People who have medical debt or trouble paying their medical bills are more likely to have health issues — including high blood pressure, worse self-reported health status, poorer mental health, and shorter life expectancy. (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) While people with greater health needs require more care and are more likely to end up with large medical bills, the evidence suggests that medical debt itself can also affect our health.

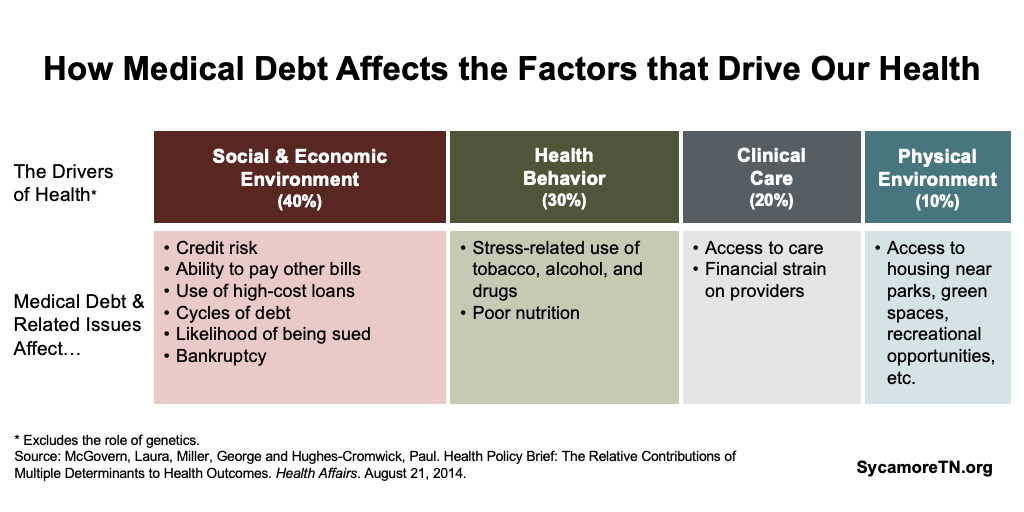

This report summarizes existing evidence on issues related to medical debt as a driver of health outcomes. Evidence for the drivers of health is well-established. Building on this body of work, we explore the connections between medical debt and health outcomes at the individual and population levels (Figure 1). Our review of the research looked at the effects of medical debt, the bills that can lead to it, and financial shocks and household debt more broadly.

Acknowledgment: This research was funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. We thank them for their support but acknowledge that the findings and conclusions presented in this report are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Foundation.

Sycamore takes a neutral and objective approach to analyze and explain public policy issues. Funders do not determine research findings. More information on our code of ethics is available here.

Figure 1

Our review suggests that medical debt itself may affect health outcomes, exacerbate already poor health outcomes, and worsen existing health disparities via:

- Adverse effects on both economic stability and mobility.

- Stress that affects mental health and, in some cases, prompts riskier health behaviors.

- Reduced use of and access to medical care.

- Limiting access to neighborhoods with built environments that foster good health.

The effects of medical debt can be long-lasting. Past-due medical bills reported to a credit bureau affect credit history for seven years. (6) Debts can also be bought and sold multiple times over the course of many years. (7) These debt buyers and collectors often tack on additional charges and take legal actions – both of which can exacerbate and prolong the effects of medical debt.

Effects on Economic Opportunity

Medical debt has negative effects on people’s economic circumstances and can make it harder to stay afloat or get ahead.

Impact on Credit History

Medical debt hurts your credit history and credit scores. (8) (9) A creditor (i.e. a health care provider) or debt collector can report an unpaid medical bill to credit bureaus at any point after the bill is issued. (10) If you do not pay the bill within 180 days of that report, the debt appears on your credit report as an “account in collections.” (11) Once reported, your credit score is reduced for seven years — even if you ultimately pay off the debt (Note: It can be removed immediately if an insurer pays it). (6) While consumers can usually improve their credit scores by making on-time debt payments (e.g. for a mortgage or credit cards), credit bureaus do not track on-time medical bill payments. As a result, medical bills can reduce your credit score but cannot improve it. (12) (13)

Credit scores have a wide-range of uses that affect the drivers of health — including housing, employment, access to transportation, and the ability to access the type of credit that helps build wealth. Lenders use credit scores in a number of ways to gauge an individual’s liabilities and the probability that they will pay their financial obligations:

- Access to “Good” Debt — Lower credit scores can make it harder to access the types of loans and credit that can enhance economic mobility and long-term wealth (e.g. home loans). (14) (15) (16)

- Employment — Many employers check credit reports when making hiring and promotion decisions. (17) A 2017 national survey of employers found that over 30% checked credit history in making employment decisions. (18) Some evidence, however, calls into question the extent to which employers rely on credit scores alone. (16)

- Housing — Credit scores can determine a person’s ability to secure a mortgage as well as the terms of their loan. In addition, landlords often check potential tenants’ credit reports, and they may reject applicants for poor credit history or require a larger security deposit. (17)

- The Cost of Debt — A good credit score helps people qualify for loans with lower interest rates. In August 2018, a person with good credit could have paid $3,000 less in interest on a $10,000 car loan than someone with a poor credit score. (19)

- Transportation & Utilities — Credit history can also affect basic needs like transportation and utilities. Car loans can be more expensive or unattainable for those with poor credit, and utility companies (e.g. water, electricity, internet, cable) may require larger security deposits from new customers with poor credit. (17)

- Insurance Premiums — Credit history can also affect home, auto, and life insurance premiums. (20) (21)

Medical debt, however, does not always accurately reflect one’s will or ability to pay. (12) (22) A 2014 study by the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau found that half of people with medical collections had an otherwise clean credit history. (23) One reason may be bills sent to collections for reasons other than willingness or ability to pay (e.g. a surprise bill or as a result of the complexities of medical billing). As a result, some entities that evaluate credit information (e.g. credit bureaus, lenders, employers) now exclude medical collections when reviewing credit histories. (12) (22) However, excluding medical debt is not a required or widespread practice.

Diverted Resources

Those who lack the resources to pay unexpected medical bills may spend down their savings or divert funding from other bills and expenses. (14) (24) (1) (9) People with large medical bills and medical debt, for example, report difficulty paying other bills and meeting basic needs. They may have problems paying for food, housing, clothing, and utilities. (1) (25) (26)

Other Debts

Financial shocks like an unaffordable medical expense may lead people to use higher-cost financing methods like credit cards or high-cost loans. (14) (24) (1) (27) (28) (29) (30) (9) For example, a 2016 Kaiser Family Foundation national survey found that 34% of people who reported problems paying medical bills increased credit card debt to help pay them. (1)

The evidence on the effects of alternative financial products is mixed. These products include services provided outside federally-insured banks — such as money orders, check cashing, payday lending, flex loans, and tax refund loans. People rely on these services to not only fill income gaps or pay for unexpected expenses like medical bills but also to pay for ongoing expenses. (28) Some evidence suggests that their use is associated with reduced ability to meet basic needs, poor health outcomes, and financial insecurity. (31) Other studies suggest they may have neither a negative nor positive effect on measures of financial well-being. (32)

Cycles of Debt

Financially troublesome medical bills and medical debt may lead to or prolong cycles of debt. People who face problems paying medical bills are more likely to have credit card debt, student loans, car loans, mortgages, and payday loans (i.e. a short-term, high-interest unsecured loan). (1) (33) (34) In some cases, a single medical bill brought on by an unexpected event may be the first of many that also makes it harder to pay off other types of debt. (34)

Lawsuits

Individuals with medical debt may ultimately face lawsuits that exacerbate the negative economic effects of debt. Like all creditors, health care providers and debt collectors are allowed to sue people in civil court for unpaid bills. A growing number of studies and media reports suggest that medical debt lawsuits are common in Tennessee and other areas of the country. (35) (36) (37) (38) (39) (40) (41) (42) (43)

Most debt lawsuits go unchallenged. In a 2015 CFPB survey, about 15% of Americans contacted by a debt collector in the past year reported being sued. Of those, only about 26% attended the court proceeding. (44) Some reasons people may not attend include lack of notice or legal representation, receiving incorrect or misleading information, confusion about the alleged debt, and income, job, or travel constraints. (7) (45) When people don’t show up, courts often issue default judgments. (7)

Lawsuits can inflate the costs of the original debt by tacking on court costs, attorney’s fees, and interest. Collectors can use a number of tools to recoup settlements, including garnishing wages and seizing assets. (7) (45) Wage garnishments effectively reduce income, and the seizure of a vehicle, tools, or equipment could make it harder for individuals to work. In the some scenarios, even a home could be seized to pay down a debt. (46)

Bankruptcies

People with medical debt are more likely to file for bankruptcy. People file for bankruptcy for multiple reasons, and the extent to which medical debt causes bankruptcy is disputed. (47) (48) However, multiple studies suggest that medical debt is often a major contributor in consumer bankruptcies. (49) (9) (50)

Effects on Health Behaviors

Medical debt negatively influences health behaviors. Debt and debt-related collections practices can cause stress that can lead to risky health behaviors like smoking, increased alcohol consumption, and poor nutrition. (51) Some collectors reportedly use threats of legal action and jail time as an intimidation tactic, even when there may be no legal basis for a lawsuit. (7) These and other aggressive debt collection practices — garnishing wages, property liens, and home foreclosures — can further increase stress. (52) (53)

Effects on Clinical Care

Medical debt negatively impacts access to and utilization of needed health care — at both the individual and community level.

Individual Utilization and Access

People with medical debt and other forms of debt are less likely to access needed health care or prescriptions than those without. (54) (55) (56) (2) (1) (57) (58) Potential reasons can include being hesitant to incur additional debt or providers refusing service until past-due bills are paid. (24)

Community Access

The bad debt that arises from medical debt can threaten the financial viability of local health care providers. Most hospitals that close do so because of financial problems. The causes of financial problems are often multi-dimensional, but high levels of uncompensated care and bad debt can put financial strain on hospitals — particularly for rural facilities that have a less profitable mix of payers and face a number of other negative pressures (e.g. demographics, low utilization, technology, etc.). (59) (60) (61) (62) (63) This can contribute to hospital closures that affect entire communities — not just the local residents with medical debt.

Effects on the Physical Environment

Medical debt can create barriers to financial security and homeownership that limit access to neighborhoods with built environments that foster good health. Higher-income, higher-cost neighborhoods and those with more owner-occupied homes tend to offer better access to parks, green spaces, and community recreational opportunities and supervised programming. (64) (65) (66) (67) (68) (69) (70) Meanwhile, the construction of new parks, greenways, and green spaces in low-income neighborhoods can boost local property values – which may or may not affect who can afford to live there. (71) (72) (73)

Effects on Health Disparities

Available information suggests that medical debt may worsen existing racial and socioeconomic disparities in health security. Populations that experience health disparities — typically black and Hispanic Americans and people with less income and education — are more likely to have medical debt. (1) (57) (74) (43) Communities with a larger share of non-white residents and those with lower incomes are also more likely to have higher rates of medical debt. (75)

For financially fragile households already facing issues that contribute to health disparities, medical bills they can’t afford may be a tipping point. In fact, evidence suggests that the negative effects of medical debt for these populations may be worse than for other populations. For example:

- Low-income households may be more susceptible to bankruptcy resulting from medical debt. (33) (34)

- Debtors who are black may face more lawsuits. (76)

- Uninsured individuals with lower incomes may be likelier to face more aggressive debt collection practices. (52) (53)

- The effects of stress may be more pronounced for Americans who are black, Hispanic, or have low socioeconomic status. (77)

Conclusion

A growing body of evidence connects medical debt with health outcomes through effects that we already know influence health. Medical debt-specific research and existing research on the drivers of health draw a clear link between these factors and poorer health outcomes. Even when poor health itself contributes to medical debt, debt-related issues can exacerbate the situation and worsen existing health disparities. Like all other drivers of health, the effects of medical debt are closely interrelated and mutually influential (e.g. the health effects of medical debt may intensify economic stability issues by leading to lower productivity).

*This paper was updated on March 26, 2024 to correct a mistake in Figure 1.

References

Click to Open/Close

- Hamel, Liz, et al. The Burden of Medical Debt: Results from the Kaiser Family Foundation/New York Times Medical Bills Survey. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Online] January 2016. [Cited: December 4, 2018.] https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/8806-the-burden-of-medical-debt-results-from-the-kaiser-family-foundation-new-york-times-medical-bills-survey.pdf.

- Herman, Patricia M, Rissi, Jill J and Walsh, Michele E. Health Insurance Status, Medical Debt, and Their Impact on Access to Care in Arizona. American Journal of Public Health, 101(8): 1437-1443. [Online] 2011. [Cited: December 5, 2018.] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3134508/.

- Rahimi, Ali R, Spertus, John A and Reid, Kimberly J. Financial Barriers to Health Care and Outcomes After Acute Myocardial Infarction. jama, 297(10): 1063-1072. [Online] March 14, 2007. [Cited: December 11, 2018.] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/206020.

- Sweet, Elizabeth, et al. The High Price of Debt: Household Financial Debt and Its Impact on Mental and Physical Health. Social Science and Medicine, 91: 94-100. [Online] August 2013. [Cited: November 18, 2018.] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3718010/.

- Clayton, Maya, Liñares-Zegarra, José and Wilson, John O.S. Can Debt Affect Your Health? Cross Country Evidence on the Debt-Health Nexus. [Online] April 2014. [Cited: December 11, 2018.] https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2429025.

- Richardson, Thomas and Roberts, Ron. The Relationship between Personal Unsecured Debt and Mental and Physical Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(8): 1148-1162. [Online] December 2013. [Cited: December 11, 2018.] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272735813001256.

- Stifler, Lisa and Parrish, Leslie. Debt Collection & Debt Buying. Center for Responsible Lending. [Online] April 2014. https://www.responsiblelending.org/state-of-lending/reports/11-Debt-Collection.pdf.

- Brevoort, Kenneth and Kambara, Michelle. Data Point: Medical Debt and Credit Scores. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. [Online] May 2014. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201405_cfpb_report_data-point_medical-debt-credit-scores.pdf.

- Collins, Sara, Gunja, Munira and Doty, Michelle. How Well Does Insurance Coverage Protect Consumers from Health Care Costs? The Commonwealth Fund. [Online] October 18, 2017. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2017/oct/how-well-does-insurance-coverage-protect-consumers-health-care.

- Stone, Corey. Here’s How Medical Debt Hurts Your Credit Score. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. [Online] December 11, 2014. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/blog/heres-how-medical-debt-hurts-your-credit-report/.

- Andrews, Michelle. Medical Debt? Big Changes are Coming to the Way Credit Agencies Report It. Kaiser Health News. [Online] July 2017. [Cited: January 30, 2019.] https://www.statnews.com/2017/07/11/credit-score-medical-debt/.

- Rukavina, Mark. Medical Debt and Its Relevance When Assessing Creditworthiness. Suffole University Law Review. [Online] January 2014. http://suffolklawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Rukavina_Lead.pdf.

- Wu, Chi Chi. Strong Medicine Needed: What the CFPB Should Do to Protect Consumers from Unfair Collection and Reporting of Medical Debt. National Consumer Law Center. [Online] September 2014. [Cited: December 4, 2018.] http://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/pr-reports/report-strong-medicine-needed.pdf.

- Seifert, Robert W and Rukanina, Mark. Bankruptcy Is the Tip of a Medical-Debt Iceberg. Health Affairs, 25(2): W89-W92. [Online] 2006. [Cited: December 11, 2018.] https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.25.w89.

- Expanding Prosperity Impact Collaborative (EPIC). Consumer Debt: A Primer. The Aspen Institute. [Online] March 2018. [Cited: December 11, 2018.] http://www.aspenepic.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Consumer-Debt-Primer.pdf.

- Dobbie, Will, et al. Bad Credit, No Problem? Credit and Labor Market Consequences of Bad Credit Reports. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Online] October 2016. https://www.nber.org/papers/w22711.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Consumer’s Guide: Credit Reports and Credit Scores. [Online] [Cited: February 4, 2019.] https://www.federalreserve.gov/creditreports/pdf/credit_reports_scores_2.pdf.

- HR.com. National Survey: Employers Universally Use Background Checks to Protect Employees, Customers, and the Public. National Association of Professional Background Screeners. [Online] June 2017. https://pubs.napbs.com/pub.cfm?id=6E232E17-B749-6287-0E86-95568FA599D1.

- Elliot, Diana and Lowitz, Ricki Granetz. What is the Cost of Poor Credit? Urban Institute. [Online] September 2018. [Cited: January 28, 2019.] https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/99021/what_is_the_cost_of_poor_credit_1.pdf.

- Commissioners, National Association of Insurance. Credit-Based Insurance Scores: How An Insurance Company Can Use Your Credit to Deterimine Your Premium. [Online] June 2012. https://www.naic.org/documents/consumer_alert_credit_based_insurance_scores.htm.

- State of Tennessee. TN Code § 56-5-202(3)(E) (2017). [Online] https://law.justia.com/codes/tennessee/2017/title-56/chapter-5/part-2/section-56-5-202/.

- Avery, Robert B, Calem, Paul S and Canner, Glenn B. Credit Report Accuracy and Access to Credit. Federal Reserve Bulletin. [Online] Summer 2004. https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/bulletin/2004/summer04_credit.pdf.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Consumer Credit Reports: A Study of Medical and Non-Medical Collections. [Online] December 2014. [Cited: November 18, 2018.] https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201412_cfpb_reports_consumer-credit-medical-and-non-medical-collections.pdf.

- Pollitz, Karen and Cox, Cynthia. Medical Debt Among People with Health Insurance. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Online] January 7, 2014. https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/report/medical-debt-among-people-with-health-insurance/.

- Gallagher, Emily, Gopalan, Radhakrishnan and Grinstein-Weiss, Michal. The Effect of Health Insurance on Home Payment Delinquency: Evidence from ACA Marketplace Subsidies. Journal of Public Economics 172: 67-83. [Online] April 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.12.007.

- Robertson, Christopher Tarver, Egelhof, Richard and Hoke, Michael. Get Sick, Get Out: The Medical Causes for Home Mortgage Foreclosures. Health Matrix: The Journal of Law-Medicine, 18(1):. [Online] 2008. [Cited: November 18, 2018.] https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/healthmatrix/vol18/iss1/4/.

- Allen, Heidi, et al. Early Medicaid Expansion Associated With Reduced Payday Borrowing In California. Health Affairs 36(10). [Online] October 2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0369.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts. Pay Day Lending in America: Who Borrows, Where They Borrow, and Why. [Online] July 2012. https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2012/pewpaydaylendingreportpdf.pdf.

- Lusardi, Annamaria, Schneider, Daniel and Tufano, Peter. Financially Fragile Households: Evidence and Implications. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Online] May 2011. https://www.nber.org/papers/w17072.pdf.

- Bickham, Trey and Lim, Younghee. In Sickness and in Debt: Do Mounting Medical Bills Predict Payday Loan Debt? Social Work in Health Care 54(6). [Online] July 17, 2015. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00981389.2015.1038410?journalCode=wshc20.

- Eisenberg-Guyot, Jerzy, et al. From Payday Loans To Pawnshops:Fringe Banking, The Unbanked, and Health. Health Affairs, 3 (2018): 429-437. [Online] 2018. [Cited: May 30, 2019.] https://csde.washington.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Eisenberg-Guyot-2018-payday-loans-health.pdf.

- Bhutta, Neil, Marta Skiba, Paige and Tobacman, Jeremy. Payday Loan Choices and Consequences. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 47(2-3): 223-260. [Online] March 27, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmcb.12175.

- Karpman, Michael and Caswell, Kyle J. Past-Due Medical Debt Among Nonelderly Adults, 2012–15. Urban Institute. [Online] 2017. [Cited: December 12, 2018.] https://www.urban.org/research/publication/past-due-medical-debt-among-nonelderly-adults-2012-15.

- Gross, Tal and Notowidigdo, Matthew J. Health Insurance and the Consumer Bankruptcy Decision: Evidence from Expansions of Medicaid. Journal of Public Economics, 95: 767-778. [Online] 2011. [Cited: December 11, 2018.] http://isiarticles.com/bundles/Article/pre/pdf/48303.pdf.

- Bruhn, William, Rutkow, Lainie and Wang, Peiqi. Prevalence and Characteristics of Virginia Hospitals Suing Patients and Garnishing Wages for Unpaid Medical Bills. Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). [Online] June 25, 2019. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2737183?guestAccessKey=53054006-0692-44bc-86ea-f001bef3f1f3.

- Thomas, Wendi C. A Tennessee Hospital Sues Its Own Employees When They Can’t Pay Their Medical Bills. NPR. [Online] June 28, 2019. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/06/28/736736444/a-tennessee-hospital-sues-its-own-employees-when-they-cant-pay-their-medical-bil.

- Arnold, Chris. When Nonprofit Hospitals Sue Their Poorest Patients. NPR. [Online] December 19, 2014. https://www.npr.org/2014/12/19/371202059/when-a-hospital-bill-becomes-a-decade-long-pay-cut.

- Simmons-Duffin, Selena. When Hospitals Sue For Unpaid Bills, It Can Be ‘Ruinous’ For Patients. NPR. [Online] June 25, 2019. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/06/25/735385283/hospitals-earn-little-from-suing-for-unpaid-bills-for-patients-it-can-be-ruinous.

- Thomas, Wendi. The Nonprofit Hospital That Makes Millions, Owns a Collection Agency and Relentlessly Sues the Poor. ProPublica. [Online] June 27, 2019. https://www.propublica.org/article/methodist-le-bonheur-healthcare-sues-poor-medical-debt.

- Armour, Stephanie. When Patients Can’t Pay, Many Hospitals Are Suing. The Wall Street Journal. [Online] June 25, 2019. https://www.wsj.com/articles/nonprofit-hospitals-criticized-for-debt-collection-tactics-11561467600.

- AFL-CIO, National Nurses United, and Coalition for a Humane Hopkins. Taking Neighbors to Court: John Hopkins Hospital Medical Debt Lawsuits. [Online] May 2019. https://act.nationalnursesunited.org/page/-/files/graphics/Johns-Hopkins-Medical-Debt-report.pdf.

- Pellegrin, Mandy and Melton, Courtnee. Medical Debt in Tennessee: 12 Options for State Policymakers. The Sycamore Institute. [Online] October 15, 2019. https://www.sycamoreinstitutetn.org/medical-debt-policy-options/.

- Villagra, Victor, et al. When Hospitals and Doctors Sue Their Patients: The Medical Debt Crisis Through A New Lens. UConn Health Disparities Institute. [Online] June 2019. https://health.uconn.edu/health-disparities/wp-content/uploads/sites/53/2019/06/HDI-Issue-Brief_When-Hospitals-and-Doctors-Sue-Their-Patients.pdf.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Consumer Experiences with Debt Collection: Findings from the CFPB’s Survey of Consumer Views on Debt. [Online] 2017. https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/201701_cfpb_Debt-Collection-Survey-Report.pdf.

- Lieberman, Hannah E. M. and Hannaford-Agor, Paula. Meeting the Challenges of High-Volume Civil Dockets. National Center for State Courts. [Online] February 2016. https://www.ncsc.org/~/media/Microsites/Files/Trends%202016/Meeting-the-Challenges.ashx.

- Carter, Carolyn. No Fresh Start in 2019: How State Still Allow Debt Collectors to Push Families Into Poverty. National Consumer Law Center. [Online] November 2019. https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/debt_collection/rpt-no-fresh-start-bw-nov2019.pdf.

- Dobkin, Carlos, et al. Myth and Measurement — The Case of Medical Bankruptcies. New England Journal of Medicine 378(12): 1076-1078. [Online] March 2018. http://economics.mit.edu/files/14892.

- Mathur, Aparna. Exposing the Myth of Widespread Medical Bankruptcies. Forbes. [Online] April 9, 2018. https://www.forbes.com/sites/aparnamathur/2018/04/09/exposing-the-myth-of-widespread-medical-bankruptcies/#5098b1e7c2a1.

- Austin, Daniel A. Medical Debt as a Cause of Consumer Bankruptcy. Maine Law Review, 67(1): 1-23. [Online] 2014. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2515321.

- Himmelstein, David, et al. Medical Bankruptcy: Still Common Despite the Affordable Care Act. American Journal of Public Health 109(3): 431-433. [Online] March 2019. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304901.

- Drentea, Patricia and Lavrakas, Paul J. Over the Limit: the Association among Health, Race and Debt. Social Science & Medicine, 50: 517-529. [Online] 2000. [Cited: December 11, 2018.] http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.410.5751&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- O’Teele, Thomas P, Arbelaes, Jose J and Lawrence, Robert S. Medical Debt and Aggressive Debt Restitution Practices: Predatory Billing Among the Urban Poor. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19(7): 772-778. [Online] July 2004. [Cited: December 4, 2018.] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1492479/.

- Jacoby, B Melissa and Warren, Elizabeth. Beyond Hospital Misbehavior: An Alternative Account of Medical-Related Financial Distress. Northwestern University Law Review. [Online] 2006. [Cited: April 8, 2019.] https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1147&context=faculty_publications.

- Kalousova, Lucie and Burgard, Sarah A. Debt and Foregone Medical Care. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 54(2): 204-220. [Online] 2013. [Cited: November 18, 2018.] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0022146513483772.

- Lessard, Laura and Solomon, Julie. Demographic and Service-Use Profiles of Individuals Using the CarePayment Program for Hospital-Related Medical Debt: Results from a Nationwide Survey of Guarantors. BMC Health Services Research, 16:264. [Online] 2016. [Cited: December 5, 2018.] https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-016-1525-0.

- Kalousova, Lucie and Burgard, Sarah A. Tough Choices in Tough Times: Debt and Medication Nonadherence. Health Education & Behavior, 41(2): 155-163. [Online] 2014. [Cited: December 5, 2018.] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1090198113493093.

- Lin, Judy, et al. The State of U.S. Financial Capability: The 2018 National Financial Capability Study. FINFRA Investor Education Foundation. [Online] June 2019. https://www.usfinancialcapability.org/downloads/NFCS_2018_Report_Natl_Findings.pdf.

- Collins, Sara, Bhupal, Herman and Doty, Michelle. Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA. The Commonwealth Fund. [Online] February 7, 2019. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2019/feb/health-insurance-coverage-eight-years-after-aca.

- NC Rural Health Research Program. Rural Hospital Closures: More Informaiton. UNC Sheps Center for Health Services Research. [Online] [Cited: February 24, 2020.] https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures/rural-hospital-closures/.

- Pink, George, et al. Geographic Variation in the 2016 Profitability of Urban and Rural Hospitals. NC Rural Health Research Program. [Online] March 2018. https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2018/03/Geographic-Variation-2016-Profitability-of-Rural-Hospitals.pdf.

- Reiter, Kristin, Noles, Marissa and Pink, George. Uncompensated Care Burden May Mean Financial Vulnerability For Rural Hospitals In States That Did Not Expand Medicaid. Health Affairs 34(10). [Online] October 2015. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1340.

- Lindrooth, Richard, et al. Understanding The Relationship Between Medicaid Expansions And Hospital Closures. Health Affairs 37(1). [Online] January 2018. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0976.

- Thompson, Kristie, et al. Does ACA Insurance Coverage Expansion Improve the Financial Performance of Rural Hospitals? NC Rural Health Research Program. [Online] June 2016. https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2016/04/Effects-of-ACA-on-Uncompensated-Care-1.pdf.

- Herbert, Christopher E, Rieger, Shannon and Spader, Jonathan. Expanding Access to Homeownership as a Means of Fostering Residiential Integration and Inclusion. Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. [Online] https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/a_shared_future_expanding_access_to_homeownership_fostering_inclusion.pdf.

- Babey, Susan H., Hastert, Theresa A. and Brown, E. Richard. Teens Living in Disadvantaged Neighborhoods Lack Access to Parks and Get Less Physical Activity. UCLA Health Policy Research Brief. [Online] March 2007. http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/publications/Documents/PDF/Teens%20Living%20in%20Disadvantaged%20Neighborhoods%20Lack%20Access%20to%20Parks%20and%20Get%20Less%20Physical%20Activity.pdf.

- McKenzie, Thomas L., et al. Neighborhood Income Matters: Disparities in Community Recreation Facilities, Amenities, and Programs. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration. [Online] Winter 2013. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4082954/.

- Dai, Dajun. Racial/Ethnic and Socioeconomic Disparities in Urban Green Space Accessibility: Where to Intervene. Landscape and Urban Planning. [Online] September 30, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.05.002.

- Moore, Latetia V., et al. Availability of Recreational Resources in Minority and Low Socioeconomic Status Areas. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. [Online] January 2008. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.amepre.2007.09.021.

- Cohen, Deborah, et al. The First National Study of Neighborhood Parks. American Journal of Preventive Medicine / RAND Corporation. [Online] May 2016. https://www.rand.org/pubs/external_publications/EP66493.html.

- Rigolon, Alessandro, Browning, Matthew and Jennings, Viniece. Inequities in the Quality of Urban Park Systems: An Environmental Justice Investigation of Cities in the United States. Landscape and Urban Planning. [Online] 2018. https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/ja/2018/ja_2018_jennings_003.pdf.

- Rigolon, Alessandro and Nemeth, Jeremy. When Do New Parks Drive Gentrification? Uran Studies Journal. [Online] December 18, 2019. https://housingmatters.urban.org/research-summary/when-do-new-parks-drive-gentrification.

- —. “We’re Not in the Business of Housing:” Environmental Gentrification and the Nonprofitization of Green Infrastructure Projects. Cities. [Online] November 2018. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0264275117314749?via%3Dihub.

- Brummet, Quentin and Reed, Davin. The Effects of Gentrification on the Well-Being and Opportunity of Original Resident Adults and Children. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. [Online] July 2019. https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/research-and-data/publications/working-papers/2019/wp19-30.pdf.

- Wiltshire, Jacqueline, et al. Medical Debt and Related Financial Consequences Among Older African American and White Adults. American Journal of Public Health 106(6): 1086-1091. [Online] June 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4880274/.

- Braga, Breno, McKernan, Signe-Mary and Quakenbush, Caleb. Debt in America: An Interactive Map. The Urban Institute. [Online] December 17, 2019. https://apps.urban.org/features/debt-interactive-map/?type=overall&variable=median_debt_in_collections.

- Lichtenstein, B and Weber, J. Losing Ground: Racial Disparities in Medical Debt and Home Foreclosure in the Deep South. Family Community Health 39(3): 178-87. [Online] July 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27214673.

- American Psychological Association. Stress and Health Disparities: Contexts, Mechanisms, and Intervensions Among Racial/Ethnic Minority and Low Socioeconomic Status Populations. [Online] 2017. https://www.apa.org/pi/health-disparities/resources/stress-report.pdf.

- Braga, Breno, et al. Local Conditions and Debt in Collections. Urban Institute. [Online] June 2016. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/81886/2000841-Local-Conditions-and-Debt-in-Collections.pdf.