Key Takeaways

- People with more income, wealth, education, and social standing tend to live longer, healthier lives.

- The relationship between health and these interconnected socioeconomic factors is complex and mutually influential.

- Differences in these factors can have compounding and cyclical effects that accumulate over generations.

Tennesseans’ prosperity and our health and well-being have a complex and mutually influential relationship. Each one affects the other. In our previous research we found that Tennessee’s high rates of chronic disease impose a significant cost on our economy. Focusing on another aspect of the relationship, this report explores how a person’s income, wealth, and other socioeconomic factors can influence their health.

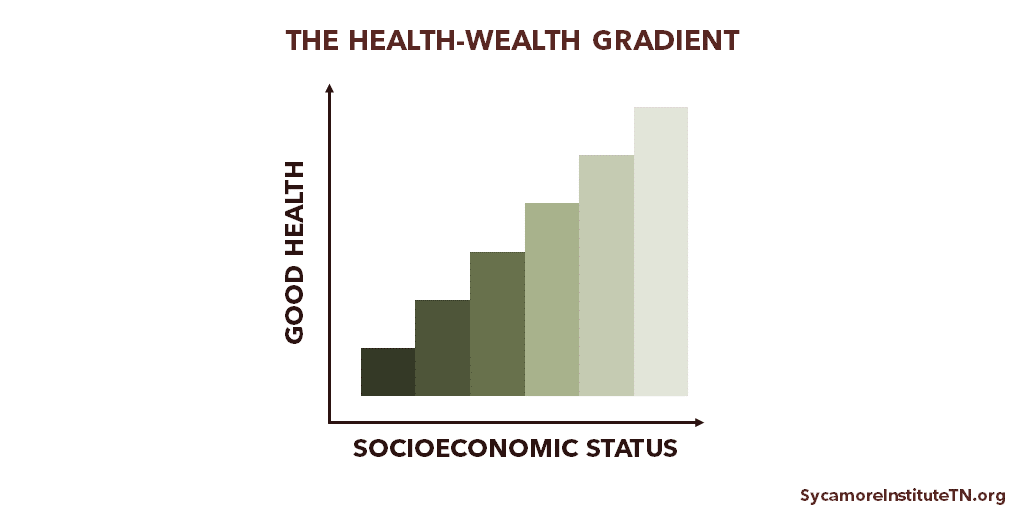

The Health-Wealth Gradient

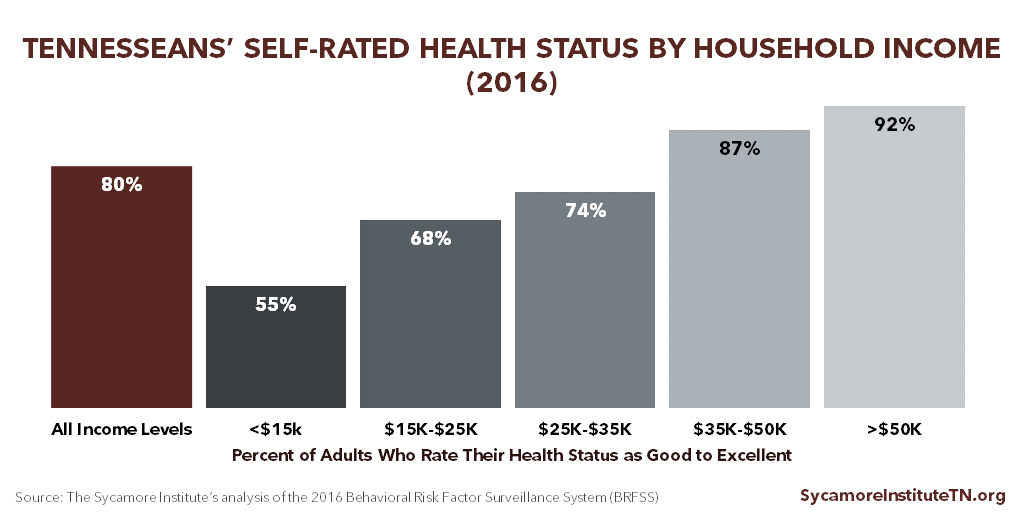

People with more income, wealth, education, and social standing tend to live longer, healthier lives. (1) As incomes rise, Tennesseans are increasingly likely to rate their health as good-to-excellent (Figure 1). Academics call this relationship between health and socioeconomic status broadly the “health-wealth gradient” (Figure 2) — although “wealth” is just one component of socioeconomic status (see below). (2)

Figure 1

Figure 2

Defining Measures of Socioeconomic Status

There are many social and economic factors that affect people’s lives. (4) These individual metrics are related but not interchangeable. The most commonly used are income, wealth, and education.

Income and Wealth

Income generally includes resources received on a regular basis for work or through investments, while wealth is economic assets that have been accumulated over time. Sources of income include work, public assistance, retirement and pension plans, and interest or dividends from savings and investments. Wealth includes things like homes, land, vehicles, savings, financial investments, and businesses. Additionally, wealth is more likely to be passed down through generations. An estimated 25 to 45% of wealth is inherited, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research. (5)

The Relationship Between Income, Wealth, and Education

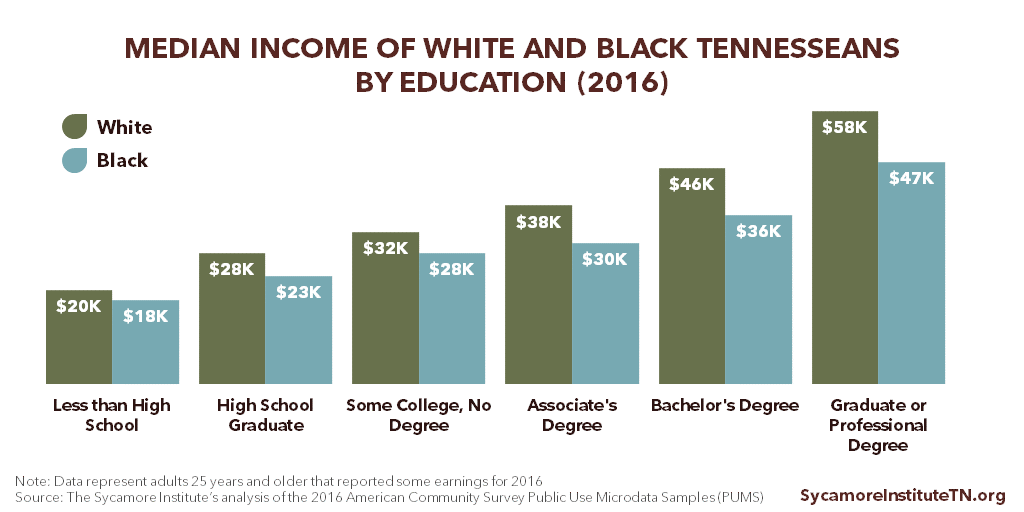

People with more education tend to have higher incomes. Among those with similar levels of education, however, income often varies by age, race/ethnicity, and sex. (6) For example, white and black Tennesseans with the same education levels have different median incomes. (Figure 3)

Meanwhile, people with similar incomes and/or education may have very different levels of wealth. (6) For example, in 2016, the median net worth of U.S. households with a white college graduate was $397,100 compared to $100,000 among U.S. households with a black or Hispanic college graduate. (7)

Figure 3

Measuring Socioeconomic Status

Measures of socioeconomic status that include wealth in addition to income and education provide a more complete picture of economic resources available both now and in the future. (8) (9) Wealth often helps people financially weather adverse life events (e.g. illness, unemployment, labor market changes), reduces stress, and provides access to other resources. (6) At the same time, barriers to obtaining wealth and resources (such as debts that prevent a person from qualifying for a job or buying homes/vehicles) can have a negative effect on health.

Unfortunately, comprehensive data on wealth are not routinely collected. Income is the more common metric in health research and is typically measured at a single point in time. Many people are unwilling to report information about their personal wealth, and it can be difficult to calculate. These limitations makes it challenging to thoroughly explore the relationship between health and wealth.

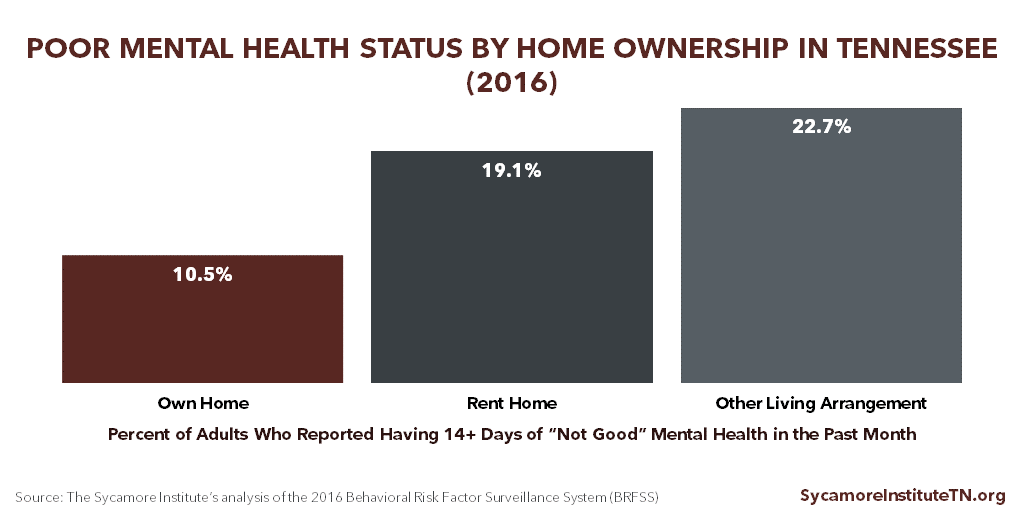

Some researchers use a single measurement as a proxy for wealth to explore the relationship between health and wealth (i.e. home value, home ownership, liquid assets). (6) For example, in 2016, there were notable differences in the self-reported mental health status of Tennessee adults who owned their homes and those who did not. (Figure 4) Among homeowners, 10.5% reported having 14+ days of “not good” mental health in the past month — compared with 19.1% of renters and 22.7% of those with “other living arrangements.”

Figure 4

Health and Socioeconomic Status: A Complex Relationship

The relationship between health and interconnected socioeconomic factors is complex and mutually influential. (11)

Opportunities for Better Health

Socioeconomic status can affect opportunities for individuals to improve their health. Greater income and wealth generally provide better access to medical care, nutritious food, safe neighborhoods and communities, opportunities for physical activity, and high quality education. (8) As an example, Tennessee counties with higher median incomes tend to have more practicing primary care physicians per resident. (Figure 5)

These types of opportunities and resources can also influence individual behaviors like diet, exercise, smoking, and use of preventive care. For instance, the lower a Tennessean’s household income, the more likely they are to smoke. (Figure 6)

Figure 5

Figure 6

The Role of Work

Work also has a complex relationship with health and socioeconomic status. As an example, healthier individuals are more productive workers and miss fewer days of work for health reasons. (14) Research has also found that inconsistent work and the fear of job loss is associated with poorer physical and mental health. (15) (16)

Work can create opportunities for better health, but the nature of the work matters. (8) Work status influences many different drivers of health, including income, environmental exposures, and access to health insurance. For instance, people with lower status jobs report higher levels of stress, less control over working conditions, increased exposure to hazardous chemicals at work, fewer financial and personal support resources, and are more likely to have to work when they are sick. Meanwhile, higher status workers are more likely to have higher incomes, benefits (e.g. paid sick leave, health insurance), and more control over their work (e.g. flexible work schedules, telecommuting options). (17) (18)

The Impact of Chronic Stress

Chronic, severe stress (aka toxic stress) from early trauma and adversity can disrupt childhood brain development. Decades of science shows that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as exposure at a young age to household dysfunction or psychological, physical, or sexual abuse, can cause stress that is toxic to the developing brain. Based on additional research, other childhood adversities like community violence, poverty, and neighborhood distress are also believed to trigger the same toxic stress. (19) (20)

Research has found a clear link between childhood toxic stress and long-term negative outcomes for health and socioeconomic status. Health effects include higher risks of disease, negative health behaviors (e.g. smoking and substance abuse), and premature death. (11). The socioeconomic effects, which can influence a person’s health, are also varied. For example, people who faced ACEs during childhood and adolescence are less likely to do well in school or attain higher levels of education. (21) They are more likely to live in poverty as adults and report serious job-related and financial problems and frequent absences from work. (21) (22)

Exposure to chronic stressors in adulthood is also associated with poorer health outcomes — and is more likely for adults with lower socioeconomic status. Adults with limited economic resources are more likely to face (and have fewer resources to cope with) housing problems, food insecurity, crime and violence, and financial hardship. According to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, these circumstances can trigger chronic, sustained stress that creates “wear and tear on bodily systems” that are damaging to health. (23) The health outcomes of these challenges during adulthood mirror those of ACEs — negative health behaviors, increased risk of disease, and premature death. (11) (23)

Cyclical and Intergenerational Effects

Differences in socioeconomic factors can have compounding and cyclical effects that accumulate over generations. The opportunities for economic mobility and better health that an individual has today also influences those they will have later in life. For example, residents of lower-income neighborhoods tend to have fewer opportunities for good health and quality education. Lack of a quality education can in turn reduce a person’s access to opportunities and resources to improve their health and education, as well as that of their children. (8)

Related Work by The Sycamore Institute

The Roots of a Thriving Tennessee

How Education Influences Health in Tennessee

How Early Childhood Experiences Affect Lifelong Health

The Economic Impact of Chronic Disease in Tennessee

Healthy Debate 2018: Connections between Tennessee’s Budget, Economy, and Health and Well-Being

References

Click to Open/Close

- Semyonov, Moshe, Lewin-Epstein, Noah and Masikileyson, Dina. Where Wealth Matters More for Health: The Wealth-Health Gradient in 16 Countries. Social Science & Medicine, 81: 10-17. [Online] 2013. [Accessed on January 8, 2018.] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23422055.

- Deaton, Angus. Policy Implications of the Gradient of Health and Wealth. Health Affairs, 21(2): 13-30. [Online] March/April 2002. [Accessed on December 20, 2017.] https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.13.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). [Online] 2017. [Accessed on September 12, 2017.] Accessed via https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_2016.html.

- Evans, William, Wolfe, Barbara and Adler, Nancy. Chapter 1: The SES and Health Gradient: A Brief Review of the Literature. The Biological Consequences of Socioeconomic Inequalities, pgs 1-37. [Online] November 9, 2012. [Accessed on January 8, 2018.] https://www.russellsage.org/sites/all/files/wolfe%20intro.pdf.

- Kopczuk, Wojciech and Lupton, Joseph p. To Leave or Not to Leave: The Distribution of Bequest Motives. NBER Working Paper 11767, National Bureau of Economic Research. [Online] November 2005. [Accessed on March 20, 2018.] http://www.nber.org/papers/w11767.pdf.

- Braveman, Paula A, et al. Socioeconomic Status in Health Research: One Size Does Not Fit All. JAMA, 294(22): 2879-2888. [Online] 2005. [Accessed on January 9, 2018.] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/202015?redirect=true.

- Detting, Lisa J, et al. “Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. FEDS Notes, Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. [Online] September 27, 2017. [Accssed on March 20, 2018.] https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2083.

- Braveman, Paula, Egerter, Susan and Barclay, Colleen. Income, Wealth and Health. Issue Brief #4, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. [Online] April 2011. [Accessed on January 9, 2018.] http://www.lchc.org/wp-content/uploads/02_LCHC_EconJustice.pdf.

- Bricker, Jesse, et al. Measuring Income and Wealth at the Top Using Administrative and Survey Data. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1: 261-331 The Brookings Institution. [Online] 2016. [Accessed on March 20, 2018.] https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/brickertextspring16bpea.pdf.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2016 American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Samples (PUMS). [Online] 2017. [Accessed on January 16, 2018.] Accessed via https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data/pums.html.

- Adler, Nancy and Stewart, Judith. Health Disparities across the Lifespan: Meaning, Methods, and Mechanisms. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1186(2010): 5-23. [Online] February 16, 2010. [Accessed on January 8, 2018.] http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05337.x/epdf.

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2017 County Health Rankings. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. [Online] 2017. http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2012-2016 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. [Online] 2017. [Accessed on December 7, 2017.] Accessed via factfinder.census.gov.

- Bloom, David E and Canning, David. The Health and Wealth of Nations. Science, 287: 1208-1209. [Online] 2000. http://kie.vse.cz/wp-content/uploads/Bloom-Canning-2000.pdf.

- Quinlan, Michael and Bohle, Philip. Overstretched and Unreciprocated Committment: Reviewing Research on the Occupational Health and Safety Effecys of Downsizing and Job Insecurity. International Journal of Health Services, 39(1): 1-44. [Online] 2009. [Accessed on April 10, 2018.] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19326777.

- Sverke, Magnus, Hellgren, Johnny and Naswall, Katharina. No Security: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Job Insecurity and Its Consequences. Journal of Occupational Health and Psychology, 7(3): 242-264. [Online] 2002. [Accessed on April 10, 2018.] https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2a5f/ea74ecc95113adf0385104adcb18a8c0333c.pdf.

- Clougherty, Jane E, Souza, Kerry and Cullen, Mark R. Work and its role in shaping the social gradient in health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1186(2010), 102-124. [Online] February 2010. [Accessed on January 10, 2018.] http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05338.x/full.

- Kossek, Ellen Ernst and Lautsch, Brenda A. Work-Life Flexibility for Whom? Occupational Status and Work-Life Inequality in Upper, Middle, and Lower Level Jobs. Academy of Management Annals. [Online] 2017. [Accessed on April 10, 2018.] https://journals.aom.org/doi/10.5465/annals.2016.0059.

- Wadsworth, Martha E and Rienks, Shauna L. Stress as a Mechanism of Poverty’s Ill Effects on Children: Making a Case for Family Strengthening Interventions that Counteract Poverty-Related Stress. American Psychological Association. [Online] July 2012. http://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/newsletter/2012/07/stress-mechanism.aspx.

- Bruner, Charles. ACE, Place, Race, and Poverty: Building Hope for Children. Academic Pediatrics (17): S123-S129. [Online] September-October 2017. https://www.academicpedsjnl.net/article/S1876-2859(17)30352-2/pdf.

- Metzler, Marilyn, et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Life Opportunities: Shifting the Narrative. Children and Youth Services, 72: 141-149. [Online] January 2017. [Accessed on December 14, 2017.] http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740916303449.

- Anda, Robert F, et al. Childhood Abuse, Household Dysfunction, and Indicators of Impaired Adult Worker Performance. The Permanente Journal 8(1): 30-38. [Online] Winter 2004. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4690705/.

- Egerter, Susan, Braveman, Paula and Barclay, Colleen. Stress and Health. Issue Brief #3, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. [Online] March 2011. [Accessed on January 10, 2018.] https://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2011/rwjf70441.

- Kawachi, Ichiro, Adler, Nancy E and Dow, William H. Money, Schooling, and Health: Mechanisms and Causal Evidence. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1186(2010): 56-68. [Online] 2010. [Accessed on January 10, 2018.] http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05340.x/epdf.