As communities work to contain the spread of the new coronavirus, the economic toll of the COVID-19 pandemic is getting clearer. This report explores which people, places, and employers in Tennessee this recession has hit hardest to date. It aims to help state and local policymakers grapple with how to mitigate the near-term fallout while hopefully preventing longer-term harm to our economy by slowing the virus’ spread.

Key Takeaways

- One in five Tennessee businesses operated in the most at-risk industries last year: restaurants and bars, sensitive retail and manufacturing, travel and transportation, personal services, and entertainment.

- Those businesses employed one in four private sector workers in our state, a population that earns 40% less than average and is more likely to be minority, young, and have less education.

- Recent surveys affirm that COVID-related job cuts have hit black Tennesseans and the youngest workers disproportionately hard.

- The consequences of joblessness can be significant for financial and emotional well-being, and more industries will likely be affected the longer it takes to control the virus’ spread.

- Policymakers may want to consider issues related to unemployment insurance, digital barriers to assistance, small business viability, personal debt, labor force effects, schools and working parents, loss of job-based health insurance, and mental health.

Acknowledgment: This research was funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. We thank them for their support but acknowledge that the findings and conclusions presented in this report are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Foundation.Sycamore takes a neutral and objective approach to analyze and explain public policy issues. Funders do not determine research findings. More information on our code of ethics is available here.

Near-Term Pain for (Hopefully) Long-Term Gain

The pandemic has created dual public health and economic crises that reinforce each other. Many of the immediate economic consequences were the direct result of steps taken to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus. However, people began to alter their behaviors and spending even before stay-at-home orders took effect, and many will likely continue to do so after those measures end. (1) (2) Just how long these social distancing actions and changes in behavioral patterns will last remains unclear.(3) (4) (5)

Economists generally agree that the longer it takes to halt the pandemic, the more economic damage we are likely to endure. (6) Permanent layoffs are already increasing, even as temporary layoffs have fallen due to many businesses reopening. (7) Policies that effectively manage the pandemic while also addressing the economic fallout may best position the state to minimize the long-term impact of this recession. Davidson County, for example, recently backtracked on its phased reopening and temporarily re-closed bars altogether after a dramatic spike in COVID-19 infections. (8)

Lower Spending and Big Job Losses in the Early Months

Social distancing shut down much of the economy for several months, especially in sectors that pose higher risks for the spread of COVID-19. “Customer-facing” industries were among the most affected, such as food service, transportation, tourism, personal services (e.g. barbers, daycares), retail, entertainment, and recreation. Certain manufacturing sectors that produce goods for these industries (e.g. cars, airplanes) also saw significant disruption. (9) (10) While white collar industries and the public sector have also shed jobs, the ability to telework has dampened losses for some parts of the labor force. (11)

Broad consumer spending plummeted and then largely rebounded, but several sectors have not yet recovered. Private sector data show consumer spending in Tennessee down 26% from January to the end of March before returning more or less to normal in May. As of late July, however, spending remained far below normal in entertainment and recreation (-47%), transportation (-43%), and restaurants and hotels (-17%). Meanwhile, spending on groceries was up 60% in mid-March before settling down to a 10% increase in late July. (12)

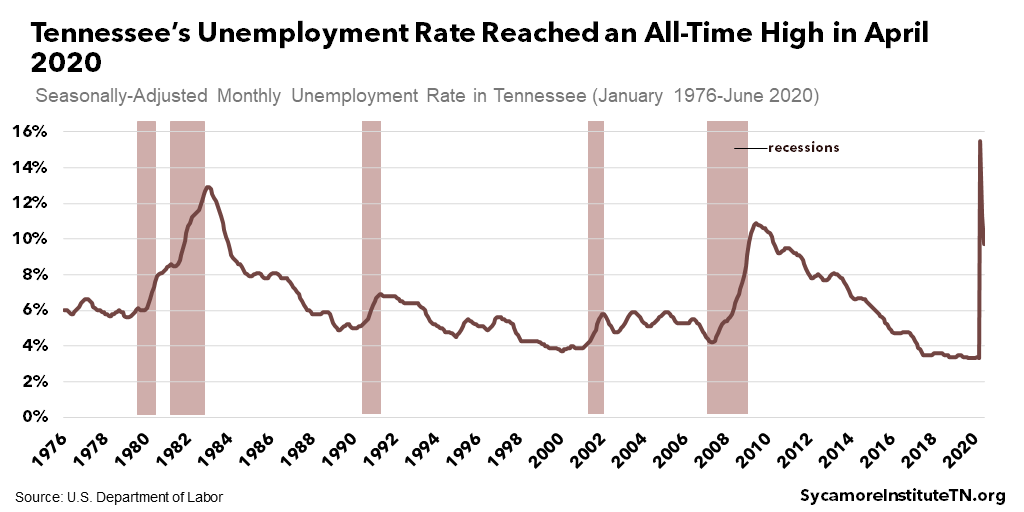

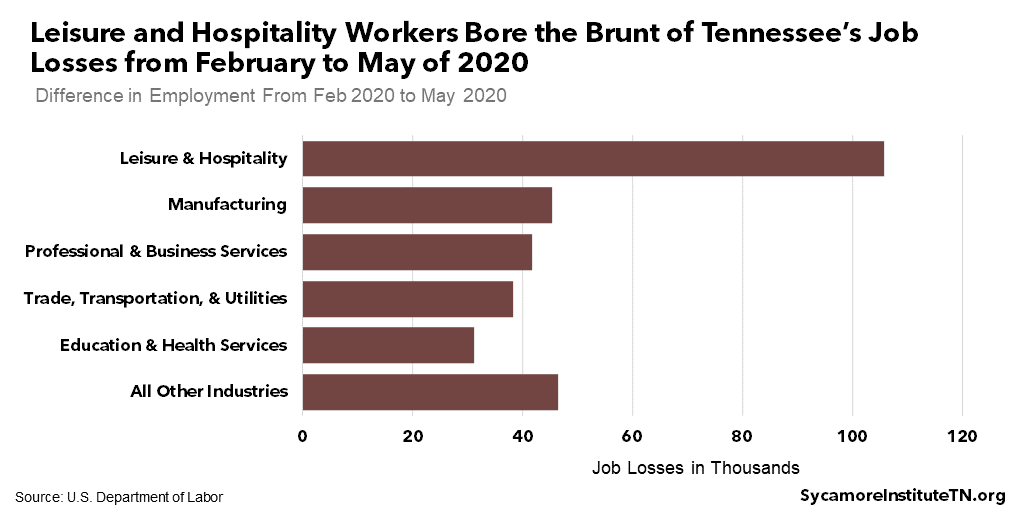

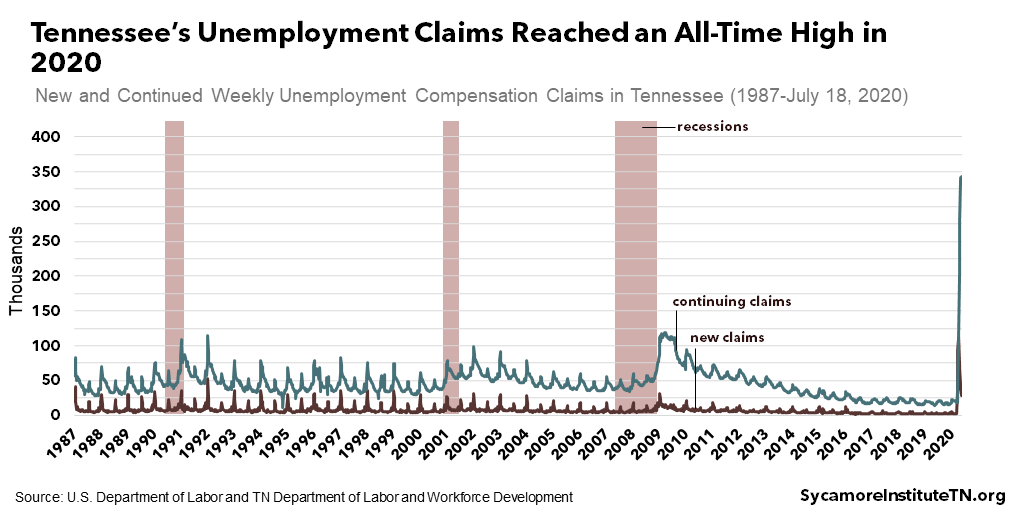

To date, job losses have been concentrated in the industries most affected by social distancing. By June 2020, the official unemployment rate in Tennessee was at 9.7% — down from 14.7% in April, its highest point on record (Figure 1). (13) In a statewide survey conducted by the University of Tennessee in early June, 13% reported losing their job due to COVID-19. (14) These job losses have been largely concentrated in the leisure and hospitality sectors (Figure 2). (15) Meanwhile, continuing claims for unemployment insurance also remain at all-time highs even as new weekly claims dropped below their highest levels (Figure 3). (16) (17)

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

A Closer Look at Tennessee’s Most At-Risk Industries

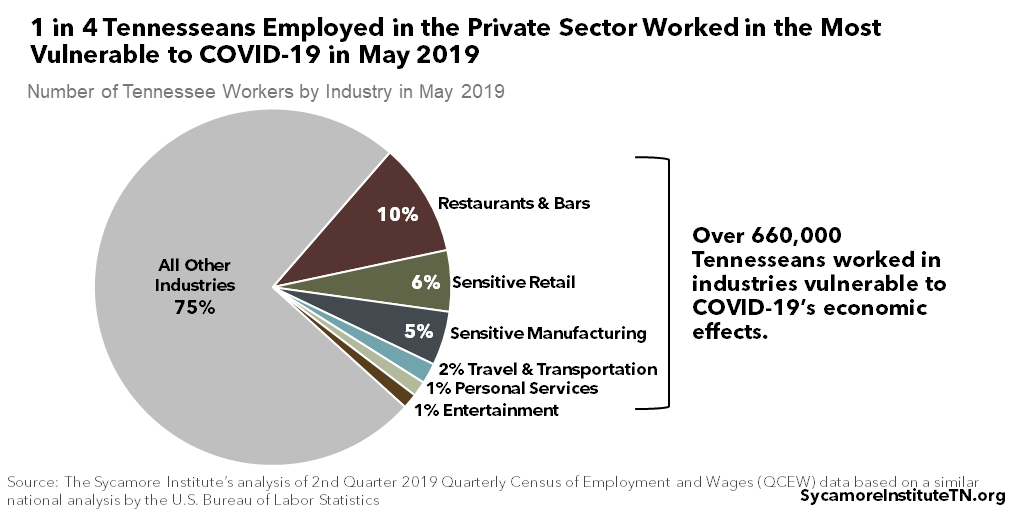

Last year, a little over one in five Tennessee businesses operated in the industries most vulnerable to the economic effects of COVID-19. Across the state, there were about 34,000 of these businesses in April-June of 2019 (Figure 4).

Those businesses employed one in four of our state’s private sector workers, or just over 660,000 people (Figure 5). That is higher than the national rate of about one in five. Restaurants and bars alone accounted for about 10% of Tennessee’s workforce in May 2019. (18) (10)

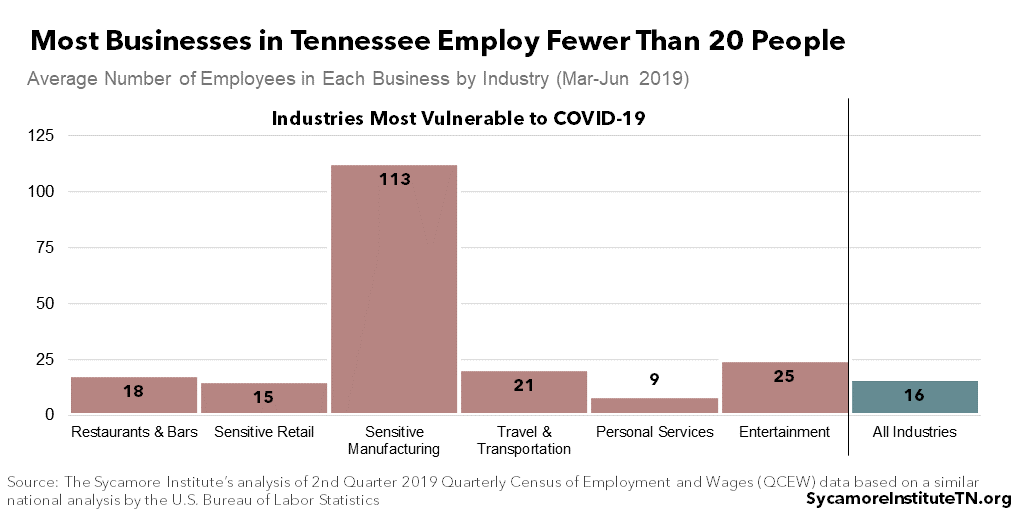

Companies that are both small and front-facing or service-oriented — as well as their employees — may be particularly at risk for job losses during the current pandemic. (19) During the Great Recession, the businesses hit hardest by job losses had fewer than 50 employees. (20) On average, Tennessee businesses across all industries employ fewer than 20 people (Figure 6). (18) A recent nationwide survey of businesses with less than 500 employees found that 14% of respondents expected to lay off workers once federal coronavirus business loans expire. (21)

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

The Geography of Jobs and Businesses Most At-Risk

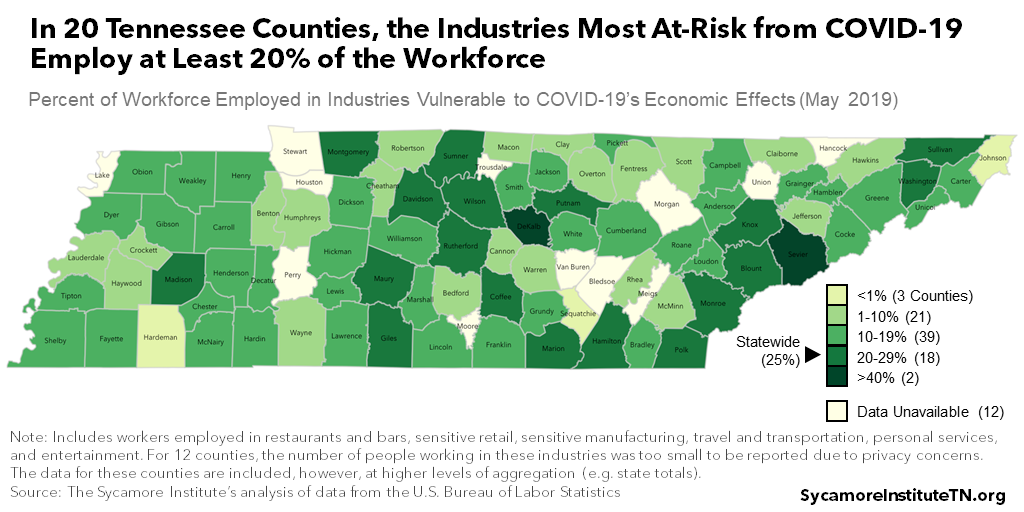

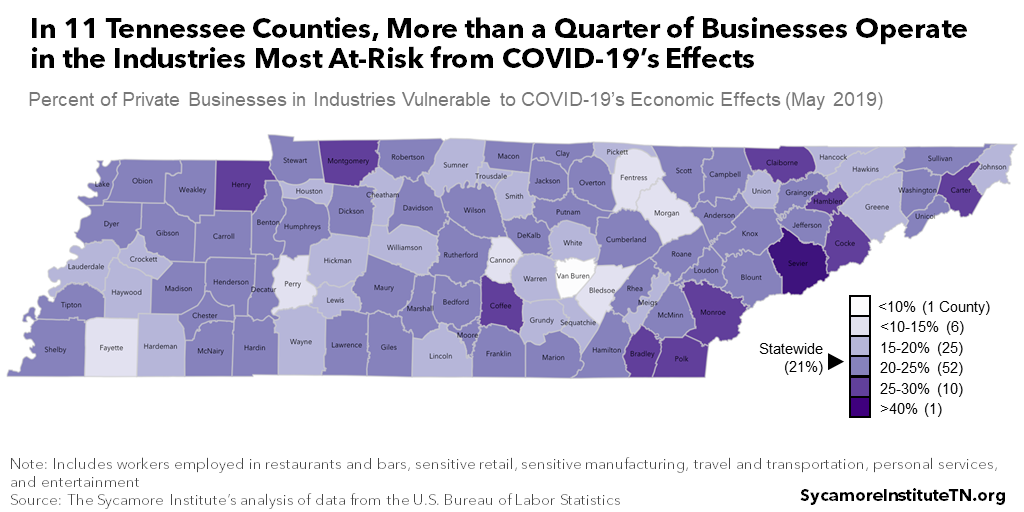

In 20 counties, at least one in five jobs are in the industries most vulnerable to the economic effects of this pandemic. Among the 83 counties with relevant employment data available, the share of jobs in these industries ranged from less than 1% in three counties to just over 60% in Sevier County (Figure 7). (18)* Within counties, the share of all businesses that are in vulnerable industries varies from 6% in Van Buren County to 41% in Sevier County (Figure 8).

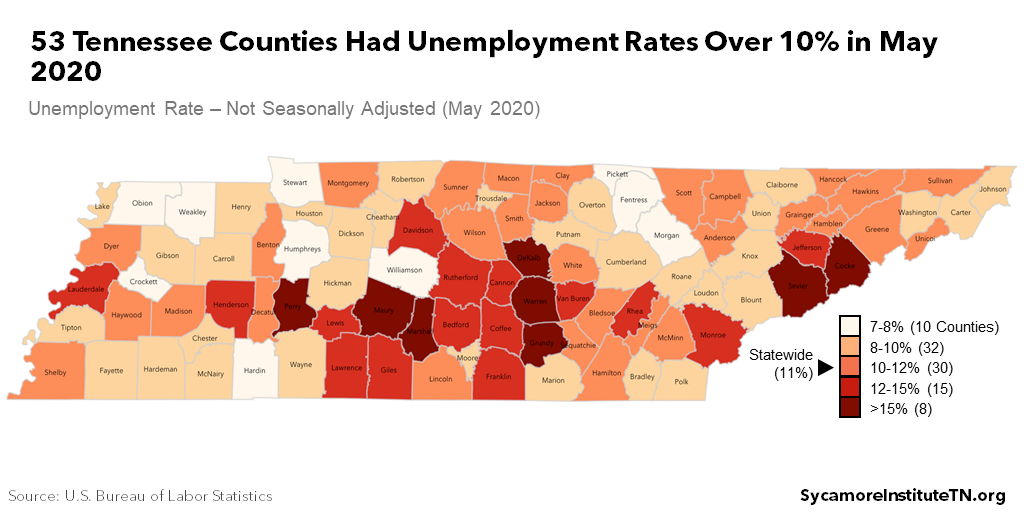

Not surprisingly, counties with relatively more workers in the most affected industries now have some of the highest unemployment rates (Figure 9). In May, the official unemployment rate reached 18.5% in Sevier County, 17.6% in Warren County, and 17.5% in Marshall County. (22) At the highest point in April, 12 counties had unemployment rates of 20% or higher. (23)

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Tennesseans Working in the Most At-Risk Industries

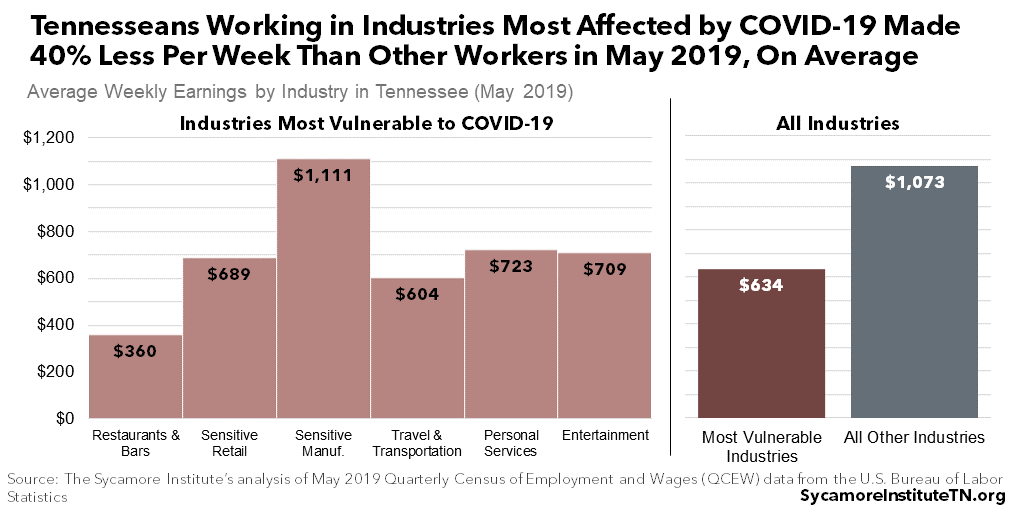

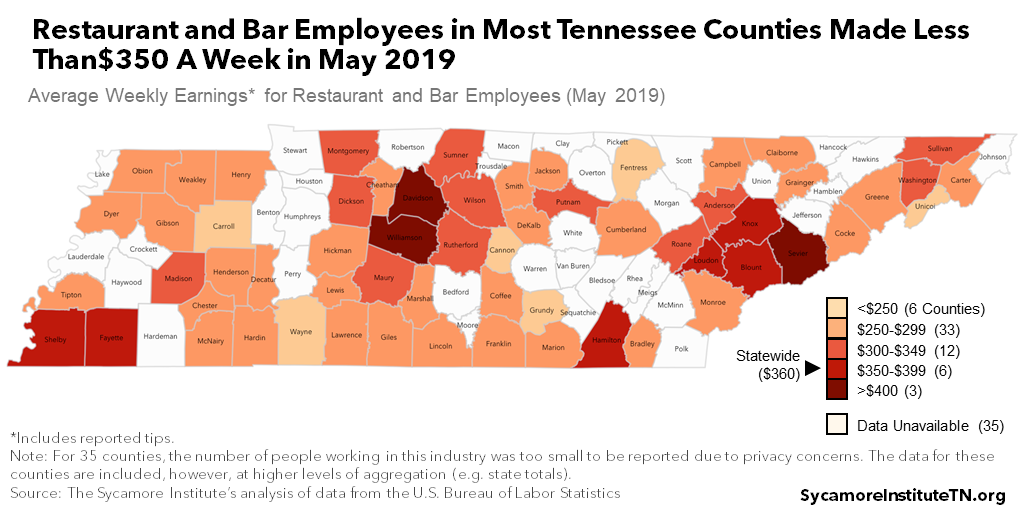

The average Tennessean working in the most at-risk industries earns about 40% less per week than those in other industries (Figure 10). (18) Employees of manufacturers sensitive to COVID-19 made above-average wages in May 2019, but the typical worker in the most vulnerable industries earned much less — due to both lower hourly wages and a higher rate of part-time work. (9) Tennesseans working in restaurants and bars have the lowest average pay of any industry, earning about $360 per week with tips that month — the equivalent of $18,720 per year (Figure 11).

Figure 10

Figure 11

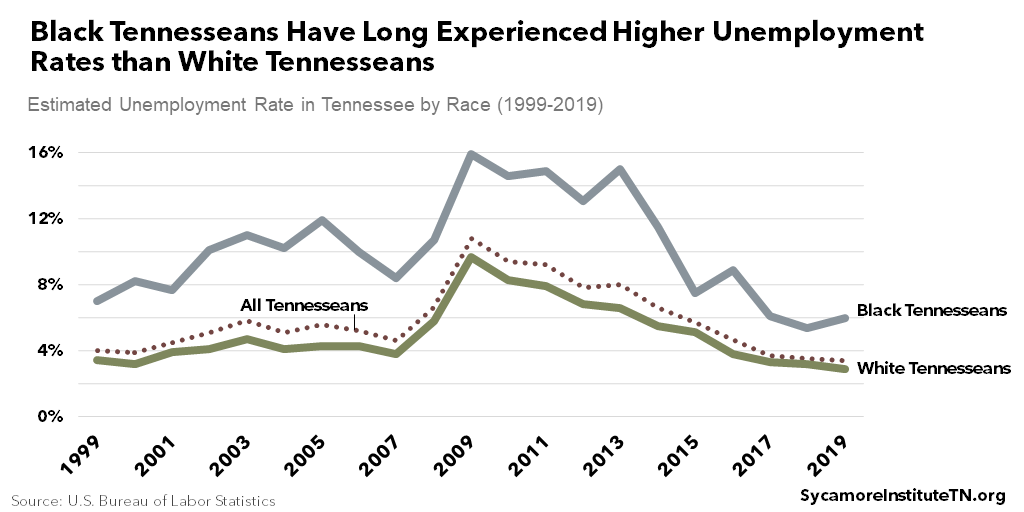

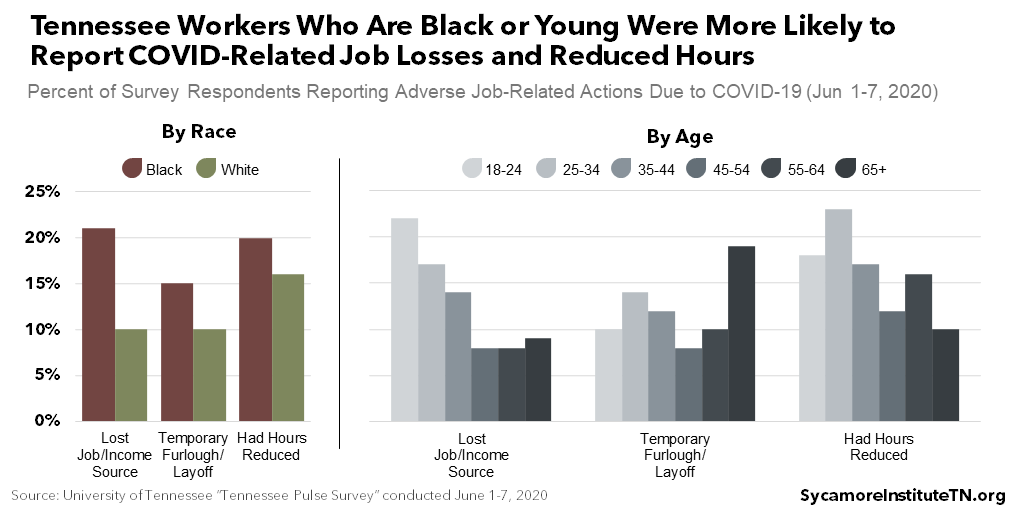

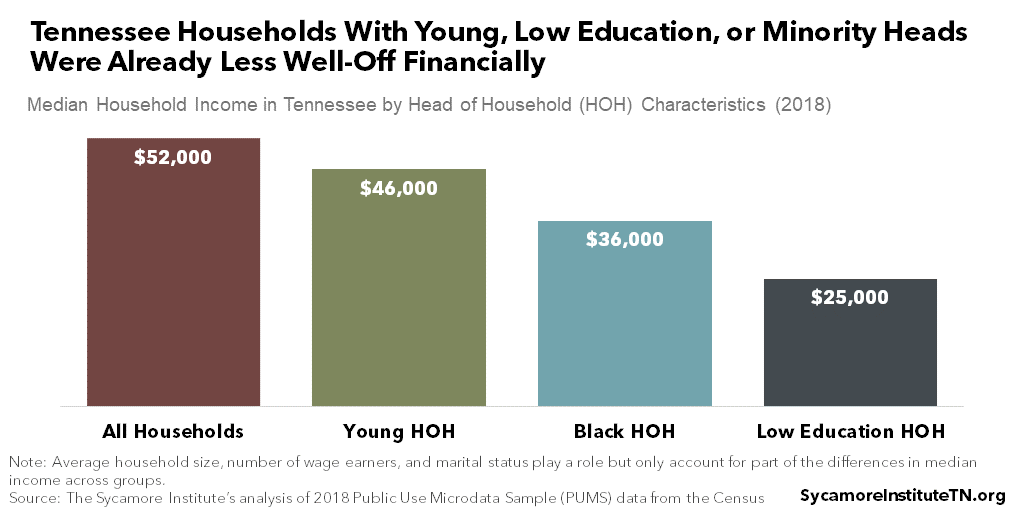

Minorities, young people, and workers with less education and wealth tend to be most affected by job losses during downturns and disproportionately hold jobs in the most at-risk industries. (25) (26) (27) (28) (29) For example, Tennesseans ages 16-24 are by far the most likely to work in industries most affected by social distancing, regardless of education (30). Meanwhile, black Tennesseans have long experienced higher unemployment rates than white Tennesseans — at times twice or even three times higher (Figure 12). (31)

Recent surveys affirm that COVID-related job cuts have hit black Tennesseans and the youngest workers disproportionately hard. A statewide survey the University of Tennessee (UT) conducted in June found black respondents and younger respondents were more likely to report job losses and reduced hours than their counterparts (Figure 13). (14) These results largely echo similar studies that have looked at the nation as a whole. (32)

Figure 12

Figure 13

The Coronavirus Recession’s Broader Economic Fallout

While the pandemic adds an unusual degree of uncertainty, many economists expect unemployment to remain high through at least 2021. (33) (34) The longer it takes to control the virus’ spread, the more temporary layoffs will become permanent and the more job losses and business failures will spread to industries that have to date fared relatively well. (7)

The consequences of joblessness can be significant for financial and emotional well-being. (35) (36) Several studies have shown that the longer people are out of work, the more likely they are to deplete any emergency savings and to accumulate debt. Long-term unemployment is also associated with lowered chances of labor force re-entry, decreased lifetime earnings, and negative effects on physical and mental health. Additionally, studies have shown that joining the labor market during economic downturns can also have long-term consequences for career and earnings potential. (37) (38)

Impact on Tennesseans with the Highest Risk of Early Job Losses

These consequences may be especially acute for the young, minority, lower-income, and less-wealthy Tennesseans who disproportionately work in the most at-risk industries. (14) The populations working in especially vulnerable industries not only have less money to save, they also tend to have fewer resources to draw upon during unexpected periods of unemployment. This can leave them less prepared to weather financial shocks. (39) Minority, lower education, and younger households tend to have lower incomes and less overall wealth than their respective counterparts — gaps only partly explained by differences in household size, number of wage earners, and marital status (Figure 14). (40) (41) (30)

The statewide UT survey conducted in June also suggest that black Tennesseans may be experiencing the economic fallout of COVID-19 more acutely than white Tennesseans — results that are consistent with similar national surveys. (14) (32) Among the findings:

- Of those working, 61% of black respondents and 27% of white respondents were “extremely” or “very” concerned about their ability to keep their jobs.

- 57% of black respondents and 36% of white respondents said they were “extremely” or “very” concerned about their ability to buy necessities like food, medicine, and hygiene products.

- 19% of black respondents and 14% of white respondents reported that they’ve already or will soon miss a bill payment.

- 15% of black respondents and 7% of white respondents said they’ve missed or will soon miss paying their mortgage or rent. (14)

Figure 14

Impact on All Tennesseans

More industries will likely be affected the longer it takes to slow the spread of the new coronavirus. (42) Although jobs began to rebound in May due to easing of restrictions around the country, many communities have since brought restrictions back in the face of sharp spikes in caseloads. (43) (44) This tension highlights the tightrope policymakers face as they attempt to prevent new outbreaks of COVID-19 while allowing people to return to work.

Job losses and pay cuts could also add further stress to Tennessee’s already above-average rates of debt delinquency. (45) In 2018, 37% of Tennesseans with a credit report had some form of past-due debt on their record — versus 31% nationally. Across the state, that figure ranged from 14% in Williamson County to just under 60% in Lake County (Figure 15). (45) In late 2019, an estimated 13% of Tennesseans were delinquent on a student loan, 8% on credit card debt, and 5% on a car loan. (46) Even small amounts of unwanted debt can hinder economic security by feeding debt cycles and reducing access to jobs, housing, and forms of credit that help build wealth.

Rising household debt can become a long-term drag on the economy. While rising consumer debt can be a sign of high consumer confidence and GDP growth, it can also be a negative omen if driven by spending on basic necessities such as food and monthly bills. (47) Some research suggests that increasing debt loads combined with prolonged high unemployment can lead to a negatively reinforcing cycle of even greater joblessness, debt, and reduced consumption. (48) (49)

Figure 15

Public Policy Responses to the Economic Disruption from COVID-19

Policymakers have been forced to make swift decisions that affect people’s physical, economic, and mental well-being — all with limited information and tremendous uncertainty. (50) The substance, timing, and impact of those decisions have varied widely across the U.S. (51)

State and Federal Responses to Date

Congress has approved significant relief funding for people, businesses, state and local governments, and other organizations. (52) The largest of these to date is the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. (53) It authorized one-time payments to adults below a certain income threshold, greater unemployment benefits, free testing and treatment for COVID-19, forgivable loans to keep businesses afloat and workers on the payroll, emergency funding for the health care system, and direct aid for state and local governments. (54) (55) (56) There is evidence that these efforts have eased the economic burden of the pandemic. (51) More federal relief may follow, but talks have so far broken down along party lines. (57) (58) (59)

Tennessee modified its unemployment benefits to provide swifter assistance to those out of work, but implementation challenges remain. For example, the state waived its usual one-week waiting period. (60) The initial surge of new unemployment claims, however, overwhelmed the system and left many waiting for weeks without income even into late May. (61) (62) Around that same time, Tennessee began using federal CARES Act money to pay unemployment benefits amid concerns that the surge in claims might strain the state’s regular source of funds. (63) (64) (65)

Tennessee is using federal dollars to support emergency relief for working families and some businesses. For example, the state is paying child care assistance for essential workers and emergency cash assistance for families with few resources whose incomes have been significantly affected by coronavirus. (66) (67) The money for these initiatives comes from Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and the Child Care Development Fund (CCDF). (68) (69) Tennessee is also using CARES Act money to assist small businesses affected by closures and counties, cities, and nonprofits responding to COVID-related needs. (70) (71)

Tennessee has also taken steps to connect the unemployed to industries that need workers. Many employers around the country were forced to make tough decisions about managing their cashflow. A surge in business at others, however, led to temporary hiring and pay increases to meet demand (e.g. grocery stores, prepared food, and delivery services). (29) (72) (73) (74) The newly-formed Tennessee Talent Exchange is a public-private partnership between the state and industry associations to rapidly connect people who need jobs with employers that want to hire. (75)

Issues to Consider Going Forward

As the coronavirus pandemic and recession continue to evolve, circumstances will change and specific challenges may grow more or less urgent. Policymakers have no shortage of issues and ideas to consider as this pandemic has created both health and economic consequences that are often complicated and potentially far-reaching. As state leaders consider how best to allocate limited state and federal resources, here is a sampling of the potential economic-related challenges they may want to consider and prepare for:

- Unemployment Insurance – Financial relief was hindered for many who recently tried to access unemployment insurance (UI) benefits but were met with technical glitches and long delays. Going into the recession, the state’s UI resources were also just shy of a federal target for ability to weather a typical recession, and a historic spike in claims raised the prospect of an automatic tax increase on businesses before state officials turned to federal aid.

- Digital Barriers to Assistance — Many applications for economic relief require online forms and weekly check-ins via web-based portals. Not all low-income communities have reliable access to internet to tap into available economic relief.(76)

- Small Business Viability — Small businesses generate more than their share of new jobs, but they can also be particularly vulnerable to recessions.(77) (78) Small businesses, especially those in vulnerable industries, are already having trouble weathering this storm. (79) (80)

- Growth of Personal Debt — Personal debt can cause a cascade of spiraling consequences. The current recession could increase Tennessee’s worse-than-average rates of debt and decrease financial security for those already in debt. (81)(82)

- Labor Force Effects — Some unemployed or furloughed Tennesseans may not yet want to return to work, while many who do face an unusually challenging job market. For any working-age Tennesseans who ultimately drop out of the labor force, long-term unemployment can come with a wide variety of negative effects. (83) (84) (85)

- Schools & Working Parents — While they can help slow the spread of the virus, school closures also reduce the productivity of many working parents, prevent others from returning to work at all, and will likely have implications for longstanding socioeconomic gaps in academic achievement and social development. (86) (87) (88) (89)

- Loss of Job-Based Health Insurance — In addition to losing their jobs, several hundred thousand Tennesseans may also lose their employer-sponsored health insurance. (90) (91) Many will not be eligible for or be able to afford other types of coverage. (92) This could create challenges for accessing any needed health care without incurring medical debt. (93)

- Mental Health Effects of Job Loss & Isolation — People may be suffering from behavioral health complications triggered by COVID-19 and its economic consequences – like anxiety, depression, and addiction. (94)

Parting Words

The economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have rapidly swept through Tennessee and the entire country. Businesses closed their doors for weeks or even months, some for good. Meanwhile, our unemployment rate jumped from 3.3% to 11.3% in the space of 2 months, and about 650,000 people filed new claims for unemployment benefits. As we confront a renewed surge of cases, policymakers may want to focus economic relief on the businesses and workers most at-risk while also tackling the downstream effects of long-term unemployment and social isolation.

*For twelve counties, the number of people working in these industries was too small to be reported due to privacy concerns. The data for these counties are included, however, at higher levels of aggregation (e.g. state totals). (24)

References

Click to Open/Close

- Malone, Claire and Bourassa, Kyle. Americans Didn’t Wait for Their Governors to Tell Them to Stay Home Because of COVID-19. FiveThirtyEight. [Online] May 8, 2020. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/americans-didnt-wait-for-their-governors-to-tell-them-to-stay-home-because-of-covid-19/.

- Badger, Emily and Parlapiano, Alicia. Government Orders Alone Didn’t Close the Economy. They Probably Can’t Reopen It. The New York Times. [Online] May 7, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/07/upshot/pandemic-economy-government-orders.html.

- Rogoff, Kenneth. Mapping the COVID-19 Recession. Project Syndicate. [Online] April 7, 2020. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/mapping-covid19-global-recession-worst-in-150-years-by-kenneth-rogoff-2020-04.

- Stewart, Emily. The Coronavirus Recession is Already Here. Vox. [Online] March 26, 2020. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2020/3/21/21188541/coronavirus-news-recession-economy-unemployment-stock-market-jobs-gdp.

- Carlsson-Szlezak, Philipp, Reeves, Martin and Swartz, Paul. Understanding the Economic Shock of Coronavirus. Harvard Business Review. [Online] March 27, 2020. https://hbr.org/2020/03/understanding-the-economic-shock-of-coronavirus.

- Lachman, Desmond. How the Coronavirus Could Crush the U.S. Economy. The National Interest. [Online] June 22, 2020. https://nationalinterest.org/blog/coronavirus/how-coronavirus-could-crush-us-economy-163224.

- Smith, Noah. The U.S. is Battling Two Recessions, Not Just One. Bloomberg. [Online] July 9, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-07-09/u-s-economy-is-battling-two-coronavirus-recessions-not-just-one.

- Jeong, Yihyun and Kelman, Brett. Nashville Shutters Bars, Calls Off Fireworks Ahead of July 4 as Coronavirus Spikes. The Tennessean. [Online] July 2, 2020. https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/politics/2020/07/02/nashville-adds-restaurant-restrictions-as-coronavirus-spreads/5351136002/.

- The Job Quality Index. Statement #3 from the U.S. Private Sector Job Quality Index (“JQI”) Team on Economic Impacts of COVID-19 Related Unemployment. Cornell Law School. [Online] June 1, 2020. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/prosperousamerica/pages/5561/attachments/original/1590954099/JQI_Team_Statement_on_COVID-19_Economic_Shutdown_Job_Impact_052920.pdf?1590954099.

- Dey, Matthew and Loewenstein, Mark A. How Many Workers Are Employed in Sectors Directly Affected by COVID-19 Shutdowns, Where Do They Work, and How Much Do They Earn? U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics: Monthly Labor Review. [Online] April 2020. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2020/article/covid-19-shutdowns.htm.

- Kochhar, Rakesh and Passel, Jeffrey. Telework May Save U.S. Jobs in COVID-19 Downturn, Especially Among College Graduates. Pew Research Center. [Online] May 6, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/05/06/telework-may-save-u-s-jobs-in-covid-19-downturn-especially-among-college-graduates/.

- Chetty, Raj, et al. Real-Time Economics: A New Platform to Track the Impacts of COVID-19 on People, Businesses, and Communities Using Private Sector Data. Opportunity Insights. [Online] July 2020. https://tracker.opportunityinsights.org/.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Local Area Unemployment Statistics. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Online] June 30, 2020. https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LASST470000000000003.

- Murray, Matthew, Cahill, Katie and Daugherty, Linda. The Tennessee Pulse Survey (Wave 2). University of Tennessee Knoxville. [Online] June 7, 2020. [Cited: July 6, 2020.] http://core19.utk.edu/tn-pulse-wave-2.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Tennessee Economy at a Glance. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Online] June 30, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/regions/southeast/tennessee.htm.

- U.S. Department of Labor: Employment & Training Administration. State Weekly Claims for Unemployment Insurance Data Not Seasonally Adjusted. U.S. Department of Labor. [Online] June 30, 2020. https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/claims.asp.

- U.S. Department of Labor. Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims: Week Ending June 20. U.S. Department of Labor. [Online] June 25, 2020. https://www.dol.gov/ui/data.pdf.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Quarterly Census of Employment & Wages. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Online] December 4, 2019. https://data.bls.gov/cew/doc/access/csv_data_slices.htm#AREA_SLICES.

- U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Special Report on Coronavirus and Small Business. U.S. Chamber of Commerce. [Online] April 3, 2020. https://www.uschamber.com/report/special-report-coronavirus-and-small-business.

- Şahin, Ayşegül, et al. Why Small Businesses Were Hit Harder by the Recent Recession. Federal Reserve Bank of New York. [Online] July 21, 2011. https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/current_issues/ci17-4.pdf.

- NFIB Research Center. Covid-19 Small Business Survey(8). NFIB. [Online] June 23, 2020. https://assets.nfib.com/nfibcom/Covid-19-8-Write-up-and-Questionnaire-6-16-2020-FINAL.pdf.

- Tennessee Government. Labor Force, Employment and Unemployment for Tennessee in May, 2020. Jobs4TN. [Online] Jun 30, 2020. https://www.jobs4tn.gov/vosnet/analyzer/results.aspx?enc=HofuwY22SoLTS/uC+bpmizGZkm52zV+sR+lKAe/bUj0=.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Force Data by County, Not Seasonally Adjusted, Latest 14 Months. [Online] June 30, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/web/metro/laucntycur14.txt.

- —. QCEW Questions and Answers. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Online] September 26, 2019. https://www.bls.gov/cew/questions-and-answers.htm.

- Hoynes, Hilary, Miller, Douglas L. and Schaller, Jessamyn. Who Suffers During Recessions? Journal of Economic Perspectives. [Online] 26(3) 2012. https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.26.3.27.

- Verick, Sher. Who Is Hit Hardest During a Financial Crisis?The Vulnerability of Young Men and Women to Unemployment in an Economic Downturn. IZA Institute fo Labor Economics. [Online] August 2009. http://ftp.iza.org/dp4359.pdf.

- Berube, Alan and Bateman, Nicole. Who are the Workers Already Impacted by the COVID-19 Recession. The Brookings Institution. [Online] April 3, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/research/who-are-the-workers-already-impacted-by-the-covid-19-recession/.

- MacDonald, Graham, et al. Where Low-Income Jobs Are Being Lost to COVID-19. The Urban Institute. [Online] April 24, 2020. https://www.urban.org/features/where-low-income-jobs-are-being-lost-covid-19.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Employment Situation – April 2020. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Online] May 8, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2018 ACS 1-Year Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. [Online] 11 14, 2019. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data/data-via-ftp.html.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employment Status of the Civilian Noninstitutional Population in States by Sex, Race, Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity, Marital Status, and Detailed Age (1999-2020 Annual Averages). [Online] [Cited: July 6, 2020.] Available from https://www.bls.gov/lau/ex14tables.htm.

- Cox, Daniel A. Hardship, Anxiety, and Optimism: Racial and Partisan Disparities in Americans’ Response to COVID-19. American Enterprise Institute. [Online] June 16, 2020. https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/hardship-anxiety-and-optimism-racial-and-partisan-disparities-in-americans-response-to-covid-19/.

- Congressional Budget Office. Interim Economic Projections for 2020 and 2021. Congress of the United States. [Online] May 19, 2020. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2020-05/56351-CBO-interim-projections.pdf.

- Smialek, Jeanna. Fed Leaves Rates Unchanged and Projects Years of High Unemployment. The New York Times. [Online] June 10, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/10/business/economy/federal-reserve-economy-coronavirus.html.

- Nichols, Austin, Mitchell, Josh and Lindner, Stephan. Consequences of Long-Term Unemployment. The Urban Institute. [Online] July 2013. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/23921/412887-Consequences-of-Long-Term-Unemployment.PDF.

- Borie-Holtz, Debbie, Van Horn, Carl and Zukin, Cliff. No End in Sight: The Agony of Prolonged Unemployment. John J. Heldrich Center for Workplace Development. [Online] May 2010. https://www.heldrich.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/products/uploads/Work_Trends_May_2010_0.pdf.

- Brunner, Beatrice and Kuhn, Andreas. The Impact of Labor Market Entry Conditions on Initial Job Assignment and Wages. Journal of Population Economics. [Online] 27(3) 2014. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00148-013-0494-4.

- Oreopoulos, Philip, von Wachter, Till and Hiesz, Andrew. The Short- and Long-Term Career Effects of Graduating in a Recession. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. [Online] 4(1) 2012. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/app.4.1.1.

- Popper, Nathaniel. Young Adults, Burdened With Debt, Are Now Facing an Economic Crisis. The New York Times. [Online] April 6, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/business/millennials-economic-crisis-virus.html.

- Federal Reserve Board of Governors. Survey of Consumer Finance. Federal Reserve Board of Governors. [Online] 10 31, 2017. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scfindex.htm#table1.

- Boshara, Ray, Emmons, William R. and Noeth, Bryan J. The Demographics of Wealth: How Age, Education and Race Separate Thrivers from Strugglers in Today’s Economy (Essays 1-3). Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. [Online] Feb, May, June 2015. https://www.stlouisfed.org/household-financial-stability/the-demographics-of-wealth.

- Schwartz, Nelson D., Casselman, Ben and Koeze, Ella. How Bad is Unemployment? ‘Literally of the Charts’. The New York Times. [Online] May 8, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/05/08/business/economy/april-jobs-report.html.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Current Employment Statistics Highlights. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Online] June 5, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/ces/publications/highlights/2020/current-employment-statistics-highlights-05-2020.pdf.

- Hawkins, Melissa. The US Isn’t In a Second Wave of Coronavirus – The First Wave Never Ended. The Conversation. [Online] June 30, 2020. https://theconversation.com/the-us-isnt-in-a-second-wave-of-coronavirus-the-first-wave-never-ended-141032.

- Braga, Breno, McKernan, Signe-Mary and Quakenbush, Caleb. Debt in America: An Interactive Map. The Urban Institute. [Online] December 17, 2019. https://apps.urban.org/features/debt-interactive-map/downloadable-docs/Debt_in_America_Technical_Appendix.pdf.

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit: Statistics by State 1999-2019. Center for Microeconomic Data. [Online] Febuary 2020. Accessed from https://www.newyorkfed.org/microeconomics/databank.

- Boshara, Ray. Is Record High Consumer Debt a Boon or Bane? Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis On the Economy Blog. [Online] December 19, 2017. https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2017/december/consumer-debt-boon-bane.

- Eggertsson, Gauti B. and Krugman, Paul. Debt, Deleveraging, and the Liquidity Trap: A Fisher-Minsky-Koo Approach. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. [Online] 127(3) 2012. https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/127/3/1469/1924252?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

- Mian, Atif R. and Sufi, Amir. What Explains High Unemployment? The Aggregate Demand Channel. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Online] February 2012. https://www.nber.org/papers/w17830.

- Roberts, Siobhan. Embracing Uncertainty. The New York Times. [Online] April 7, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/07/science/coronavirus-uncertainty-scientific-trust.html.

- Meyer, Bruce D. Income and Poverty in the COVID-19 Pandemic. The Brookings Institution. [Online] June 25, 2020. https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/income-and-poverty-in-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

- Ferguson, Peter G. Here’s Everything Congress Has Done to Respond to the Coronavirus So Far. Peter G. Ferguson Foundation. [Online] April 24, 2020. https://www.pgpf.org/blog/2020/04/heres-everything-congress-has-done-to-respond-to-the-coronavirus-so-far.

- U.S. Congress. Cares Act, H.R. 748, 116th Cong. [Online] 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748.

- Snell, Kelsey. What’s Inside the Senate’s $2 Trillion Coronavirus Aid Package. National Public Radio. [Online] March 26, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/03/26/821457551/whats-inside-the-senate-s-2-trillion-coronavirus-aid-package.

- Watson, Garrett, et al. Congress Approves Economic Relief for Individuals and Businesses. Tax Foundation. [Online] March 30, 2020. https://taxfoundation.org/cares-act-senate-coronavirus-bill-economic-relief-plan/.

- —. Congress Approves Economic Relief Plan for Individuals and Businesses. Tax Foundation. [Online] March 30, 2020. https://taxfoundation.org/cares-act-senate-coronavirus-bill-economic-relief-plan/.

- Nilsen, Ella. What We Know About the Next Coronavirus Funding Package. Vox. [Online] April 29, 2020. https://www.vox.com/2020/4/29/21227979/what-we-know-next-coronavirus-funding-package-states.

- Stein, Jeff, Dawsey, Josh and Werner, Erica. Trump Tells Aides He Supports Second Round of Stimulus Checks, but White House Divisions Remain. The Washington Post. [Online] June 23, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/06/23/trump-stimulus-checks-second-round/.

- Hayes, Christal and Collins, Michael. More Checks? A Payroll Tax Cut? Trump and Congress Split on Next Coronavirus Relief Plan. USA Today. [Online] May 11, 2020. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2020/05/11/coronavirus-trump-congress-split-stimulus-address-covid-19/5176373002/.

- Lee, Bill. An Order Suspending Provisions of Certain Statutes and Rules and Taking Other Necessary Measures in Order to Facilitate the Treatment and Containment of COVID-19. [Online] March 19, 2020. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/pub/execorders/exec-orders-lee15.pdf.

- Stephenson, Cassandra. No Payments, No Answers and Weeks of Wait: For Some Tennesseans, Filing for Unemployment Has Been ‘A Disaster’. The Tennessean. [Online] April 29, 2020. https://www.tennessean.com/story/money/2020/04/30/tennessee-unemployment-filing-has-been-a-disaster/3003639001/.

- —. TN UNemployment Has Surged and Thousands Haven’t Received Benefits. What is the State Doing to Help? The Tennessean. [Online] May 22, 2020. https://www.tennessean.com/story/money/2020/05/22/what-tennessee-doing-help-those-waiting-unemployment-benefits/5236539002/.

- Ebert, Joel. Even Before COVID-19 Economic Crisis, Tennessee’s Unemployment Fund Below Recommended Level. The Tennessean. [Online] May 3, 2020. https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/politics/2020/05/03/even-before-covid-19-tennessees-unemployment-fund-below-recommended-level/3059335001/.

- Sher, Andy. Masive Unemployment Claims Put Tennessee Trust Fund Under Pressure. Chattanooga Times Free Press. [Online] May 10, 2020. https://www.timesfreepress.com/news/local/story/2020/may/10/massive-unemployment-claims-put-tennessee-tru/522666/.

- Walczak, Jared. States’ Unemployment Compensation Trust Funds Could Run Out in Mere Weeks. Tax Foundation. [Online] April 9, 2020. https://taxfoundation.org/state-unemployment-compensation-trust-funds-run-mere-weeks/.

- Tennessee Department of Human Services. Child Care. [Online] [Cited: May 29, 2020.] https://www.tn.gov/humanservices/covid-19/child-care-services-and-covid-19.html.

- —. Emergency Cash Assistance. [Online] [Cited: May 29, 2020.] https://www.tn.gov/humanservices/covid-19/emergency-cash-assistance-and-covid-19-faqs.html.

- —. Program to Provide Free Child Care for Essential Workers Expanded. Tennessee Department of Human Services. [Online] May 21, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/humanservices/news/2020/5/21/program-to-provide-free-child-care-for-essential-workers-expanded.html.

- —. Tennessee Making it Possible for More Families to Receive COVID-19 Assistance. Tennessee Department of Human Services. [Online] June 30, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/humanservices/news/2020/6/30/tennessee-making-it-possible-for-more-families-to-receive-covid-19-assistance.html.

- State of Tennessee. Tennessee Business Relief Program. [Online] June 2020. [Cited: July 6, 2020.] https://www.tn.gov/revenue/tennessee-business-relief-program.html.

- Tennessee Office of the Governor. Tennessee to Distribute $200 Million to County and City Governments Through Governor’s Local Support Grants . Tennessee Office of the Governor. [Online] April 6, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/governor/news/2020/4/6/tennessee-to-distribute–200-million-to-county-and-city-governments-through-governor-s-local-support-grants-.html.

- Garcia, Jon. Who is Hiring in Nashville and Middle Tennessee During Coronavirus Pandemic. The Tennessean. [Online] March 23, 2020. https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/local/2020/03/23/jobs-hiring-nashville-tennessee-during-coronavirus/2898394001/.

- McDermott, Brenna. Looking For a Job? These Businesses Are Hiring. Knox News. [Online] March 25, 2020. https://www.knoxnews.com/story/money/2020/03/25/knoxville-east-tennessee-jobs-whos-hiring-during-coronavirus-crisis/5077895002/.

- Molla, Rani. Not Everyone is Laying Off Workers Because of Coronavirus. These Are the Most In-Demand Jobs Right Now. Vox. [Online] March 26, 2020. https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/3/26/21195150/jobs-demand-coronavirus-linkedin-7-eleven.

- Tennessee Office of the Governor. COVID-19 Bulletin 7. Tennessee Office of the Governor. [Online] March 26, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/governor/covid-19/covid-19-daily-bulletin/2020/3/26/covid-19-bulletin-7—march-26–2020.html.

- National Consumer Law Center. Digital Divide: Millions of American Have Limited or No Meaningful Access to the Internet. National Consumer Law Center. [Online] August 2019. https://www.nclc.org/issues/ib-limited-access-to-internet.html.

- U.S. Small Business Administration. 2018 Small Business Profile: Tennessee. [Online] 2018. https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/advocacy/2018-Small-Business-Profiles-TN.pdf.

- —. What’s New With Small Business? [Online] August 2018. https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/Whats-New-With-Small-Business-2018.pdf.

- Parilla, Joseph, Liu, Sifan and Whitehead, Brad. How Local Leaders Can Stave Off a Small Business Collapse From COVID-19. The Brookings Institution. [Online] April 3, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/research/how-local-leaders-can-stave-off-a-small-business-collapse-from-covid-19/.

- White, Adam J. Deregulate for the Coronavirus Recovery. The Wall Street Journal. [Online] May 3, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/deregulate-for-the-coronavirus-recovery-11588542052.

- Warren, Andrew, McKernan, Signe-Mary and Braga, Breno. Before COVID-19, 68 Million US Adults Had Debt in Collections. What Policies Could Help? The Urban Insititute. [Online] April 17, 2020. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/covid-19-68-million-us-adults-had-debt-collections-what-policies-could-help.

- National Consumer Law Center. What States Should Do: Stabilizing Consumer Finances During the Coronavirus Crisis. National Consumer Law Center. [Online] April 2020. https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/special_projects/covid-19/WSCD_Summary_Crisis.pdf.

- Haddon, Heather and Chen, Te-Ping. Restaurants Reopen, but Not Everyone Is Coming Back to Work. The Wall Street Journal. [Online] May 7, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/restaurants-reopen-but-not-everyone-is-coming-back-to-work-11588843808.

- Romm, Tony. ‘It’s Too Early to Go Back’:Workers Fear for Their Health and Finances as States Rush to Reopen. The Washington Post. [Online] May 8, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/05/08/workers-unemployment-states-reopen/.

- Blake, Suzanne. The Class of 2020 is Getting a Crash Course in Pivoting – Changing Their Career Outlook, Delaying Graduation – Whatever it Takes. CNBC. [Online] July 10, 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/10/its-a-tough-job-outlook-for-college-graduates-in-the-class-of-2020.html.

- Tarasawa, Beth. COVID-19 School Closures Could Have a Devastating Impact on Student Achievement. NWEA. [Online] April 9, 2020. https://www.nwea.org/blog/2020/covid-19-school-closures-could-have-devastating-impact-student-achievement/.

- Kelly, Mary Louise. The Long-Term Effects of Months-Long School Closures on U.S. Children. NPR. [Online] April 24, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/04/24/844562989/the-long-term-effects-of-months-long-school-closures-on-u-s-children.

- Tankersley, Jim and Casselman, Ben. A Resurgence of the Virus, and Lockdowns, Threatens Economic Recovery. The New York Times. [Online] July 15, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/15/business/economy/economic-recovery-coronavirus-resurgence.html.

- Couzin-Frankel, Jennifer, Vogel, Gretchen and Weiland, Meagan. School Openings Across Globe Suggest Ways to Keep Coronavirus at Bay, Despite Outbreaks. Science. [Online] July 7, 2020. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/07/school-openings-across-globe-suggest-ways-keep-coronavirus-bay-despite-outbreaks.

- Biven, Josh and Zipperer, Ben. 12.7 Million Workers Have Likely Lost Employer-Provided Health Insurance Since the Coronavirus Shock Began. The Economic Policy Institute. [Online] April 30, 2020. https://www.epi.org/blog/12-7-million-workers-have-likely-lost-employer-provided-health-insurance-since-the-coronavirus-shock-began/.

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. How the COVID-19 Recession Could Affect Health Insurance Coverage. [Online] May 4, 2020. [Cited: June 11, 2020.] Study accessed from https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2020/05/how-the-covid-19-recession-could-affect-health-insurance-coverage.html?cid=xem_other_unpd_ini:quick%20strike_dte:20200504_des:quick%20strike.

- Rachel Garfield, Gary Claxton, Anthony Damico, Larry Levitt. Eligibility for ACA Health Coverage Following Job Loss. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Online] May 13, 2020. [Cited: June 11, 2020.] https://www.kff.org/report-section/eligibility-for-aca-health-coverage-following-job-loss-appendix/.

- Tolbert, Jennifer, et al. State Data and Policy Actions to Address Coronavirus. The Kaiser Family Foundation. [Online] May 5, 2020. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/state-data-and-policy-actions-to-address-coronavirus/.

- Wan, William. The Coronavirus Pandemic is Pushing America Into a Mental Health Crisis. The Washington Post. [Online] May 4, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/05/04/mental-health-coronavirus/.

Featured photo by nimito/Shutterstock.com