The coronavirus pandemic has caused a historic spike in people filing for unemployment benefits. This report looks at Tennessee’s unemployment insurance (UI) program — what it is, who it covers, how it’s funded, where it stands compared to other states, and what’s been changed recently.

Key Takeaways

- Unemployment insurance is intended to stabilize family finances and economic activity when people lose jobs.

- Each state designs its own UI program within broad federal parameters. Tennessee’s unemployment benefits and related employer taxes are among the lowest in the nation.

- Over the last two decades, Tennesseans have been less likely than other out-of-work Americans to get unemployment benefits. Meanwhile, the value of those benefits has fallen.

- Tennessee began using federal coronavirus relief funds in late May to pay benefits after the recent historic influx of claims was projected to strain the state’s unemployment trust fund.

What Is Unemployment Insurance?

The state-federal unemployment insurance (UI) program is a safety net for both workers and the economy. Created in 1935 in the midst of the Great Depression, the program temporarily replaces a portion of worker wages when they lose their jobs. Like other types of insurance, it is meant to protect against uncertainty. UI reduces the risk of financial instability for workers and their families, while also keeping consumer dollars flowing through the economy. (3) (4) (5)

Unemployment benefits can help to stabilize family finances and economic activity but may also discourage quick re-employment in certain situations. Some research suggests that longer and/or more generous benefits may increase the duration of unemployment when jobs are readily available, but overall, the evidence is mixed. (6) (7) (8) (9) The additional benefits currently available from the federal government (discussed below) were, in part, meant to encourage workers to stay home and slow the spread of COVID-19. (10)

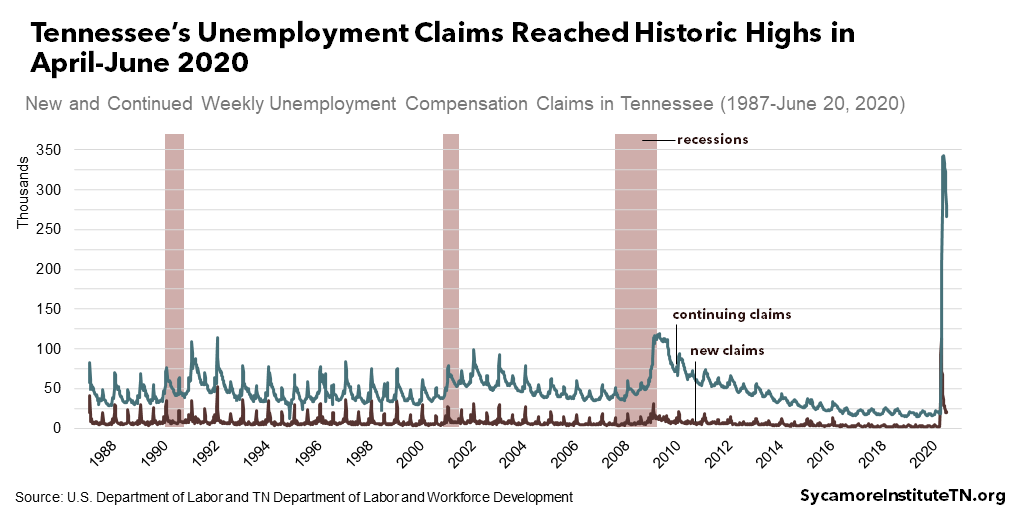

Unemployment insurance is a countercyclical program, meaning more people apply for benefits during economic downturns. To prepare for this demand, states set aside money for unemployment compensation during periods of high employment and economic growth. While benefit claims typically rise during recessions, the surge in UI claims in April, May, and June 2020 far exceeds any other in recent memory (Figure 1). (1) (11)

Figure 1

Each state designs its own UI program within broad federal parameters. States set and administer their own rules for benefits, eligibility, and funding. The federal government oversees these programs, pays for administrative costs, and manages and invests each state’s unemployment trust fund. (3) (4)

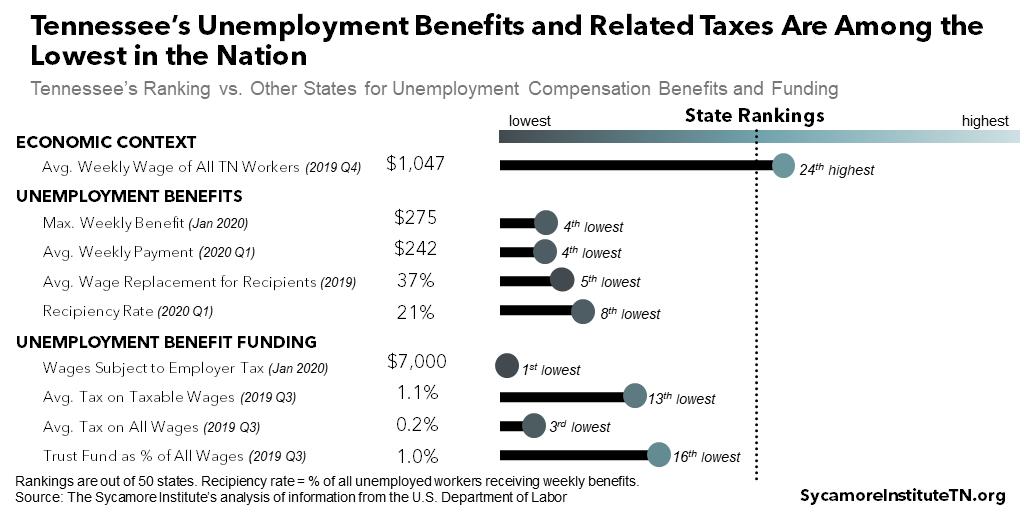

Tennessee’s unemployment benefits and related employer taxes are among the lowest in the nation (Figure 2). Tennessee businesses have a lower unemployment tax burden than those in all but two other states. The trade-offs are less generous benefits for out-of-work Tennesseans (even after adjusting for local wages) and an unemployment trust fund with less capacity than in most other states.

Figure 2

Who Gets Unemployment Benefits in Tennessee

Eligibility for unemployment insurance varies significantly by state and is often tweaked during economic downturns. Unless we note otherwise, the information here applies to Tennessee’s “standard” criteria as of January 2020 before the coronavirus pandemic.

Determining Eligibility

Standard unemployment benefits are reserved for people who — through no fault of their own —lose a job from one of the covered businesses outlined below. Those who voluntarily leave a job without “good cause” are not eligible. In Tennessee, “good cause” must be work-related or due to mandatory retirement or sexual or other harassment. (16) (17) In March 2020, Gov. Lee signed an executive order making workers ordered to isolate or quarantine due to coronavirus eligible. (18)

The federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act extended benefits to independent contractors and the self-employed, who usually can’t access UI in Tennessee. As of 2019, 10 states allowed some self-employed workers to get UI benefits. Tennessee did not have a similar program in place for the self-employed before Congress passed the CARES Act in March, and no state covered independent contractors. The CARES Act eligibility expires on December 31, 2020. (16)

Each person’s eligibility depends on their wages before filing an unemployment claim. In Tennessee, a worker must have earned at least $780 in each of two quarters within the base period — defined as the first 12 out of 15 months preceding an initial claim. (19) (20) (21)

Recipiency Rate

Tennessee’s UI program provided benefits to about 21% of the state’s unemployed workers in the first quarter of 2020. That puts Tennessee’s recipiency rate at the 8th lowest in the country (Figure 2). (12) Historically, the state’s recipiency rate closely mirrored the nation’s. Since 2004, however, Tennessee’s rate has ranged about 10-15 percentage points below the U.S. rate (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Unemployed workers may not receive UI benefits if they do not or no longer qualify. A person may not qualify if their wages were too low, they are a contractor, they fail to meet program requirements, or they exhaust their benefits after being unemployed for a long period of time.

A number of program requirements can disqualify people from receiving benefits. For example, the state can reduce or suspend someone’s benefits if they decline or fail an employer-administered drug test, don’t adequately document searching for a new job, or turn down a suitable job offer (defined primarily by pay and how it relates to prior wages). (21) (16) (22) (17) Many of these requirements and the associated penalties and enforcement mechanisms have been added or expanded since the last recession. (23) (24) (25) (26) (27) An executive order that expires on August 29, 2020 waives Tennessee’s requirements to seek work and have in-person check-ins. (18) (28) (29)

For various reasons, out-of-work individuals might not even apply for unemployment compensation. For example, they may not know the benefits are available, how to apply, or that they are eligible. They may not have access to the technology needed to apply, expect to find a new job quickly, or view the amount of money or paperwork as not worthwhile — especially in a strong job market. (30) (31) Recent data suggest that fewer of Tennessee’s workers have filed for unemployment during the pandemic compared to other states. (32)

Challenges of the Coronavirus Pandemic

Tennessee and other states faced operational challenges in the wake of the pandemic that have also affected eligible workers’ access to benefits. The unprecedented surge in applications overwhelmed many states’ systems, creating a backlog of eligible workers waiting for approval. Tennessee has made efforts to facilitate the process by hiring more staff and staggering certification schedules. (33) (34) (35)

As state and local officials lift restrictions, some Tennesseans receiving unemployment may be reluctant to return to work. Fears of catching and spreading the virus, confusing public health recommendations, generous federally-funded benefits, and lack of child care may all factor into that calculation. Meanwhile, some businesses worry they may be unable to operate normally if employees won’t return to work. People with higher risks (e.g. underlying health conditions, living with older adults, etc.) or returning to jobs in “customer-facing” industries may be particularly resistant to go back to work. For some, an additional $600 federal UI benefit also makes staying home both financially possible and rational. However, rejecting valid offers of employment generally makes someone ineligible for continued UI benefits. Tennessee and the federal government continue to enforce that rule, but some states have loosened this restriction to varying degrees. (36) (37) (38) (39) (40) (41) (42) (43)

Unemployment Compensation Offered by Tennessee

Payment Amounts

In Tennessee, weekly UI benefits range from $30 to $275 based on prior wages. Each individual receives about 3.8% of their average wages in the two highest-earning quarters of the base period — up to the $275 maximum. (44) To receive the max $275 per week payment, an individual would have to make more than $14,300 over the course of two quarters. (16) (14) (20)

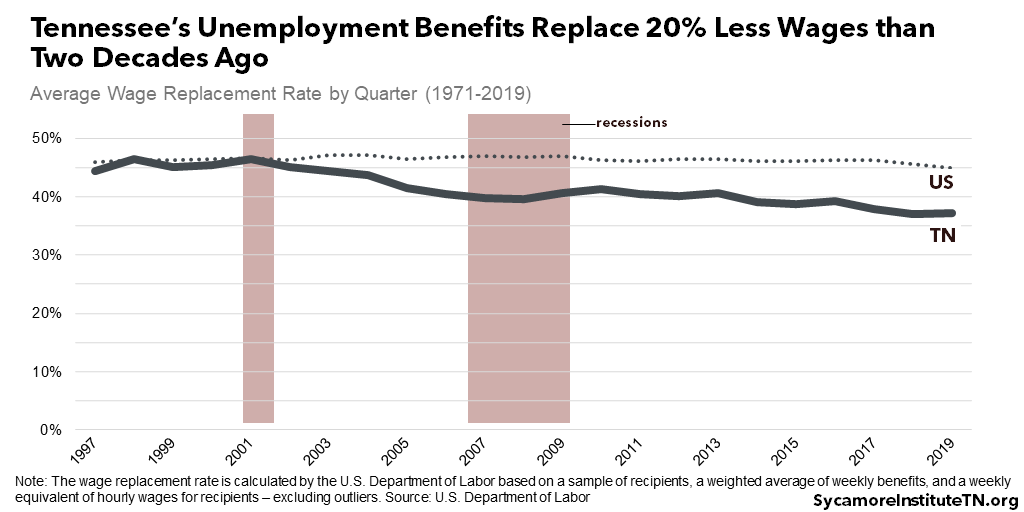

The state’s benefit amounts have not changed since 2001 and don’t go as far as they use to. In 2019, Tennessee’s average weekly benefits replaced about 20% less wages than they did in 2001, when the maximum benefit was raised from $255 per week to $275 (Figure 4). (12) (45) Prior to 2001, state lawmakers updated Tennessee’s weekly benefit levels about every two years. (44)

Figure 4

Tennessee’s average UI payment in the first quarter of 2020 was $242 per week, the 4th lowest in the U.S. Nationally, average weekly benefits range from $213 in Mississippi to $552 in Massachusetts (Figure 2). (12) For context, Tennessee’s average weekly wage for all Tennessee workers was lower than 23 other states at the end of 2019. (15)

Adjusting for differences in recipients wages, Tennessee’s UI payments replaced roughly 37% of the average wages of those receiving benefits in 2019. This was the 5th lowest wage replacement rate in the country, which varied from 31% in Alaska to 54% in Hawaii (Figure 2). (13)

The CARES Act funds an additional $600 per week for UI recipients through July 31, 2020 (Figure 5). (46) This more than triples the amount of unemployment benefits available to eligible Tennesseans during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some argue the significant increase in benefits discourages people from returning to work as businesses open back up, while others contend they are needed to encourage workers to stay home and slow the spread of the virus. (10)

Unemployment benefits are subject to certain deductions but cannot be seized to pay off pre-existing debts. Income taxes, child support payments, and food stamp overpayments can all be deducted from UI benefits. (20) (47) (48) However, benefits cannot be garnished or seized to collect a debt, unless the person incurred that debt while unemployed and receiving benefits. (49)

Waiting Periods

Tennesseans who qualify must wait one week between approval for UI and their first payment. (22) After receiving three weeks of payments, individuals can receive payment for the initial waiting week. Among the 42 states with a waiting week, Tennessee is one of only four that compensates people for the waiting period. (16)

The CARES Act provides federal funding for a week of benefits for states that waive their one-week waiting period. (46) Tennessee waived its one-week waiting period beginning in March through executive orders that expire on August 29, 2020. (18) (28) (29)

Time Limits

Tennessee provides standard UI benefits for up to 26 weeks. Tennessee is among 41 states with a 26-week limit. Seven states have shorter limits, and two have longer ones. (16)

All states provide up to an additional 13 weeks of extended benefits (EB) when the unemployment rate among eligible workers is high. Tennessee provides EB when the unemployment rate among eligible workers is at least 6% for 13 weeks or more. Under federal rules, states must also provide EB when the unemployment rate among eligible workers is both 1) at least 5% for 13 or more weeks and 2) unusually high compared to previous years. (16) (50)

The federal government splits the cost of extended benefits with states and often chips in more during economic downturns. During ordinary times, the federal government pays for half of EB costs. During downturns, Congress often extends the EB period and/or cover the entire costs of EB. (16) (4)

Under the CARES Act, the federal government will fully pay for three types of extended and additional UI benefits (Figure 5).

- 13 weeks of Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) through December 31, 2020 for those who max out their standard state benefits.

- Another 13 weeks of EB for individuals who exhaust PEUC in states that meet the EB unemployment triggers above.

- Up to 39 weeks of Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) through December 31, 2020 for individuals who exhaust both PEUA and EB and for those not usually eligible for UI in their state (e.g. independent contractors).(46)

Figure 5

Other Arrangements and Additional Benefits Outside Tennessee

Other states provide for alternative arrangements and/or additional benefits beyond those outlined above that are not currently available in Tennessee.

Twenty-eight states have work-sharing programs that provide UI benefits for employees’ whose hours have been cut by at least 10%. Established by Congress in 2012, optional work-share programs are meant to encourage employers to avoid layoffs for some by scaling back hours for all employees while maintaining their other fringe benefits (e.g. health insurance, retirement). (16) The CARES Act provides federal support for new and existing work-share programs through December 31, 2020. (46)

Thirteen states adjust benefits for dependent children or non-working dependents. An additional weekly allowance for dependents ranges from $8/week max in Pennsylvania to as much as $397/week in Massachusetts. (16)

Twenty-two other states also provide additional benefits in other circumstances. For example, some states provide up to 13 weeks of UI to unemployed workers who are otherwise ineligible. Some states also offer additional weeks of UI for individuals in approved training programs. (16)

How Tennessee Pays for Unemployment Benefits

Unemployment compensation is funded by state and federal payroll taxes on employers. As of 2019, Tennessee employers paid a 6% federal tax and about a 1% state tax on the first $7,000 of each employee’s wages. (12) (51) From those revenue streams, states fund standard UI benefits while the federal government covers state and federal administrative costs and the federal share of extended benefits. The U.S. Treasury’s Unemployment Trust Fund (UTF) manages all of this money with a separate account for each state. (16)

Tennessee’s payroll tax applied to about 130,000 employers and covered 92% of the state’s employed labor force in 2019. (12) Covered employers include private businesses and state and local governments. There are separate standards for certain industries and employment arrangements — including nonprofits, agriculture, domestic service, and seasonal employment. (16) (14) (52) (53) (54)

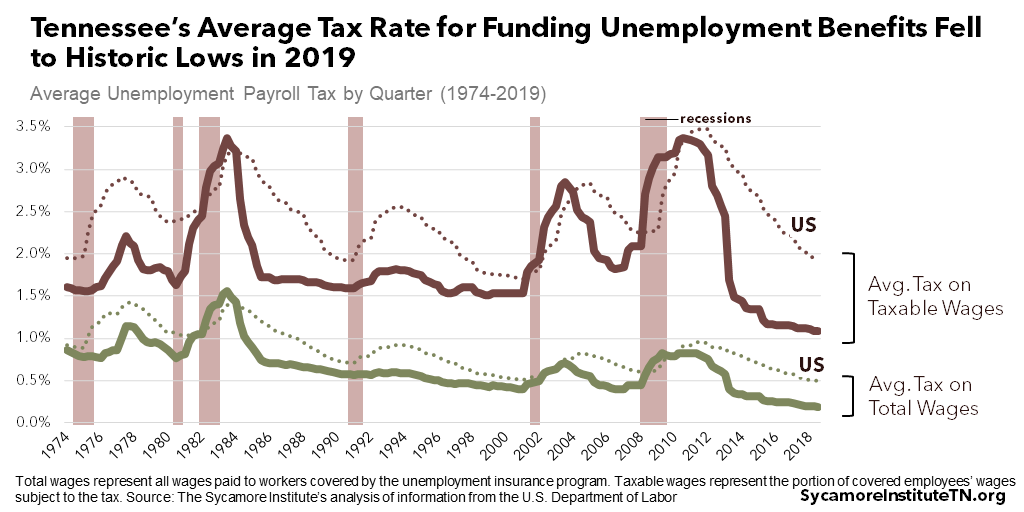

In early 2019, Tennessee’s tax amounted to about 0.2% of all wages, on average — a historically low rate and the 3rd lowest in the country (Figures 2 and 6). At its peak in 1984, the state’s unemployment payroll tax had an average rate of 1.6%. It has steadily declined each quarter since 2012 (Figure 6). (12)

Figure 6

Taxable Wages

The amount of wages subject to the state’s unemployment payroll tax varies based on the size of the trust fund. From 2009-2015, for example, Tennessee’s taxable wage base grew to a high of $9,000 in order to fund UI benefits during and after the last recession. (12) As of January 2020, Tennessee’s $7,000 taxable wage base was tied for the lowest in the country with Arizona, Arkansas, and Florida. The highest was $52,700 in Washington (Figure 2). (14)

Tax Rate

Tennessee’s unemployment payroll tax rate ranges from 0.01% to 10%, depending on circumstances. Each employer’s tax rate is determined by a schedule of 144 possible scenarios that consider employer-specific circumstances and the size of the state’s trust fund. (51) Tennessee has the broadest range of any state, with one of the lowest minimum rates and the highest maximum rate. (16) (14)

The state rate paid by each Tennessee employer depends on their payroll and the amount of benefits paid out to their former employees. This structure is meant to discourage layoffs. Each employer contributes to a separate account, which pays out when their former employees claim benefits. The employer-specific tax rate is based on the ratio of their account balance to their total wages — a practice known as “experience rating.” When benefit payments increase, the tax rate rises to replenish that employer’s account. The minimum rate applies to employers with account balances of at least 20% of their payroll, while the maximum rate applies to those with a deficit of 20% or more of their payroll. (51) (16) (55) (56)

The state’s tax rate also varies based on the size of the trust fund. When Tennessee’s fund balance exceeds $850 million, the minimum tax is 0.01%. When it falls below $450 million, the minimum tax increases to 0.5%. Only three other states base their tax rate on a nominal trust fund balance. At least 29 states and DC instead vary their tax based on the trust fund’s spending power (e.g. as a percent of payroll or compared to prior benefit payouts). (16)

Figure 7

Tennessee’s Unemployment Trust Fund

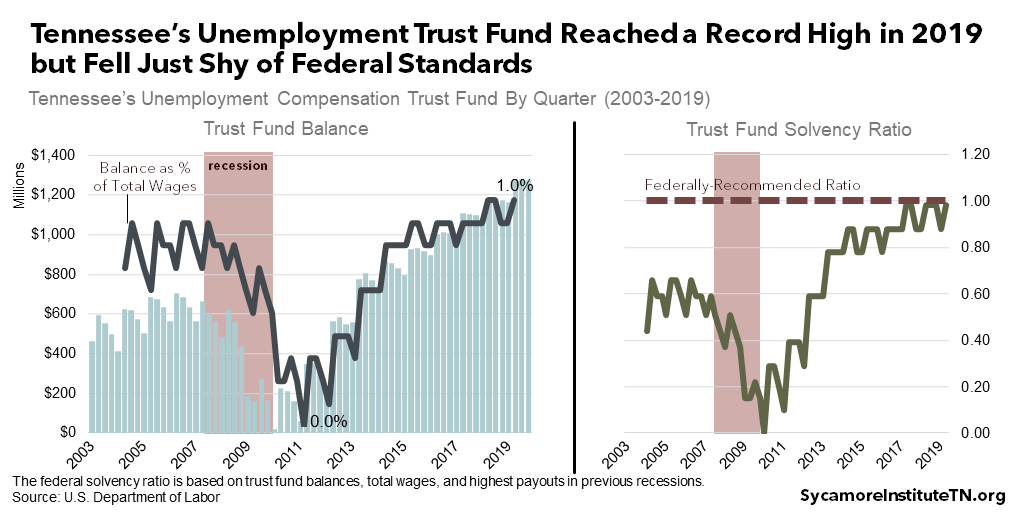

As of March 1, 2020, Tennessee’s unemployment trust fund balance totaled $1.3 billion. (57) This represented Tennessee’s highest trust fund balance ever, both in total dollars and as a percent of total wages (Figure 7). (12)

Despite record balances, Tennessee fell just shy of a federal target for ability to weather a typical recession (Figure 7). Federal officials calculate recommended targets for each state based on their trust fund balances, total wages, and highest payouts in previous recessions. Going into 2020, Tennessee was among 21 states that had not met the recommended target. (58)

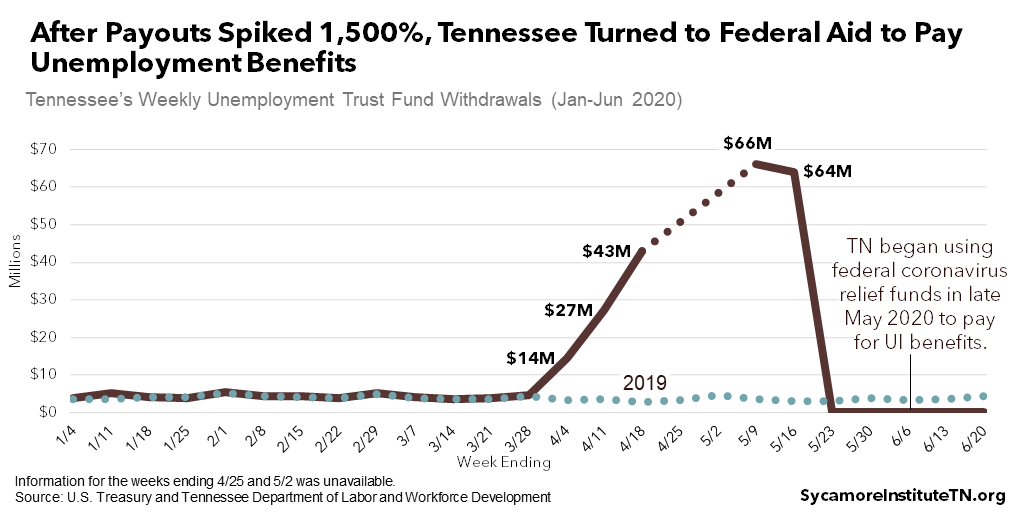

The recent historic influx of claims is expected to strain the state’s unemployment trust fund. Withdrawals from the trust fund began to spike the week ending April 4, 2020, rising to 15x normal levels by mid-May (Figure 8). Tennessee disbursed nearly $64 million in regular UI benefits from its trust fund the week ending May 16. Without factoring in new contributions, Tennessee’s estimated fund balance as of mid-May could support benefits at that level for about 14 weeks. (57) (1) (59) (60)

Figure 8

The state began using federal CARES Act money to pay out benefits in late May. (61) (62) (63) (2) The Lee administration plans to use a total of $400 million in FY 2020 from the state’s $2.4 billion federal Coronavirus Relief Fund allocation to backfill the state’s trust fund. The administration estimates that an additional $600 million would be needed between July and December to avoid an automatic rate increase on businesses under current state law. (64) (65)

Federal rules let states borrow to pay for unemployment benefits if their trust funds run out of money, though Tennessee’s balanced budget requirement limits the state’s ability to do so. (12) The CARES Act waives interest on state unemployment loans through the end of 2020. (66) Tennessee’s constitutional balanced budget requirement only allows the state to carry debt from one year to the next for projects with long-term value (e.g. capital). (67) (68) As a result, if the state were to take out a federal loan for its trust fund, it would have to pay it back within the same fiscal year.

*This report was updated shortly after publication to use more recent rankings for Tennessee’s wage replacement and recipiency rates. It was also updated on March 9, 2021 to correct information regarding waiting periods.

References

Click to Open/Close

- U.S. Department of Labor. Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims Data. [Online] May 1, 2020. [Cited: May 12, 2020.] https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/claims.asp.

- Tennessee Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Tennessee New Unemployment Claims: Week Ending on June 20, 2020. [Online] June 25, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/workforce/covid-19/news/2020/6/25/tennessee-new-unemployment-claims-filed.html.

- U.S. Department of Labor. Unemployment Compensation: Federal-State Partnership. Office of Unemployment Insurance, Division of Legislation. [Online] May 2019. https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/pdf/partnership.pdf.

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Policy Basics: Unemployment Insurance. [Online] April 1, 2020. https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/policy-basics-unemployment-insurance.

- State of Tennessee. Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-7-102 . [Online] [Cited: May 7, 2020.]

- Meyer, Bruce. Unemployment Insurance and Unemployment Spells. Econometrica. [Online] July 1990. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2938349?seq=1.

- Bradbury, Katharine. Labor Market Transitions and the Availability of Unemployment Insurance. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Working Papers. [Online] 2014. https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/research-department-working-paper/2014/labor-market-transitions-and-the-availability-of-unemployment-insurance.aspx.

- Chetty, Raj. Why do Unemployment Benefits Raise Unemployment Durations? Moral Hazard vs. Liquidity. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Papers. [Online] March 2006. https://www.nber.org/papers/w11760.

- Chodorow-Reich, Gabriel and Karabarbounis, Loukas. The Limited Macroeconomic Effects of Unemployment Benefit Extensions . National Bureau of Economic Research Working Papers. [Online] April 2016. https://www.nber.org/papers/w22163.

- Orrell, Brent. The Gordian Knot of Unemployment Benefits . American Enterprise Institute. [Online] April 23, 2020. https://www.aei.org/poverty-studies/the-gordian-knot-of-unemployment-benefits/.

- Tennessee Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Tennessee New Unemployment Claims Filed: Week Ending on May 2, 2020. [Online] May 7, 2020. [Cited: May 12, 2020.] https://www.tn.gov/workforce/covid-19/news/2020/5/7/tennessee-new-unemployment-claims-filed.html.

- U.S. Department of Labor. Unemployment Insurance Data. [Online] May 28, 2020. [Cited: June 10, 2020.] Accessed from https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/data_summary/DataSum.asp.

- —. UI Replacement Rate Reports. [Online] May 1, 2020. [Cited: June 11, 2020.] Accessed from https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/ui_replacement_rates.asp.

- —. Significant Provisions of State Unemployment Insurance Laws Effective January 2020. [Online] January 2020. [Cited: May 7, 2020.] https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/content/sigpros/2020-2029/January2020.pdf.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages – 2019 Fourth Quarter Average Weekly Wage, All Covered Employment, All Industries, All Establishment Sizes. [Online] January 2, 2020. Accessed from https://data.bls.gov/cew/apps/table_maker/v4/table_maker.htm#.

- U.S. Department of Labor. Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws as of January 1, 2019. [Online] [Cited: May 5, 2020.] https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/pdf/uilawcompar/2019/complete.pdf.

- State of Tennessee. Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-7-303 . [Online]

- —. Executive Order No. 15. [Online] March 19, 2020. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/pub/execorders/exec-orders-lee15.pdf.

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-7-218 . [Online]

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-7-301. [Online]

- Tennessee Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Do I Qualify for Unemployment Insurance? [Online] [Cited: May 5, 2020.] https://www.tn.gov/workforce/unemployment/apply-for-benefits-redirect-2/do-i-qualify.html.

- State of Tennessee. Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-7-302 . [Online]

- —. Public Chapter No. 824 (2012). [Online] April 25, 2012. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/107/pub/pc0824.pdf.

- —. Public Chapter No. 940 (2012). [Online] May 10, 2012. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/107/pub/pc0940.pdf.

- —. Public Chapter No. 3231 (2012). [Online] May 21, 2012. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/107/pub/pc1050.pdf.

- —. Public Chapter No. 427 (2013). [Online] May 16, 2013. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/108/pub/pc0427.pdf.

- —. Public Chapter No. 1063 (2016). https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/acts/109/pub/pc1063.pdf. [Online] May 20, 2016.

- Governor Bill Lee. Executive Order No. 36. [Online] May 12, 2020. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/pub/execorders/exec-orders-lee36.pdf.

- State of Tennessee. Executive Order No. 50. [Online] June 29, 2020. https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/pub/execorders/exec-orders-lee50.pdf.

- National Employment Law Project. Are State Unemployment Systems Still Able to Counter Recessions? [Online] June 2019. https://s27147.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/Data-Brief-State-Unemployment-Systems-Counter-Recession.pdf.

- Vroman, Wayne. Unemployment Insurance Recipients and Nonrecipients in the CPS. Monthy Labor Review. [Online] October 2009. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2009/10/art4full.pdf.

- Fitch Ratings. Coronavirus Causing Dramatic Differences in State Unemployment. [Online] May 7, 2020. https://www.fitchratings.com/research/us-public-finance/coronavirus-causing-dramatic-differences-in-state-unemployment-07-05-2020.

- Zipperer, Ben and Gould, Elise. Unemployment Filing Failures. Economic Policy Institute. [Online] April 28, 2020. https://www.epi.org/blog/unemployment-filing-failures-new-survey-confirms-that-millions-of-jobless-were-unable-to-file-an-unemployment-insurance-claim/.

- Stephenson, Cassandra. No Payments, No Answers and Weeks of Wait: For Some Tennesseans, Filing for Unemployment Has Been “a Disaster”. The Tennessean. [Online] April 29, 2020. https://www.tennessean.com/story/money/2020/04/30/tennessee-unemployment-filing-has-been-a-disaster/3003639001/.

- Tennessee Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Weekly Unemployment Certifications Move to Staggered Schedule . [Online] April 17, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/workforce/general-resources/news/2020/4/17/weekly-unemployment-certifications-move-to-staggered-schedule.html.

- —. Refusal to Work Could Jeopardize Unemployment Benefits. [Online] May 11, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/workforce/covid-19/news/2020/5/11/refusal-to-work-could-jeopardize-unemployment-benefits.html.

- Quinton, Sophie. Some States Let Vulnerable Workers Turn Down Jobs . Pew Stateline. [Online] May 6, 2020. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2020/05/06/some-states-let-vulnerable-workers-turn-down-jobs.

- Romm, Tony. Republican-Led States Signal They Could Strip Workers’ Unemployment Benefits If They Don’t Return to Work, Sparking Fresh Safety Fears. The Washington Post. [Online] April 30, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/04/30/republican-states-unemployment-benefits/.

- U.S. Department of Labor. Unemployment Insurance Relief During COVID-19 Outbreak: Frequently Asked Questions. [Online] [Cited: May 11, 2020.] https://www.dol.gov/coronavirus/unemployment-insurance#faqs.

- California Employment Development Department. COVID-19 FAQs: Unemployment Insurance Benefits . [Online] [Cited: June 29, 2020.] https://www.edd.ca.gov/about_edd/coronavirus-2019/faqs/unemployment.htm.

- Connecticut Department of Labor. Frequently Asked Questions About Coronavirus (COVID-19) for Workers and Employers. [Online] June 8, 2020. [Cited: June 29, 2020.] https://www.ctdol.state.ct.us/uiemployers.pdf.

- Vermont Department of Labor. Refusal to Return to Work: COVID-19. [Online] [Cited: June 29, 2020.] https://labor.vermont.gov/unemployment-insurance/refusal-return-work-covid-19.

- Michigan Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity. Suitale Work and Refusal to Work. [Online] [Cited: June 29, 2020.] https://www.michigan.gov/leo/0,5863,7-336-78421_97241_98585_100420—,00.html.

- State of Tennessee. Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-7-301. [Online]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Consumer Price Index: Total All Items for the United States (CPALTT01USQ661S) . [Online] [Cited: May 7, 2020.] Accessed from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis via https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPALTT01USQ661S, May 12, 2020..

- Pallasch, John. Unemployment Insurance Program Letter No. 14/20 – CARES Act Summary and Guidance. U.S. Department of Labor. [Online] April 2, 2020. https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/attach/UIPL/UIPL_14-20.pdf.

- State of Tennessee. Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-7-611 . [Online]

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-7-612 . [Online]

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-7-708 . [Online]

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-7-305 . [Online]

- Tennessee Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Unemployment Insurance Tax Rates. [Online] [Cited: May 7, 2020.] https://www.tn.gov/workforce/employers/tax-and-insurance-redirect/unemployment-insurance-tax/ui-tax-rates.html.

- —. Unemployment Insurance Tax. [Online] [Cited: May 7, 2020.] https://www.tn.gov/workforce/employers/tax-and-insurance-redirect/unemployment-insurance-tax.html.

- State of Tennessee. Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-7-205. [Online]

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-7-306 . [Online]

- Tennessee Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Premium Rate Chart for Nongovernmental Employers. [Online] [Cited: May 7, 2020.] https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/workforce/documents/employers/Premium_Rate_Chart.pdf.

- State of Tennessee. Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-7-403 . [Online]

- U.S. Treasury. Unemployment Trust Fund Report Selection. [Online] [Cited: June 26, 2020.] https://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/tfmp/tfmp_utf.htm.

- U.S. Department of Labor. State Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund Solvency Report 2020. [Online] February 2020. https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/docs/trustFundSolvReport2020.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Tennessee New Unemployment Claims Filed: Week Ending on May 9, 2020. [Online] May 14, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/workforce/covid-19/news/2020/5/14/tennessee-new-unemployment-claims-filed.html.

- —. Tennessee New Unemployment Claims Filed: Week Ending on May 23, 2020. [Online] May 28, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/workforce/covid-19/news/2020/5/28/tennessee-new-unemployment-claims-filed.html.

- —. Tennessee New Unemployment Claims Filed: Week Ending on May 30, 2020. [Online] June 4, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/workforce/covid-19/news/2020/6/4/tennessee-new-unemployment-claims-filed.html.

- Tennessee Deparment of Labor and Workforce Development. Tennessee New Unemployment Claims Filed: Week Ending on June 6, 2020. [Online] June 11, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/workforce/covid-19/news/2020/6/11/tennessee-new-unemployment-claims-filed.html.

- Tennessee Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Tennessee New Unemployment Claims Filed: Week Ending on June 13, 2020. [Online] June 18, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/workforce/covid-19/news/2020/6/18/tennessee-new-unemployment-claims-filed.html.

- Senate Finance, Ways, and Means Committee. Testimony from Butch Eley, TN Commissioner of Finance and Administration. [Online] May 28, 2020. Recorded video available at http://tnga.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=431&clip_id=23017.

- House Finance, Ways, and Means Committee. Testimony from Buth Eley, TN Commissioner of Finance and Administration. [Online] June 8, 2020. Recorded video available from http://tnga.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=460&clip_id=23134.

- Braun, Martin Z. State Unemployment Funds Going Broke From Flood of Claims . [Online] April 30, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-30/state-unemployment-funds-going-broke-from-record-flood-of-claims.

- State of Tennessee. Tennessee State Constitution, Article II, Section 24. [Online] http://www.capitol.tn.gov/about/docs/TN-Constitution.pdf.

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 9-9, Part 1. [Online]

Featured photo by Bytemarks