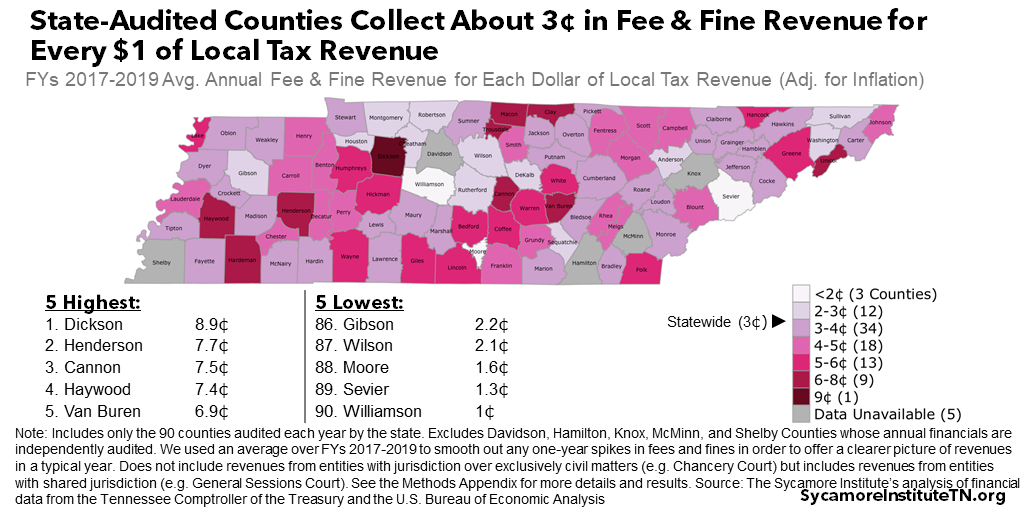

Legal financial obligations (LFOs) represent a relatively small share of most Tennessee counties’ total revenues (Figure 1). Our state and local governments rely far more heavily on taxes than fees and fines when generating money to balance their budgets. For every dollar collected in taxes, three quarters of the state-audited counties raised 5¢ or less from fees and fines. None raised more than 9¢. We found similar trends for Tennessee’s four most populated counties, whose budgets undergo independent audits.

Figure 1

Fees and Fines Don’t Always Pay Off

Fees and fines are often an unreliable revenue stream and in some places even make criminal justice more expensive. (13) (7) LFOs can prolong a person’s time in the system and result in more people behind bars, which may turn into a net cost. Meanwhile, a majority of criminal fees and fines go uncollected, at least in part because many people who owe them do not have a lot of money. (1) (13) Time and resources spent trying to collect unpaid debt can also become a drain on local budgets. (5) While research is limited, tying fee and fine assessments to one’s ability to pay may boost revenues in the long run. (5) (14)

Unequal Debts to Society

For two people with identical offenses, fees, and fines, the one with less money may ultimately pay a much larger debt to society. (15) (1) With standardized fees and fines, the poor may have a harder time than the wealthy paying off criminal justice debts. Failure or inability to pay can prolong a person’s involvement in the criminal justice system, prevent them from having their record cleared, and lead to late fees, surcharges, and even incarceration or other criminal penalties. (2) (7) (16) As a result, people with fewer financial resources may have a harder time leaving the criminal justice system behind and moving on with their lives.

Hard to Evaluate and Conduct Oversight

The structure of Tennessee’s court system makes it hard to know the full impact of fees and fines or to apply a standard, statewide approach. Tennessee’s court system is a mix of state and local courts. (17) The state has 31 judicial districts that hear criminal trials, but each county also has its own courts of limited jurisdiction that hear criminal cases. (7) This results in overlapping authorities, funding sources, and reporting systems. Tennessee’s network of courts also complicates efforts to collect and analyze comparable data on court activities, assess the overall impact of the state’s criminal justice system, and standardize court practices. (7) (17)

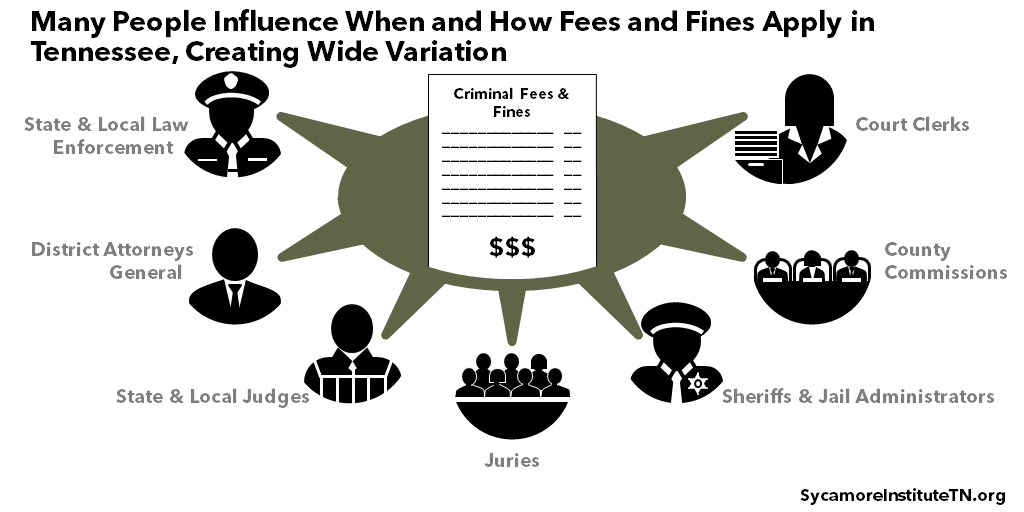

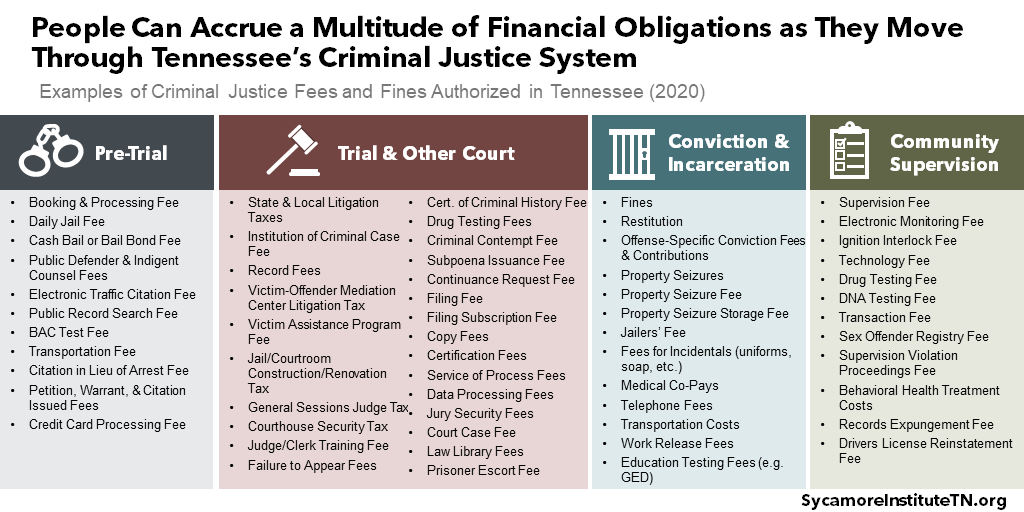

Tennessee’s complex system of fees and fines and the many actors that determine them also make it tough to evaluate. People can face fees and fines at each stage of their interaction with the criminal justice system, and many different actors influence what someone ultimately owes (Figure 2). (8) (18) Prior research found wide inconsistencies in fee and fine assessments across the state. (17) These complexities and a lack of available data make it difficult to get a handle on the typical amount people can expect to owe for any given crime, how that varies from court to court, and whether similar crimes incur similar penalties.

Figure 2

Prioritizing Revenue

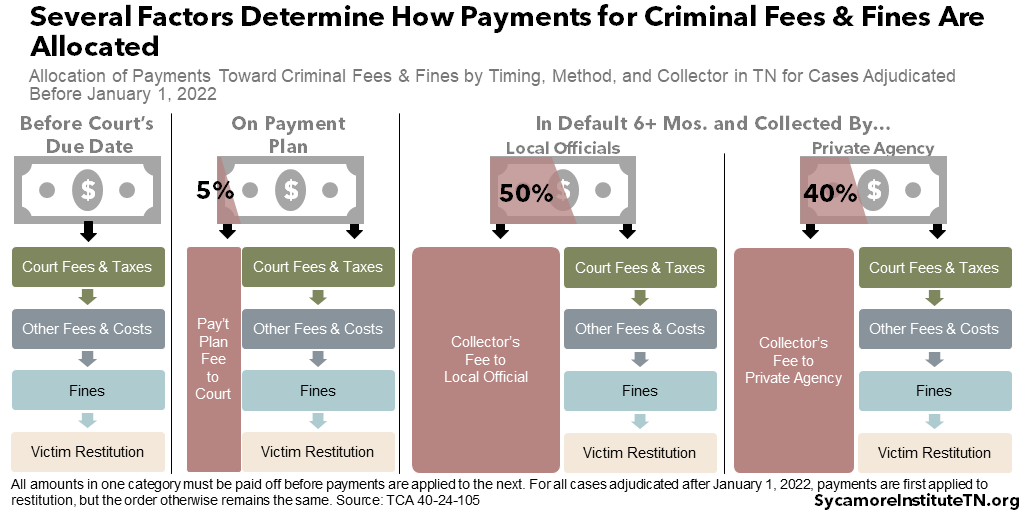

Tennessee explicitly prioritizes the payment of LFOs that raise revenue over punishment for crimes committed. Tennessee law stipulates the order in which payments toward their court fees and fines apply. (19) (44) The money goes to pay off user fees, litigation taxes, and court or incarceration costs before applying to fines levied as punishment for a criminal conviction.

Relying on fees and fines to help fund the criminal justice system can also incentivize public officials in undesirable ways. (2) (1) (8) For example, these pressures can lead local governments to focus on law enforcement activities that maximize revenue over public safety. Other research has shown this can damage public trust, which has its own long-term consequences. (20) Researchers have repeatedly identified concerns about civil asset forfeiture, for example, which requires a low burden of proof to confiscate private property. (21) (22) In Tennessee, law enforcement agencies generally get to keep all of the proceeds from these seizures. (21)

11 Potential Avenues for Reform in Tennessee

State lawmakers who want to address any downsides of criminal justice fees and fines have many policy levers available. Tennessee law creates the framework for which fees and fines can apply in any particular situation, as well as who can assess them. While not an exhaustive list, the items summarized below represent a wide range of potential avenues to explore. In future reports, Sycamore will examine some of these topics at greater length – including a closer look at Tennessee’s practices and an exploration of trade-offs and other key considerations.

More and Better Information

Fully understanding the use and impact of LFOs across Tennessee will require much more robust data. Much remains unknown about fees and fines as a revenue source in Tennessee and the effect on residents who owe them. Existing assessment and collection studies give point-in-time estimates only. Our recent analysis is the first to use audited financial data to examine LFOs as a local funding source statewide, but it has limitations as well (e.g. includes some civil costs, covers a relatively short time period). Meanwhile, we are not aware of any comprehensive studies of how Tennessee’s fees and fines affect the people who owe them or our criminal justice system. Gathering this data may be difficult due to the state’s court structure and the number of stakeholders involved, but policymakers may still find it worthwhile.

Figure 3

Comprehensive Review with Cross-Stakeholder Engagement

Tennessee laws that govern criminal fees and fines create a complex web of rules. The state code authorizes over 360 LFOs spread across 17 titles and over 50 chapters (Figure 3). (18) There is wide variation in who can levy fees and fines, how they are collected, and what they fund. Along with our decentralized court system, these factors make it hard to evaluate if fees and fines serve their intended purpose. In light of this, policymakers took steps in 2005 to simplify state laws related to court fees. (7) However, lawmakers have since added dozens of statutes authorizing new fees and fines. Legislators could build on the 2005 effort by expanding the scope of reforms to include all LFOs authorized by state law. A comprehensive review would help policymakers answer questions like:

- Do the fees and fines authorized by state law reflect policymakers’ goals?

- Are comparable crimes subject to comparable fees and fines?

- Are there redundancies in state code that could be simplified, combined, or amended?

Effective policy changes may require coordination between various stakeholders that influence legal financial obligations. The characters in this cast (Figure 2) often operate independently and have their own goals and incentives. Understanding each actor’s motivations and concerns could smooth the approach to either incremental or wholesale reform.

Ability to Pay

Policymakers could create more uniformity in how courts weigh a person’s ability to pay fees and fines. State law provides a framework – called indigency waivers – that lets a court waive fees and fines for people with limited economic means. (23) (7) (24) However, applying for indigency status is rarely straightforward. Heavy caseloads and limited resources can also create a lot of variation in how much time courts spend evaluating a person’s ability to pay. (25) (23) (7) This can lead to people owing fees and fines they cannot afford and governments using up resources in an attempt to collect bad debt. Examples of alternative approaches include:

- Standardized criteria for determining indigency status.

- Providing funds to ease the local burden of carrying out ability-to-pay hearings.

- Statewide reporting on the use of indigency waivers across Tennessee. (15)

- Automatic calculation of fines based on both the severity of an offense and a defendant’s income. (14)

Streamlined Fees and Taxes

Lawmakers could continue previous efforts to standardize the fees and taxes in state law. Tennessee law currently authorizes over 360 different LFOs (Figure 3) related to criminal proceedings. (18) (7) Most apply statewide, while others are limited to certain localities. Many also have complex formulas for distributing the revenue collected. As a result, it can be difficult to gauge how much a person could owe, to whom, and where the money ultimately goes. State lawmakers took steps in this direction by creating a standard, centralized court fee system in 2005. (7) Additional simplification could give stakeholders a better sense of how costs can accumulate for individuals, whether or not current practices merit reform, and what this money funds. (7)

Order of Payments

Policymakers may want to consider how payments apply to multiple LFO debts and whether that order reflects their goals for criminal justice fees and fines. Legal financial obligations serve many purposes – to fund the criminal justice system, to punish criminality, and to make victims whole. Until January 1, 2022, state law effectively prioritizes these purposes by requiring all revenue-generating obligations to be paid off before punitive fines or restitution (Figure 4). For cases adjudicated after that date, payments will go towards restitution first, but the order otherwise remains the same. (44) Policymakers could apply these changes retroactively to existing debts and/or make fines a higher priority.

Figure 4

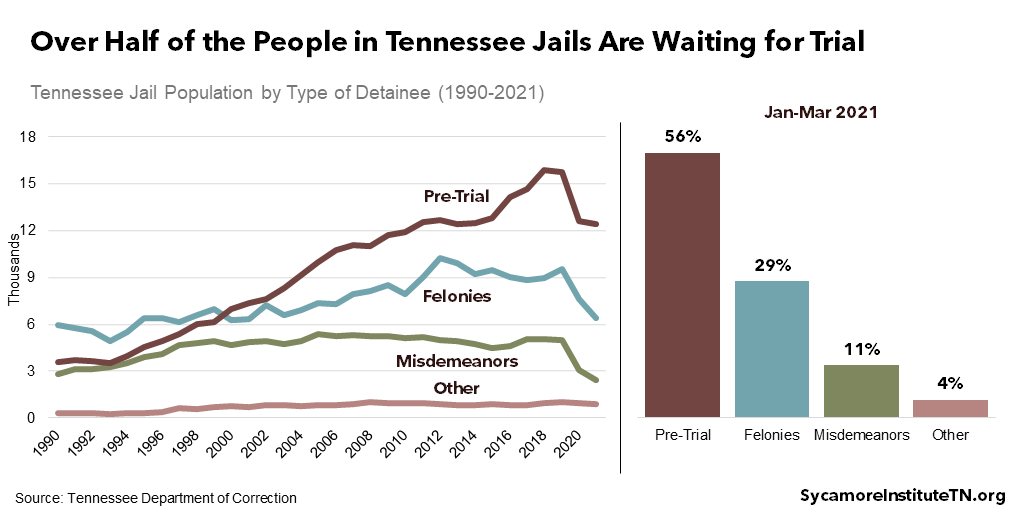

Pre-Trial Release

Policymakers could consider ways that allow for more pre-trial release without bail while still ensuring public safety. Through the first several months of 2021, 56% of all local jail inmates in Tennessee were pre-trial detainees (Figure 5). (27) Nationwide, judges increasingly require money bail – and rising amounts – before releasing defendants from state custody ahead of trial. (4) (28) Defendants who remain in jail because they cannot afford bail may lose their jobs/income or find it harder to get a job after release. (2) (29) In Tennessee, judges have wide discretion over when and how high to set bail, but lawmakers can influence the process as well. (30) For example, a handful of Tennessee counties have implemented validated risk assessment tools to help courts decide about pre-trial release. (31) Meanwhile, several jurisdictions elsewhere have seen jail populations and operating costs fall after eliminating money bail – without a significant drop in people appearing for trial. (32) (33)

Figure 5

Alternatives to Incarceration

More emphasis on alternatives to incarceration for low-level offenders might reduce costs for both individuals and government. Recent national data show the typical jail inmate spends about 25 days behind bars. (34) Most people in jail are there for minor offenses, and jail time is typically too short for meaningful rehabilitation. (8) However, it can last long enough to lose a job and fall behind on bills. To prevent this, state lawmakers could consider more policies that let people serve their sentences through community service programs that incorporate vocational training. For example, lawmakers recently expanded access to drug treatment diversions and community corrections for certain types of offenders. (35) (36)

Service Charges

Policymakers could pick up more of the costs related to holding and monitoring inmates and those on community supervision. State law permits jails and prisons to charge inmates for things like housing, uniforms, and basic hygienic supplies. (37) (38) Officials can also charge fees for community supervision, electronic monitoring, and drug testing. (39) (40) Together, these costs can become debts that make it harder for people getting out of the system to get back on their feet. Partially or fully funding some or all of these services could reduce individuals’ financial stress and help them become more productive citizens.

Criminal and Financial Consequences of Unpaid Debts

Unpaid fees and fines often generate direct criminal penalties and other, indirect costs. Failure to make timely payments on criminal justice debt can lead to more court fees, garnished wages, property liens, and extended probation. (7) Tennesseans with unpaid LFOs are also ineligible to have prior convictions expunged from their records. (16) Meanwhile, indirect costs of going to court for unpaid debts may include missing work and finding and paying for transportation and child care. (8) In some cases, nonpayment can result in a suspended driver’s license or even re-incarceration. (23) Jailing someone for unpaid debts without first showing they are able to pay violates the U.S. Constitution. (41) However, Tennessee courts can incarcerate people for nonpayment of criminal fines and fees if a judge determines they are not indigent. (7) As noted above, that decision may vary from one court to another.

These additional penalties and costs may actually reduce the amount of fee and fine revenue that courts and agencies ultimately collect. Suspending people’s licenses, for example, can make it harder for individuals to earn a living and thereby pay down their debts. Meanwhile, debts that feel insurmountable can lead a person to stop even trying to repay. (42) (13) (14) Policymakers could consider enacting provisions that mitigate any or all of these policies (e.g. license suspension, additional monetary penalties, re-incarceration, etc.) to make getting payments back on track easier. (43) Steps like these could potentially boost collection rates and lower costs for government while easing the path to reintegration and productivity for Tennesseans with criminal justice debt.

Debt Collection Practices

Lawmakers could make court debts easier to pay off by revising collection policies. As with any unpaid debt (i.e. credit cards, car loans), collection proceedings can start once an LFO is in default for six months. At this point, state law allows agencies that collect any future payments to keep 40-50% as a finder’s fee – meaning the debt could effectively double and take twice as long to repay (Figure 4). (19) In addition, state law gives local governments little guidance on how to set payment plans or collect debts that are in default. Some changes that policymakers might consider include:

- Smaller finder’s fees when collecting LFOs in default.

- More transparency and data collection on how local officials approve payment plans and reductions for defaulted debt.

- Minimum standards for the procedures public and private agencies can use to collect defaulted debt.

Asset Forfeiture

Policymakers could put more limits on the use of civil asset forfeiture. Law enforcement agencies can seize assets through either civil or criminal forfeiture. (21) While criminal forfeitures require a criminal conviction, civil forfeitures have a much lower standard of proof. In fact, law enforcement can use it to seize a person’s property without ever charging them with a crime. Tennessee passed laws in 2013 that outlined stronger protections for property owners and in 2016 that increased reporting requirements. (21) State lawmakers could also consider changes that reduce or eliminate fees for contesting a seizure in court, restrict the situations in which civil asset forfeiture is allowed, or increase the burden of proof required for civil asset forfeiture.

Parting Words

Fees and fines play a major role in Tennessee’s criminal justice system, serving as both a source of funding and a form of punishment. Unfortunately, many elements of state law can make it hard for people convicted of crimes to both pay their debts to and reintegrate with society – especially if they have little money. Policymakers who want to mitigate these challenges have a wide range of options. As a starting point, there is an urgent need for better data on what people are charged, how those amounts get decided, to whom these debts are owed, and how any funds collected are spent.

* This report was updated on July 9, 2021 to reflect recent legislative changes to payment prioritization.

References

Click to Open/Close

- Martin, Karin D., Smith, Sandra Susan and Still, Wendy. Shackled to Debt: Criminal Justice Financial Obligations and the Barriers to Re-Entry They Create. New Thinking in Community Corrections. [Online] January 17, 2017. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/249976.pdf

- Liu, Patrick, Nunn, Ryan and Shambaugh, Jay. Nine Facts About Monetary Sanctions in the Criminal Justice System. The Hamilton Project. [Online] March 15, 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/BailFacts_20190314.pdf

- Pellegrin, Mandy. Incarceration in Tennessee: Who, Where, Why, and How Long? The Sycamore Institute. [Online] February 14, 2019. https://www.sycamoreinstitutetn.org/incarceration-tn-prisoner-trends/

- U.S. Council of Economic Advisers. Fines, Fees, and Bail: Payments in the Criminal Justice System That Disproportionately Impact the Poor. National Institute of Corrections. [Online] December 2015. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/page/files/1215_cea_fine_fee_bail_issue_brief.pdf

- Worthington, Paula R. Best Practices: Reforming Fine & Fee Policies in the Criminal Justice System. PFM Center for Justice & Safety Finance. [Online] August 2020. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f0735ceb487f10af7ea8372/t/5f3bfc5eb7b82234a999fd4e/1597766750639/Fines+and+Fees+Best+Practices_August+2020_Harris+Center.pdf

- Miller, Girard. Fines, Fees, Forfeitures and the Emerging Issue of Fairness. Governing. [Online] December 8, 2020. https://www.governing.com/finance/Fines-Fees-Forfeitures-and-the-Emerging-Issue-of-Fairness.html

- Barrie, Jennifer, et al. Tennessee’s Court Fees and Taxes: Funding the Courts Fairly. Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations (TACIR). [Online] January 26, 2017. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tacir/documents/2017_CourtFees.pdf

- PFM Center for Justice & Safety Finance. Reducing Reliance on Fines & Fees. Metro Government of Nashville & Davidson County, Tennessee. [Online] 2020 October. https://www.nashville.gov/Portals/0/SiteContent/MayorsOffice/docs/news/Cooper/FinesFeesReport.pdf

- Timms, Mariah. Nashville DA to Stop Prosecuting Minor Marijuana Possession Offenses Immediately. The Tennessean. [Online] July 1, 2020. https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/crime/2020/07/01/nashville-da-no-more-minor-marijuana-possession-prosecutions/5356627002/

- Tamburin, Adam. Prosecutor’s New Plan for Driver’s License Violations Could Keep 12,000 Cases Out of Court. The Tennessean. [Online] September 4, 2018. https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/crime/2018/09/04/drivers-license-violations-nashville-glenn-funk-steering-clear/1161034002/

- Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury. Local Government Audit. Transparency and Accountability for Governments. [Online] November 2020. https://apps.cot.tn.gov/TAG/

- U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Table 1.1.4. Price Indexes for Gross Domestic Product. Interactive Data: National Income and Product Accounts. [Online] November 2020. https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=19&step=3&isuri=1&select_all_years=0&nipa_table_list=4&series=a&first_year=2007&last_year=2019&scale=-99&categories=survey&thetable=

- Menendez, Matthew and Eisen, Lauren-Brooke. The Steep Costs of Criminal Justice Fees and Fines. The Brennan Center. [Online] November 21, 2019. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/steep-costs-criminal-justice-fees-and-fines

- Colgan, Beth A. Graduating Economic Sanctions According to Ability to Pay. Iowa Law Review. [Online] 103(53) 2017. https://ilr.law.uiowa.edu/print/volume-103-issue-1/graduating-economic-sanctions-according-to-ability-to-pay/

- Criminal Justice Policy Program. Confronting Criminal Justice Debt: A Guide for Policy Reform. Harvard Law School. [Online] September 2016. http://cjpp.law.harvard.edu/assets/Confronting-Crim-Justice-Debt-Guide-to-Policy-Reform-FINAL.pdf

- Tennessee District Public Defenders Conference. Tennessee Expunction Eligibility. [Online] https://www.tn.gov/expunction/eligibility.html

- Morgan, John G., Denton, Denise and Adamson, Bonnie S. Tennessee’s Court System: Is Reform Needed? Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury. [Online] January 30, 2004. https://comptroller.tn.gov/content/dam/cot/orea/documents/orea-reports-2004/2004_OREA_CourtReform.pdf

- Tuggle, Bryce. Fees, Fines, and Criminal Justice in Tennessee: How it All Works and Why it Matters. The Sycamore Institute. [Online] December 22, 2020. https://www.sycamoreinstitutetn.org/fees-fines-and-criminal-justice-in-tennessee/

- State of Tennessee. Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-24-105: Collection of Fines, Costs and Litigationn Taxes – Installment Payment Plan – Suspended License – Restricted License – Conversion to Civil Judgment – Settlement. [Online] https://law.justia.com/codes/tennessee/2019/title-40/chapter-24/section-40-24-105/

- Carpenter II, Dick M., Sweetland, Kyle and McDonald, Jennifer. The Price of Taxation by Citation: Case Studies of Three Georgia Cities that Rely Heavily on Fines and Fees. Institute for Justice. [Online] October 2019. https://ij.org/report/the-price-of-taxation-by-citation/

- Tennessee Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. The Civil Rights Implications of Tennessee’s Civil Asset Forfeiture Laws and Practices. U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. [Online] February 14, 2018. https://www.usccr.gov/pubs/2018/09-12-TN-Civil-Laws.pdf

- Knepper, Lisa, et al. Policing for Profit: The Abuse of Civil Asset Forfeiture – 3rd Edition. Institute for Justice. [Online] December 2020. https://ij.org/wp-content/themes/ijorg/images/pfp3/policing-for-profit-3-web.pdf

- Tennessee Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Legal Financial Obligations in the Tennessee Criminal Justice System. U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. [Online] January 15, 2020. https://www.usccr.gov/pubs/2020/01-15-TN-LFO-Report.pdf

- Tennessee Supreme Court. Rule 29: Uniform Civil Affidavit of Indigency. [Online] https://www.tncourts.gov/rules/supreme-court/29

- Indigent Representation Task Force. Liberty & Justice for All: Providing Right to Counsel Services in Tennessee. Tennessee Supreme Court. [Online] April 2017. http://www.tncourts.gov/sites/default/files/docs/irtfreportfinal.pdf

- State of Tennessee. Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-24-105: Collection fo Fines, Costs and Litigation Taxes – Installment Payment Plan – Suspended License – Restricted License – Conversion to Civil Judgment – Settlement. [Online] https://law.justia.com/codes/tennessee/2019/title-40/chapter-24/section-40-24-105/

- Tennessee Department of Correction. Tennessee Jail Summary Reports (1996-2021) . [Online] https://www.tn.gov/correction/statistics-and-information/jail-summary-reports.html

- Liu, Patrick, Nunn, Ryan and Shambaugh, Jay. The Economics of Bail and Pretrial Detention. The Hamilton Project. [Online] December 31, 2018. https://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/files/BailFineReform_EA_121818_6PM.pdf

- Satterfield, Jamie. Tennessee Judges are Brushing Aside Bail Laws, and It’s Costing You. Knoxville News Sentinel. [Online] February 23, 2021. https://www.tennessean.com/in-depth/news/crime/2021/02/23/tennessee-judges-ignoring-bail-laws-and-its-costing-you/4436704001/

- State of Tennessee. Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-11-118: Execution and Deposit – Bail Set No Higher Than Necessary – Factors Considered – Bonds and Sureties. [Online] https://law.justia.com/codes/tennessee/2019/title-40/chapter-11/part-1/section-40-11-118/

- Warren, Julie. To Protect Public Safety, Pretrial Release Must Turn on Risk. Right on Crime. [Online] February 26, 2021. https://rightoncrime.com/2021/02/to-protect-public-safety-pretrial-release-must-turn-on-risk/

- Weekend Edition. What Changed After D.C. Ended Cash Bail. NPR. [Online] September 2, 2018. https://www.npr.org/2018/09/02/644085158/what-changed-after-d-c-ended-cash-bail

- Hernandez, Joe. N.J. Officials Finally Release Data on Bail Reform. Their Conclusion? It’s Working. NPR. [Online] April 2, 2019. https://whyy.org/articles/n-j-officials-have-finally-released-data-on-bail-reform-their-conclusion-its-working/

- Zheng, Zhen. Jail Inmates in 2018. U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Online] March 31, 2020. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ji18.pdf

- 112th General Assembly. HB0784/SB0767. Tennessee General Assembly. [Online] 2021. https://wapp.capitol.tn.gov/apps/BillInfo/Default.aspx?BillNumber=SB0767&GA=112

- Allison, Natalie. Gov. Bill Lee is as Close as Ever to Passing Criminal Justice Reform. Here’s What He’s Doing. The Tennessean. [Online] April 7, 2021. https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/politics/2021/04/08/tennessee-criminal-justice-reform-bill-lee-pushes-diversion-reentry-plan/7121586002/

- State of Tennessee. Tenn. Code Ann. § 41-11-101/12. Inmate Reimbursement to the County Act of 1995. [Online] https://law.justia.com/codes/tennessee/2019/title-41/chapter-11/

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 41-4-142: Charging Inmates for Issued Items. [Online] https://law.justia.com/codes/tennessee/2019/title-41/chapter-4/section-41-4-142/

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-28-201: Parolees, Probationers and Employed Releasees – Contributions Required – Arrearages – Records. [Online] https://law.justia.com/codes/tennessee/2019/title-40/chapter-28/part-2/section-40-28-201/

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 55-10-418: Maximum Allowable Fee – Reports. [Online] https://law.justia.com/codes/tennessee/2019/title-55/chapter-10/part-4/section-55-10-418/

- Holik, Haley and Levin, Marc. Confronting the Burden of Fines and Fees on Fine-Only Offenses in Texas: Recent Reforms and Next Steps. Right on Crime. [Online] April 2019. https://rightoncrime.com/2019/05/confronting-the-burden-of-fines-and-fees-on-fine-only-offenses-in-texas-recent-reforms-and-next-steps/

- Bannon, Alicia, Nagrecha, Mitali and Diller, Rebekah. Criminal Justice Debt: A Barrier to Reentry. The Brennan Center. [Online] October 4, 2010. https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/2019-08/Report_Criminal-Justice-Debt- A-Barrier-Reentry.pdf

- Patel, Roopal and Philip, Meghna. Criminal Justice Debt: A Toolkit for Action. The Brennan Center. [Online] July 10, 2012. https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/2019-08/Report_Criminal Justice Debt.pdf

- State of Tennessee. Public Chapter No. 413 (2021). May 12, 2021. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/112/pub/pc0413.pdf