The health status of the average Tennessean is worse than the average American. To improve our state’s health outcomes, policymakers should understand the complex set of factors that influence them. This section of Healthy Debate 2018 summarizes the state of health in Tennessee and several unique challenges facing rural areas of the state. It also introduces the Tennessee Health & Well-Being Index, a tool created by The Sycamore Institute to track the drivers of population health in Tennessee.

The State of Health in Tennessee

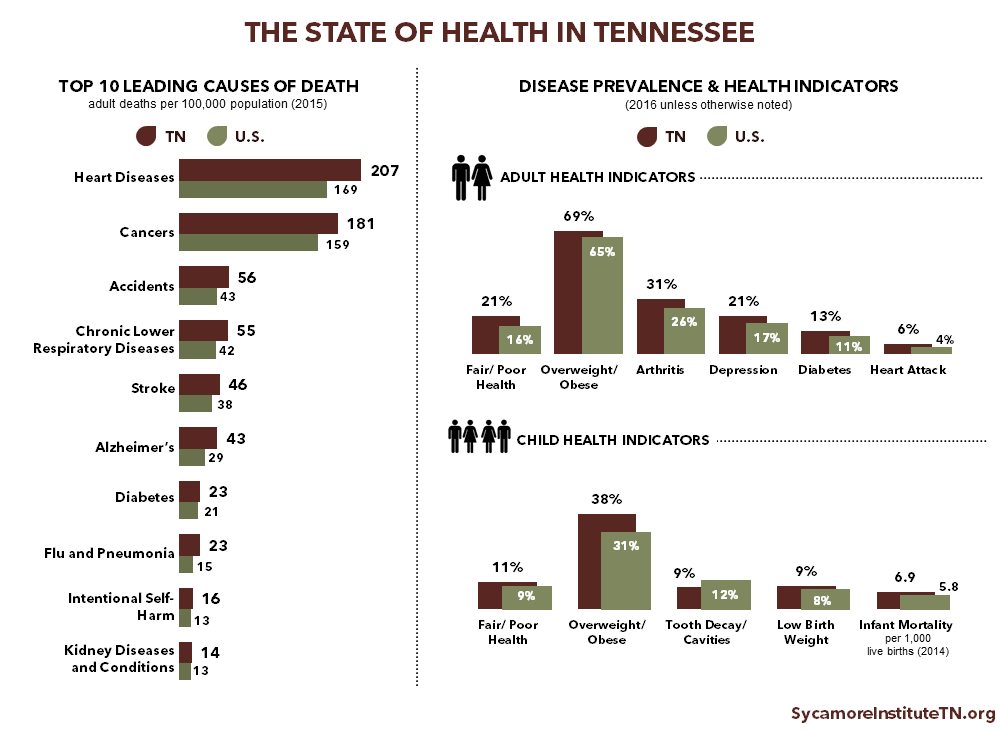

Tennessee trails the rest of the nation in many key health indicators and outcomes. Adults rate both their own and their children’s overall health status worse in Tennessee than nationally. Additionally, Tennessee has higher rates than most other states of infant mortality and chronic conditions like diabetes, depression, cardiovascular disease, and adult and childhood obesity.

Seven of the top 10 leading causes of death in Tennessee can be attributed to chronic health conditions. The leading causes of death in Tennessee largely mirror the nation’s leading causes. However, for each of the top 10 causes of death, Tennessee’s mortality rates are higher than the national rates.

Tennessee typically ranks in the bottom 10 states on national health rankings because of these differences in both death and disease rates. (1)

Health disparities are prevalent in Tennessee. Population-based averages often hide differences in health between particular groups. Racial and ethnic minorities, individuals with lower levels of education and income, and individuals living in rural areas experience poorer health outcomes largely due to differences in the drivers of health.

Source: See citation (2) in References and Notes

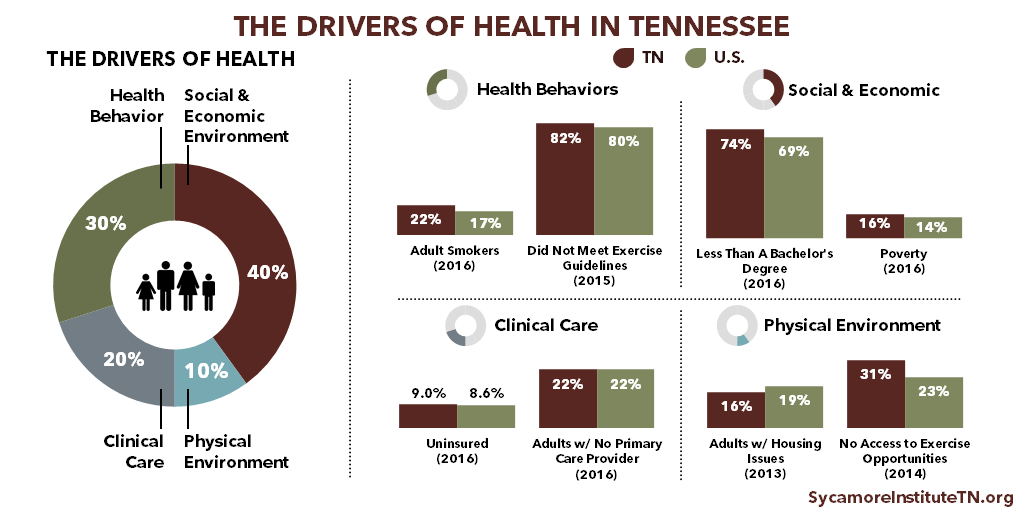

The Drivers of Health

Health means more than just health care. While access to clinical care is a contributing factor, health behaviors and our social and economic environments are the leading drivers of health outcomes. For example, poor nutrition, lack of physical activity, and tobacco use all increase one’s risk of developing a chronic condition. Risk also increases as income and education decline. These factors interconnect in complex ways. For instance, our environments can encourage or discourage certain health behaviors.

Many key factors that contribute to poor health are more prevalent in Tennessee than nationally. Tennessee has higher rates of smoking and poverty and lower rates of exercise and insurance coverage than the U.S. as a whole. In fact, nearly 1 in 4 adult Tennesseans smoke cigarettes, a higher rate than all but 7 states. (4) Smoking is the most preventable cause of premature death in the country, and it is associated with heightened risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. (5)

Source: See citation (3) in References and Notes

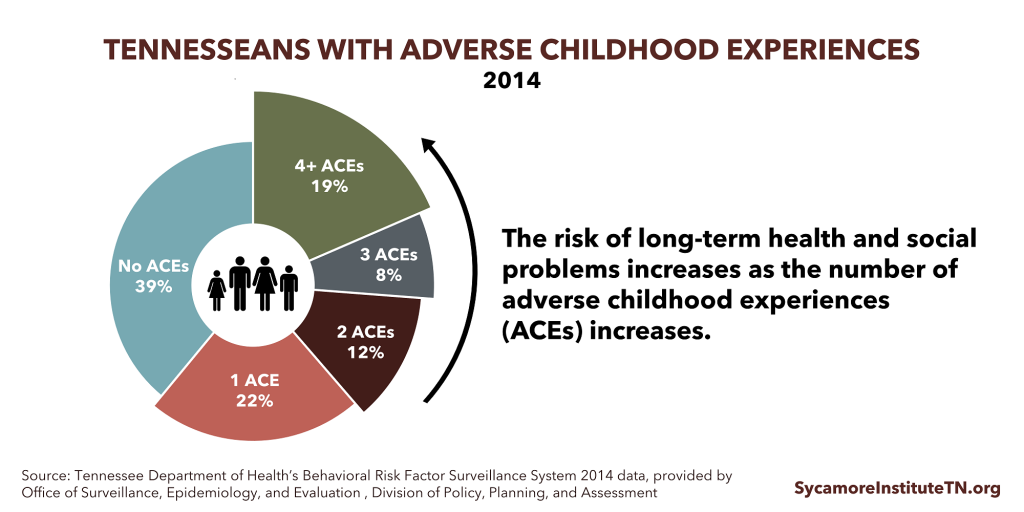

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are among the best examples of the complex set of factors that influence health. Childhood and adolescence are critical times for human brain development. Science has found a clear link between experiences at this age that cause chronic and severe stress — such as exposure to household dysfunction or psychological, physical, or sexual abuse — and health and well-being later in life. As exposure to ACE-related toxic stress increases, so does the risk of a wide variety of outcomes with long-term negative effects, such as alcohol abuse, drug abuse, smoking, and heart disease.

Increasing children’s resilience to toxic stress can reduce or overcome the effects of ACEs. Successful approaches to ACEs recognize that a wide variety of influencers (e.g. the health care system, education, child welfare, and criminal justice) can play a role in supporting children, parents, and families. Identifying and addressing sources of childhood toxic stress can have a lasting, multigenerational impact on Tennesseans’ health, productivity, and prosperity.

Source: See citation (6) in References and Notes

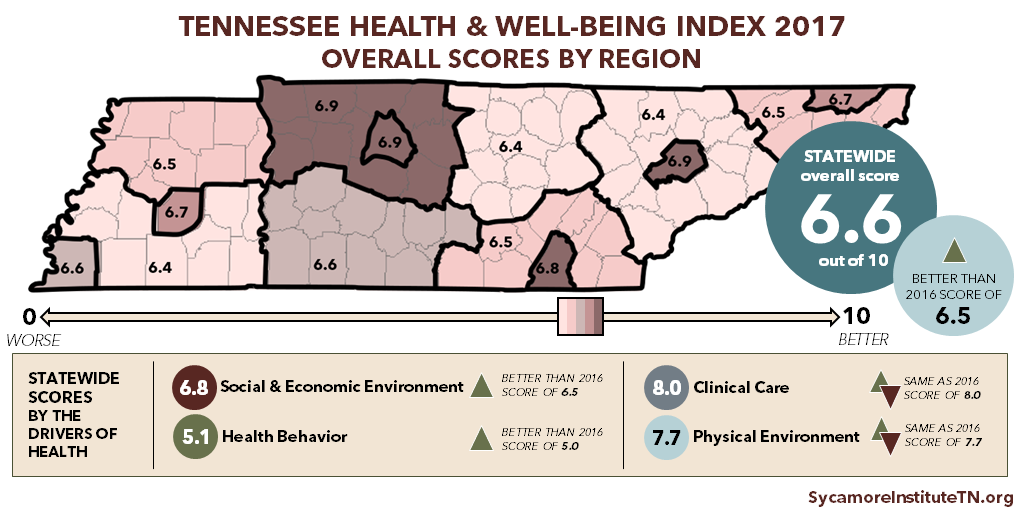

The Tennessee Health & Well-Being Index

The Sycamore Institute’s Tennessee Health & Well-Being Index is a tool for measuring the drivers of population health in our state and tracking them over time. Using the most recent data available, the Index measures factors that influence health at the state and regional level. It also highlights health outcomes and areas of relative strength and opportunities for improvement in the drivers of health.

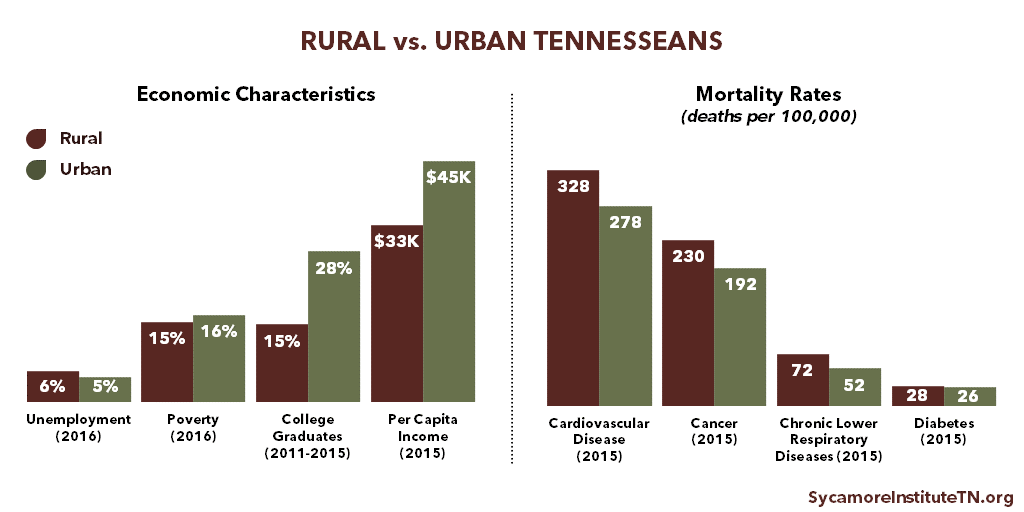

Tennessee’s Rural Health Challenges

Tennessee’s rural areas face unique demographic, economic, health, and health system challenges. About 1.5 million Tennesseans (or 22%) live in a rural area. (8) Tennesseans living in rural areas tend to be older, sicker, and have lower incomes on average than those in other areas. (9)

Source: See citation (7) in References and Notes

Compared to urban areas, Tennesseans living in rural areas:

- Are older.

- Have lower per capita incomes.

- Are more likely to be unemployed.

- Have less education.

- Suffer from higher rates of diabetes, obesity, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, prescription drug overdoses, and premature death.

Residents of rural areas often have less access to health care due to provider shortages, hospital closures, and increased travel distances to providers. Since 2010, 8 rural hospitals in Tennessee have closed, resulting in a loss of 326 inpatient care beds. (10) As of 2015, almost 1 in 4 Tennessee hospitals was at increased risk of closure. (11) Hospital closures leave many people without a local source of care, particularly for emergencies. In 2015, Tennessee’s rural hospitals provided more than $292 million in uncompensated care. (12) Hospitals also provide employment and produce economic growth for the communities they serve.

Related Work by The Sycamore Institute

Tennessee Health & Well-Being Index

March 2017

How Childhood Experiences Affect Lifelong Health

July 2017

References

Click to Open/Close

- America’s Health Rankings for 2016 (TN Ranking: 44th), 2015 (TN Ranking: 43rd), and 2014 (TN Ranking: 45th) (https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/2016-annual-report/state/TN)

- The Sycamore Institute’s analysis of:

- 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System – all adult health indicators (accessed on October 26, 2017 via https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/)

- CDC WONDER – 10 leading causes of death (2015) (accessed on October 26, 2017 via https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html)

- CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics – infant mortality (2014) (accessed on October 27, 2017 via https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/infant_mortality.htm)

- CDC’s National Vital Statistics System – low birthweight infants (2016 – preliminary) (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/report002.pdf)

- Tennessee Department of Health – low birthweight (2016) (https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/health/documents/TN_Births_Low_Birth_Weight_-_2016.pdf)

- 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health – all other child health indicators (accessed on October 26, 2017 via www.childhealthdata.org)

- The Drivers of Health exclude the role of genetics and are based on analysis by Hyojun Park et al (http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/sites/default/files/Park_AmJPrevMed_2015.pdf) and Harry Heiman et al (http://kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/). Data are based on The Sycamore Institute’s analysis of:

- 2016 American Community Survey – educational attainment, poverty, insurance coverage rates (accessed in September 2017 via https://factfinder.census.gov/)

- 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System – health behaviors, primary care provider (accessed on October 27, 2017 via https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/)

- 2017 County Health Rankings – housing issues, access to exercise opportunities (accessed via http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/tennessee/2017/overview)

- The Sycamore Institute’s analysis of the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (accessed on October 27, 2017 via https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/)

- The U.S. Surgeon General’s “The Health Consequences of Smoking 50 Years of Progress” (2014) (https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/50th-anniversary/index.htm)

- The Sycamore Institute’s analysis of 2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System – adult ACEs prevalence (obtained from the Tennessee Department of Health’s Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Evaluation)

- The Sycamore Institute’s analysis of:

- S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service state data for Tennessee – unemployment, education, income (accessed on October 27, 2017 via https://data.ers.usda.gov/reports.aspx?StateFIPS=47&StateName=Tennessee&ID=17854)

- 2016 American Community Survey– poverty (accessed in September 2017 via https://factfinder.census.gov/)

- Tennessee Department of Health Death Certificate Data – 2015 mortality rates (https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/health/documents/TN_Deaths_-_2015.pdf)

- U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service state data for Tennessee (accessed on October 27, 2017 via https://data.ers.usda.gov/reports.aspx?StateFIPS=47&StateName=Tennessee&ID=17854)

- U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service state data for Tennessee (accessed on October 27, 2017 via https://data.ers.usda.gov/reports.aspx?StateFIPS=47&StateName=Tennessee&ID=17854)

- University of North Carolina’s database of rural hospital closures since January 2010 (accessed on September 4, 2017 via http://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures/). Differs from a June 22, 2017 TSI report that cited 9 closures and 354 beds, which was based on the same data source as accessed on May 22, 2017. At that time, the UNC database did not yet reflect the reopening of Scott County Community Hospital in Oneida, TN.

- The North Carolina Rural Health Research Program’s Geographic Variation in Risk of Financial Distress Among Rural Hospitals (page 1) (January 2016) (accessed via http://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/product/geographic-variation-in-risk-of-financial-distress-among-rural-hospitals/)

- The Tennessee Hospital Association’s 2017 Rural Impact Report (page 2) (https://secure.tha.com/files/pr/Rural%20Impact%20Report%202017%20Final.pdf)