Key Takeaways

- The Trump administration has opened the door to letting states require some Medicaid enrollees to work or engage in work-related activities.

- Medicaid work requirements would most likely affect non-elderly adults without disabilities.

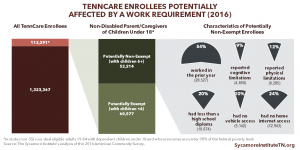

- According to Census data, an estimated 168,000 non-elderly adults enrolled in TennCare in 2016 did not work for reasons other than health or disability. Of these, 99,000 were caregivers or in school.

- Self-reported Census data offer a general sense of who might be affected but may be insufficient for designing a work requirement.

What Are Medicaid Work Requirements?

“Medicaid work requirements” broadly refer to requiring able-bodied adults enrolled in Medicaid to either work or participate in activities like job training, job search, school attendance, or community service.

A number of public assistance programs have work requirements, including Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and federal housing rental assistance. These “welfare-to-work programs” aim to transition enrollees from public assistance to self-sufficiency through participation in the labor market. Recently, federal and state policymakers have shown interest in adding work requirements to Medicaid (i.e. TennCare).

This report examines recent proposals, their policy rationale, and publicly available data on the populations most likely to be affected. Part 2 in this series will analyze Tennessee’s welfare-to-work experience, and Part 3 will summarize key points to consider for a potential TennCare work requirement. Together, these reports seek to help interested parties weigh the trade-offs of a Medicaid work requirement. Get the whole 3-part series here.

Federal Interest in Tying Medicaid Benefits to Work

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and Congress have both shown interest in 2017 in letting states establish Medicaid work requirements.

Interest from HHS

Previous administrations have not approved mandatory work-related activities for state Medicaid programs, but a recent letter from the Trump administration has opened the door for that to change. Under previous presidents, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has, in limited circumstances, let state Medicaid programs incorporate voluntary or incentivized work-related activities like job search and referral services. To date, they have not approved any proposals to require work-related activities — arguing they are outside the scope of Medicaid’s statutory purpose.

However, a 2017 letter to state governors from HHS Secretary Tom Price expressed intent to “approve meritorious innovations that build on the human dignity that comes with training, employment, and independence.” (1) The limits of what HHS could approve under current federal law are unclear. Within HHS, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has formal jurisdiction over states’ proposals.

Interest from Congress

Two major bills in Congress would grant states explicit authority to make certain populations’ Medicaid eligibility contingent on meeting work requirements. Under the American Health Care Act passed by the U.S. House and the Better Care Reconciliation Act proposed in the Senate, work requirements could apply to all adults except those who are disabled, elderly, or pregnant.

Work activities could include paid and unpaid employment, vocational training, and educational activities. States could define the number of hours of work activity required each week, the length of any “grace period” before requirements must be met, and at what point enrollees would lose benefits for not meeting requirements. (2) (3)

States’ Interest in Tying Medicaid Benefits to Work

States’ interest in Medicaid work requirements is primarily in the context of Medicaid expansion. Other states’ proposals to date range from requiring work as a condition of eligibility for all Medicaid enrollees to offering voluntary job placement/training services only to adults made Medicaid-eligible under the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) expansion.

As of May 31, 2017, 12 states had or were planning to propose work requirements for their state Medicaid programs — including 9 with work as a condition of eligibility.

- 4 proposals (AZ, IN, NH, OH) have been rejected by CMS

- 6 proposals (AZ, AK, FL, ME, UT, WI) are still in development at the state level

- 3 voluntary job placement/training components (IN, MT, PA) have been approved by CMS

- 1 proposal (KY) is under review by CMS (4)

The Commonwealth Fund has a breakdown of each state’s proposal, the details of which vary significantly.

Why Is There Interest in Medicaid Work Requirements?

A common argument in favor of work requirements is that recipients of public assistance who are able to work should work. With Medicaid specifically, some policymakers are concerned that the ACA’s expansion of eligibility to able-bodied adults discourages work.

Prior to the ACA, Medicaid eligibility was largely limited to low-income individuals who are pregnant, have a disability, or are children or seniors. Post-ACA, many states have expanded Medicaid to low-income, non-disabled adults without children. Some policymakers believe that individuals otherwise capable of working may be incentivized to decrease their work hours or leave the workforce in order to receive Medicaid. (See the Text Box at the bottom of the page).

Research on Medicaid and the Labor Market

Research on the impact of Medicaid on labor market outcomes is mixed. Some research has found that Medicaid creates a disincentive to work, while other studies have found a positive or neutral effect on labor market outcomes. (5) (6) Studies have found:

- Following Tennessee’s 2005 rollback of the 1994 TennCare expansion, there was a “sudden” increase in employment and job searches among childless adults (controlling for larger labor market trends). (7)

- A Medicaid eligibility expansion in Oregon in 2008 did not have a statistically significant effect on enrollees’ individual earnings or employment. (8)

- When Wisconsin suspended enrollment under a 2009 Medicaid expansion, employment among childless adult enrollees fell by roughly 2 to 10 percentage points compared to adults who were waitlisted. (5)

Following the ACA’s Medicaid expansion in 2014, low-income adults in Medicaid expansion states were no more likely to become unemployed, switch jobs, or switch from full-time to part-time work than low-income adults in non-expansion states. (9) There was also no significant difference in part-time and full-time employment rates between ACA Medicaid expansion states and non-expansion states. (10)

Who Are Work Requirements Likely to Impact in Tennessee?

Medicaid work requirements are most likely to affect non-elderly adults without disabilities. Tennessee has not opted into the ACA’s optional Medicaid eligibility expansion, so childless adults without disabilities are largely ineligible for TennCare. TennCare primarily serves low-income individuals in one of the following categories: children, pregnant women, parents and caregiver relatives, seniors, individuals with disabilities, or individuals in need of a level of care traditionally provided in a nursing home. As a result, TennCare covers fewer non-elderly, non-disabled adults than the national average. In 2014, 22% of full-benefit TennCare enrollees were adults without disabilities, versus 28% nationally. [i] (11)*

Detailed data on the work status of non-elderly, non-disabled adults covered by TennCare are unavailable. However, U.S. Census Bureau data on non-elderly, adult TennCare enrollees (including those with disabilities) offer some insight into the size and work status of the current TennCare population that a work requirement might affect.

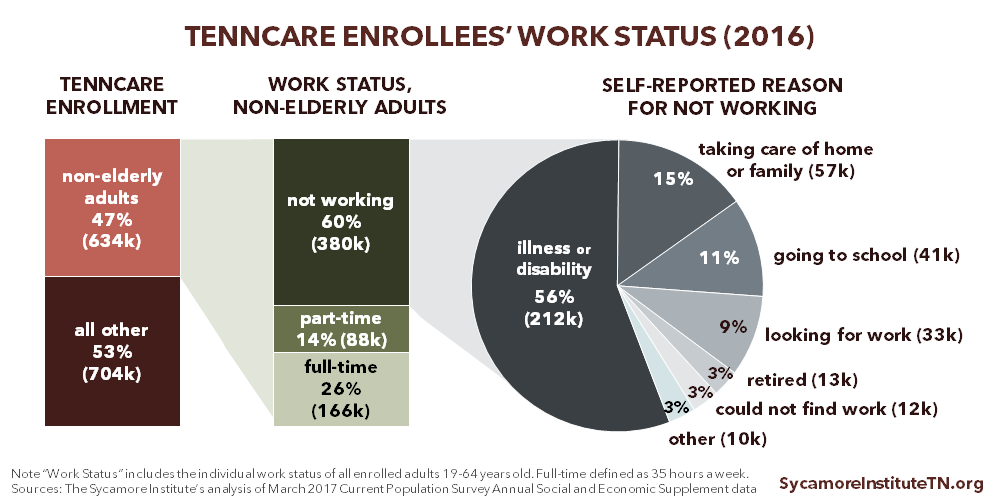

Figure 1

Our Findings

About 380,000 non-elderly, adult TennCare enrollees told the Census Bureau they did not work in 2016, with the most common reason (56%) being illness or disability (Figure 1). Of the non-elderly, adult enrollees (defined as 18 to 64 years old) who were not working:

- 56% (212,000) reported having a health problem or disability that limited their ability to work.

- 15% (57,000) reported that they did not work because they were taking care of home or family.

- 11% (41,000) reported being in school.

- 9% (33,000) reported actively looking for work.

- 3% (13,000) reported being retired.

- 3% (12,000) reported being unable to find work.

- 3% (10,000) did not specify a reason.

Limitations of the Data

There are limitations to using this data from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS) to analyze TennCare enrollees’ work status and the potential effect of a work requirement:

- The CPS data show total TennCare 2016 enrollment at 1.3 million. TennCare itself reports enrollment of 1.6 million in December 2016. (12)

- While many CPS respondents reported that health problems or disabilities made them unable to work, the CPS data do not indicate how many were TennCare-eligible because of their disability status — a population that would likely be exempt from a work requirement.

- CPS questions are multiple choice, so additional details about enrollees’ circumstances and reasons for not working are not available.

Parting Words

All policy decisions have trade-offs. Medicaid work requirements may help low-income individuals find employment that leads to greater self-sufficiency. At the same time, work requirements may have unintended consequences if not thoughtfully designed. This brief — and follow-up reports on Tennessee’s experience with welfare-to-work and a summary of policy considerations — may help state policymakers weigh the trade-offs of a TennCare work requirement. Get the whole 3-part series here.

[i] Additional states have expanded Medicaid since 2014, but more recent data are unavailable.

Policy Arguments about Medicaid Work Requirements

Below are some examples of policy arguments you may have heard about Medicaid work requirements.

Social Contract: Many proponents of Medicaid work requirements argue that everyone who receives public assistance should work if they are able to work. Some opponents disagree, while others believe work requirements make sense for certain public assistance programs but not Medicaid. (15)

Incentives to Work: Some research has found that Medicaid creates a disincentive to work, while other studies have found a positive or neutral effect on labor market outcomes. Evidence suggests that most able-bodied adults on Medicaid are working, looking for work, in school, too sick to work, or caring for family members. (17) (18) Studies of Medicaid expansion have not found a negative impact on labor force participation, hours worked per week, or transitions from employment to non-employment. (21)

Path to Private Insurance: Since most employers provide health insurance benefits, Medicaid work requirements may help lift people out of poverty and transition to private plans. (19) On the other hand, low-wage workers are less likely to be offered or able to afford an employer-sponsored plan. (17) (20)

Health Status and Work: Research shows that work helps people improve their health. (16) At the same time, decreased access to care impedes people from improving their health so they are able to work. (16)

Purpose of Medicaid: Some argue work requirements would only apply to a small portion of Medicaid enrollees and would not be a significant change. (19) Others believe that work requirements would change Medicaid’s focus from providing health coverage to acting like a cash welfare program (i.e. TANF). (16)

Experience with TANF: Enforcing work requirements means people who do not comply lose their benefits. TANF work requirements have curbed enrollment as families either find work more quickly or are removed for not meeting work requirements. (14) Likewise, enforcing a Medicaid work requirement means those who do not comply could lose access to health care. (22)

*This brief was updated on Oct. 6, 2017 to link to information about TennCare eligibility.

References

Click to Open/Close

- Price, Thomas and Verma, Seema. Letter to Governors. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Online] 2017. https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/State-Innovation-Waivers/Downloads/March-13-2017-letter_508.pdf.

- U.S. Congress. H.R. 1628 – American Health Care Act of 2017. [Online] 2017. https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/hr1628/BILLS-115hr1628eh.pdf.

- —. Amendment to H.R. 1628 – Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017. [Online] 2017. https://www.budget.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/SENATEHEALTHCARE.pdf.

- Rosenbaum, Sara, et al. What Might a Medicaid Work Requirement Mean? The Commonwealth Fund. [Online] May 2017. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/blog/2017/may/medicaid-work-requirement.

- Dague, Laura, DeLeire, Thomas and Leininger, Lindsey. The Effect of Public Insurance Coverage for Childless Adults on Labor Supply. Working Paper 20111, National Bureau of Economic Research. [Online] May 2014. http://www.nber.org/papers/w20111.pdf.

- Garrett, Bowen, Kaestner, Robert and Gangopadhyaya, Anuj. Recent Evidence on the ACA and Employment: Has the ACA Been a Job Killer? 2016 Update. Urban Institute, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. [Online] February 2017. http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/88376/2001158-recent-evidence-on-the-aca-and-employment-has-the-aca-been-a-job-killer-2016-update_0.pdf.

- Garthwaithe, Craig, Gross, Tal and Notowidigdo, Matthew J. Public Health Insurance, Labor Supply, and Employment Lock. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. [Online] December 2013. http://www.columbia.edu/~tg2370/garthwaite-gross-notowidigdo.pdf.

- Baicker, Katherine, Finkelstein, Amy and Taubman, Sarah. The Impact of Medicaid on Labor Market Activity and Program Participation: Evidence from the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings. [Online] 2014 , 104(5). https://www.povertyactionlab.org/sites/default/files/publications/698%20medicaid%20and%20labor%20force%20participation%20AER%20May2014.pdf.

- Gooptu, Angshuman, et al. Medicaid Expansion Did Not Result in Significant Employment Changes or Job Reductions. Health Affairs 35(1). [Online] 2016. http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/35/1/111.full.pdf.

- Leung, Pauline and Mas, Alexandre. Employment Effects of the ACA Medicaid Expansions. NBER Working Paper 22540, National Bureau of Economic Research. [Online] July 2016. https://www.princeton.edu/~amas/papers/aca_060116.pdf.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Full-Benefit Medicaid Enrollees by Enrollment Group – FY 2014. [Online] http://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/distribution-of-full-benefit-medicaid-enrollees-by-enrollment-group/?dataView=1¤tTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D.

- Tennessee Division of Health Care Finance and Administration (TennCare). TennCare Enrollment Report for December 2016. [Online] https://www.tn.gov/assets/entities/tenncare/attachments/fte_201612.pdf.

- The Sycamore Institute. Analysis of March 2017 Current Population Survey data. [Online] https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps.html.

- Falk, Gene, McCarty, Maggie and Aussenberg, Randy Alison. Work Requirements, Time Limits, and Work Incentives in TANF, SNAP, and Housing Assistance. Congressional Research Service. [Online] February 2014. http://greenbook.waysandmeans.house.gov/sites/greenbook.waysandmeans.house.gov/files/R43400_gb.pdf.

- Rector, Robert. Work Requirements in Medicaid Won’t Work. Here’s a Serious Alternative. The Heritage Foundation. [Online] 2017. http://www.heritage.org/health-care-reform/commentary/work-requirements-medicaid-wont-work-heres-serious-alternative.

- Musumeci, MaryBeth. Medicaid and Work Requirements. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Online] March 2017. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-Medicaid-and-Work-Requirements.

- Ku, Leighton and Brantley, Erin. Myths About the Medicaid Expansion and the ‘Able-Bodied’. Health Affairs. [Online] March 2017. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2017/03/06/myths-about-the-medicaid-expansion-and-the-able-bodied/.

- —. Medicaid Work Requirements: Who’s at Risk. Health Affairs Blog. [Online] April 2017. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2017/04/12/medicaid-work-requirements-whos-at-risk/.

- Gitis, Ben and Hayes, Tara O’Neill. The Value of Introducing Work Requirements to Medicaid. American Action Forum. [Online] May 2017. https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/value-introducing-work-requirements-medicaid/.

- Garfield, Rachel, Rudowitz, Robin and Damico, Anthony. Understanding the Intersection of Medicaid and Work. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Online] February 2017. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-Understanding-the-Intersection-of-Medicaid-and-Work.

- Antonisse, Larisa, et al. The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Online] February 2017. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-The-Effects-of-Medicaid-Expansion-Under-the-ACA-Updated-Findings.

- Katch, Hannah. Medicaid Work Requirement Would Limit Health Care Access Without Significantly Boosting Employment. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. [Online] July 13, 2016. https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-work-requirement-would-limit-health-care-access-without-significantly.

Featured Image at top by Anthony Auston / CC BY-NC 2.0