No matter where you stand on the political spectrum, we all want Tennessee and Tennesseans to thrive. What are the roots of a thriving Tennessee, the factors that influence them, and the role of public policy? And why does that matter for Sycamore’s work?

Key Takeaways

- Families, businesses, and our economy all thrive when people enjoy good health, social and financial well-being, and the chance to make meaningful contributions to society.

- Both personal and environmental factors affect whether or not people and communities thrive.

- Public policies can influence both individual choices and the contexts in which we make those choices.

- Effective policy analysis requires us to understand the bigger picture — the complicated, overlapping, messy factors (both in and outside of policy) that shape our lives and communities.

The Roots of a Thriving Tennessee

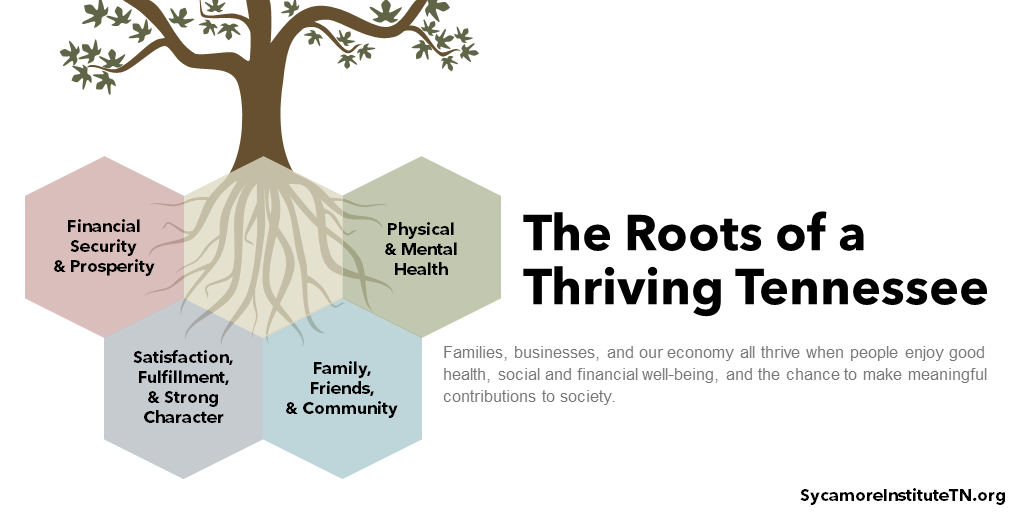

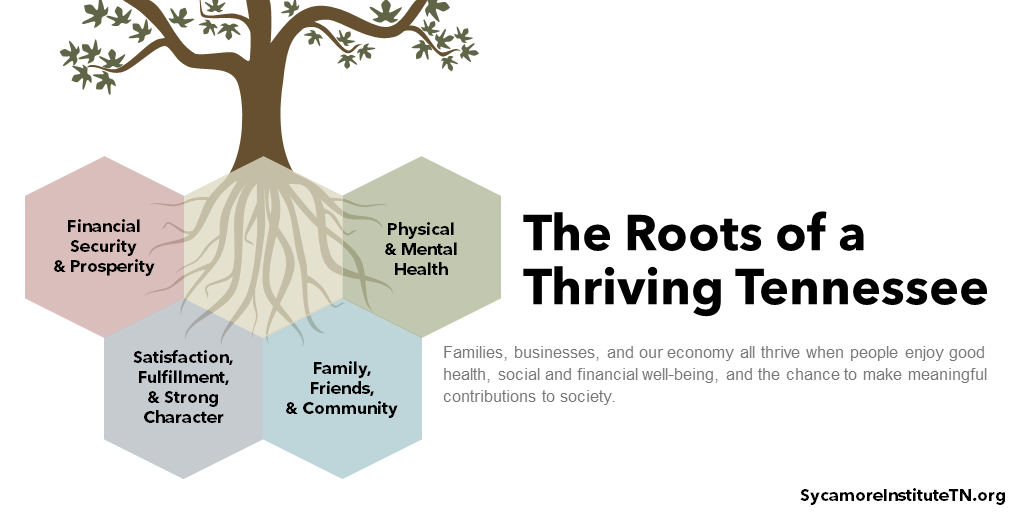

Families, businesses, and our economy all thrive when people enjoy good health, social and financial well-being, and the chance to make meaningful contributions to society. These are the roots of a thriving Tennessee. (Figure 1)

Research across multiple fields shows that a mix of elements contribute to human thriving and flourishing. (2) These elements include good physical and mental health, economic security and prosperity, and strong connections to family, friends, and community. (2) Our state also thrives when Tennesseans feel good about themselves and their lives. For example, are they happy and fulfilled? Do people feel like they serve a purpose, have a strong character, and make good choices? (2)

Figure 1

Factors that Influence These Roots

The roots of a thriving Tennessee are interconnected and mutually influential. The drivers of health, for example, tell us that health is influenced by not only clinical care but also education, income and wealth, and opportunities and choices for healthy living. At the same time, we know that physical health affects productivity and prosperity.

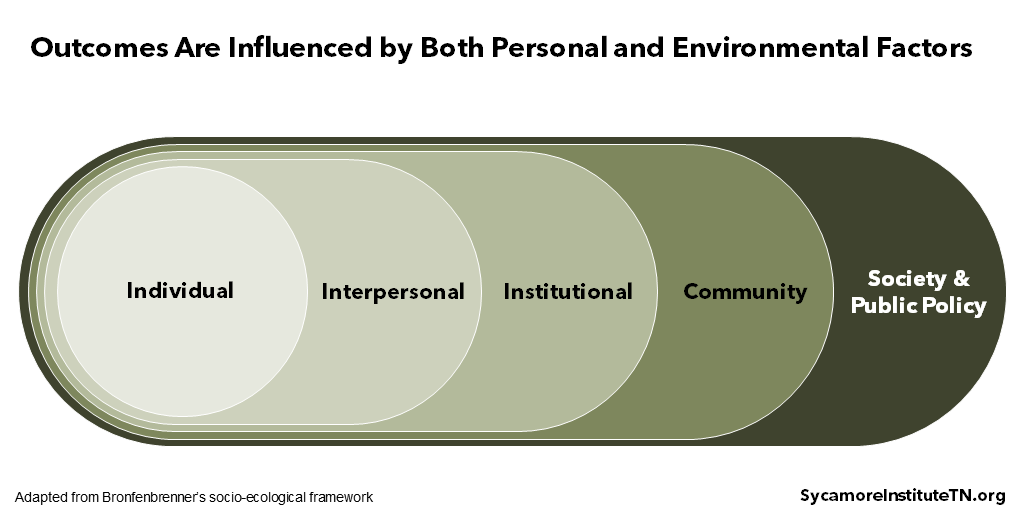

Both personal and environmental factors affect whether or not people and communities thrive. Figure 2 shows one way to think about how population outcomes are shaped by multiple, mutually influential systems. (3) At the core are people — our choices, beliefs, attitudes, biology, and personal experiences. Moving outward from the individual, we also see outcomes being shaped by our relationships, the places where we live, work, worship, and play, and the rules and norms of our society.

In practice, this means every aspect of society plays a role: family, religious and faith-based groups, the private sector, governments, nonprofits, and other civic clubs and organizations.

Figure 2

As an example, consider the host of factors that influence a behavior like smoking and smoking-related illnesses. (4)

- Individual: Some people may be more biologically prone than others to become addicted, and some may be more likely to experience adverse health outcomes from smoking.

- Interpersonal: Some people’s decisions about smoking may depend on if they have friends or family who smoke or the support of a family member in quitting. (5)

- Institutional: Workplaces or campuses may bar smoking in some areas. (6) People may also be nudged to quit smoking by a brief physician intervention or the availability of smoking cessation tools from employers or health plans. (7) (8)

- Community: Some communities may receive more advertising for tobacco products or have less access to smoking cessation services, which could influence decisions about smoking. (9) (5) (8)

- Society & Public Policy: State and local laws set the minimum smoking age, tobacco taxes, and where people can legally smoke. At the same time, smoking has become less socially accepted in the U.S. over time. (10) Both of these may be factors in whether and when people smoke.

The Ways Public Policy Influences Outcomes

Public policies can influence both individual choices and the contexts in which we make those choices. Public policy includes the actions (and inaction) of our federal, state, and local governments — including laws, regulations, guidance, and funding priorities. These tools affect almost every aspect of our lives — where we live, where we learn, where we work, and where we wander. And they can be applied in different ways to accomplish a desired outcome. Let’s again use smoking as an example to illustrate some of the different kinds of policy approaches.

Smoking is the leading cause of preventable death in the U.S. (11) In Tennessee, which has one of the highest smoking rates in the country, it claimed an estimated 11,000 lives in 2014. (12) If state policymakers wanted to reduce the number of smoking-related deaths, they could use different kinds of policy approaches to address that goal in very different ways (12):

- Community- or population-based approaches are broad and usually apply to everyone. An example would be a public awareness campaign on the dangers of smoking. This could keep some from beginning to smoke and lead others to quit smoking, which could reduce smoking-related deaths.

- Individual-level policy targets For example, the population-based public awareness campaign mentioned above may point people towards a tobacco quit-line. A quit-line is an example of an individual-level approach because it provides counseling and referrals to individuals who want to quit smoking.

- Upstream approaches try to prevent something negative before it happens, often by changing the context in which people make decisions. For example, minimum smoking ages, cigarette taxes, and public awareness campaigns are all upstream approaches, aimed in part at preventing smoking among youth.

- Midstream methods try to mitigate a negative outcome before it becomes too serious. For example, tobacco cessation services are aimed at helping current smokers quit, which can reduce their risk for smoking-related illness and death. (7)

- Downstream interventions treat a negative outcome. Getting people enrolled in health insurance coverage, for example, may help those with smoking-related illnesses get earlier treatment, better manage their health needs, and improve their quality of life.

Each approach has different implications for timeframe, cost, and evaluating results. For example, upstream methods of pursuing a goal are often less expensive than downstream methods. However, they can take longer to produce measurable results, and it is often much easier to evaluate the role of a midstream or downstream approach in achieving a certain outcome.

Political divisions often affect if and how public policy is used to influence outcomes. All policy actions come with trade-offs. Those trade-offs can involve grappling with different perspectives on the proper size and role of government or navigating conflicts between competing values and priorities. As a result, establishing and focusing on shared long-term goals sometimes takes a back seat to ideological objectives or short-term political priorities.

Why Does It Matter?

The connections between health, prosperity, and public policy are complicated, nuanced, and wide-ranging. Moving the needle toward a healthier and more prosperous Tennessee requires thoughtful analysis, taking the long view, and an appetite for breaking down silos. This is an iterative process that calls for stakeholders with diverse viewpoints to work together.

Effective policy analysis requires us to understand the bigger picture — the complicated, overlapping, messy factors (both in and outside of policy) that shape our lives and communities. Sycamore’s data-driven approach involves understanding goals, formulating good research questions, diagnosing areas for improvement, looking for solutions, and analyzing results to inform policies that support a thriving Tennessee. Doing this well means understanding both the role that policy plays in helping Tennesseans thrive and its relation to factors that influence our state’s success.

References

Click to Open/Close

- The Human Flourishing Program. Our Flourishing Measure. Harvard University’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science. https://hfh.fas.harvard.edu/measuring-flourishing.

- VanderWeele, Tyler J. On the Promotion of Human Flourishing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS). August 1, 2017. https://www.pnas.org/content/114/31/8148.

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. The Ecology of Human Development. Harvard University Press. 1917. Accessed via https://khoerulanwarbk.files.wordpress.com/2015/08/urie_bronfenbrenner_the_ecology_of_human_developbokos-z1.pdf.

- U.S. National Cancer Institute. A Socioecological Approach to Addressing Tobacco-Related Disparities. National Institutes of Health. 2017. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/monographs/22/docs/m22_complete.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Adolescent Health. Adolescents and Tobacco: Risk and Protective Factors. April 8, 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/adolescent-development/substance-use/drugs/tobacco/risk-and-protective-factors/index.html.

- American Cancer Society. Tobacco Use in the Workplace. July 19, 2018. https://www.cancer.org/healthy/stay-away-from-tobacco/smoke-free-communities/create-smoke-free-workplace/smoking-in-the-workplace-a-model-policy.html.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Quitting Smoking. December 11, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/cessation/quitting/index.htm.

- Rural Health Information Hub. Barriers to Establishing Tobacco Prevention and Control Programs in Rural Communities. 2019. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/tobacco/1/barriers.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tobacco Industry Marketing. May 4, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/tobacco_industry/marketing/index.htm.

- Cummings, K. Michael and Proctor, Robert N. The Changing Public Image of Smoking in the United States: 1964–2014. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. January 1, 2015. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3894634/#.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Health Effects of Cigarette Smoking. January 27, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/index.htm.

- —. Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs. 2014. ‘https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/best_practices/pdfs/2014/comprehensive.pdf.