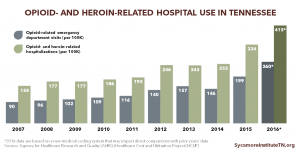

Tennessee has made progress in reducing the supply of prescription opioids by targeting efforts to improve provider prescribing practices and reducing the number of pill mills. However, the epidemic is evolving with individuals appearing to switch from prescription opioids to illicit and stronger opioids like heroin and fentanyl. At the same time, opioid overdoses and the number of babies born with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) continue to rise. The nature of addiction explains many of these trends and the continued demand for opioids in Tennessee. (1)

This report takes a comprehensive look at various elements of addressing addiction from prevention to recovery. This is the second in a 3-part series that sets the stage for ongoing analyses of Tennessee’s opioid epidemic.

Key Takeaways

- Addiction is a chronic, relapsing brain disease that requires long-term care and management.

- Reducing demand for opioids involves a spectrum of behavioral health interventions to promote health and well-being, prevent misuse, and treat addiction.

- Effective treatment and recovery programs include early intervention, detox, counseling, medications, and recovery support services.

- Financial obstacles, treatment capacity, social stigma, and personal hurdles can all create barriers to treatment.

Bottom Line

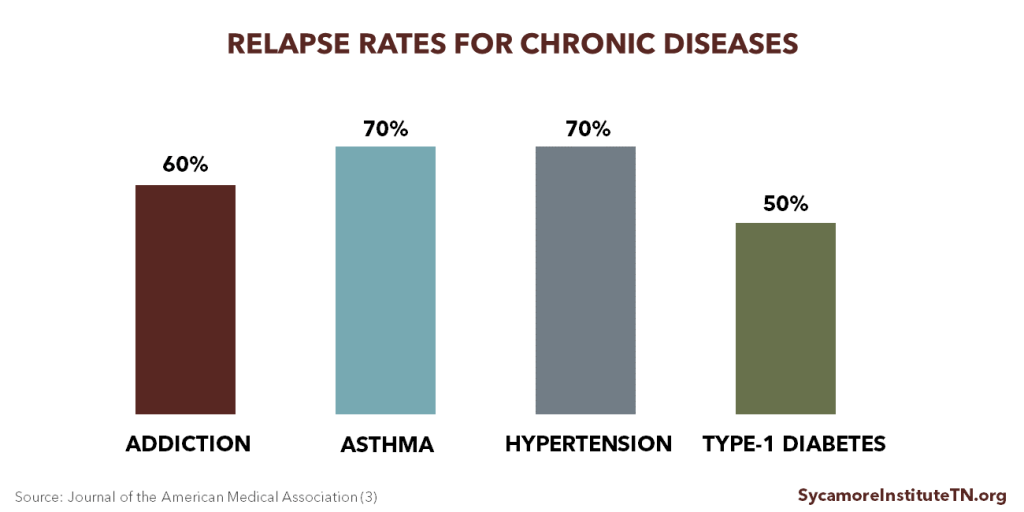

Addiction, also known as substance use disorder (SUD), is a chronic, relapsing brain disease. It shares many characteristics with other chronic diseases, including requiring long-term care and management.

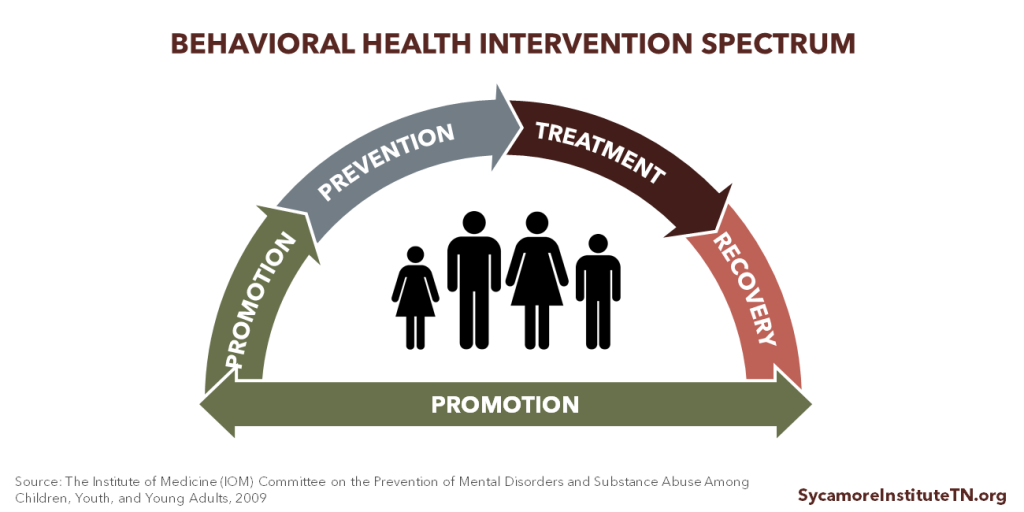

Reducing demand for opioids involves a variety of behavioral health interventions aimed at broadly promoting health and well-being, preventing opioid misuse, and treating opioid addiction.

- Activities that promote health and well-being are typically upstream, “big picture” efforts that address the drivers of health and the risk factors for addiction. They play a role in prevention but also support the entire spectrum of behavioral health interventions.

- Prevention efforts target specific risk factors and protective factors associated with drug addiction and abuse. They can target broad communities and schools or specific high-risk groups and individuals.

- Effective treatment and recovery programs include early intervention, medically-assisted detoxification, counseling, medications, and recovery support services and are tailored to individual needs.

Financial obstacles, treatment capacity, and social stigma can all create barriers to accessing treatment. Private health insurance, Medicaid, and public safety net coverage can reduce financial obstacles, but social stigma around addiction and certain treatments may reduce access. Coverage practices, restrictions, and payments all influence treatment capacity.

Understanding Addiction

Addiction or substance use disorder (SUD) is a chronic, relapsing brain disease that shares many of the same characteristics of other chronic diseases like asthma, high blood pressure, and diabetes. (2) SUD is characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use, despite harmful consequences.

As with all health outcomes, the drivers of health (physical, social, and economic environments and health behaviors) play a role in SUD. Additionally, some individuals are more likely to become addicted to a substance because of their genetic makeup. (3)

Table 1. Factors that Increase or Protect Against Risk of Drug Abuse |

|

|---|---|

| Risk Factors | Protective Factors |

| Adverse childhood experiences | Good self-control |

| Genetic predisposition | Parental monitoring and support |

| Aggressive behavior in childhood | Positive relationships |

| Community poverty | Academic competence |

| Poor social skills | School anti-drug policies |

| Availability of drugs at school | Neighborhood pride |

Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse and SAMHSA (4)

Figure 1

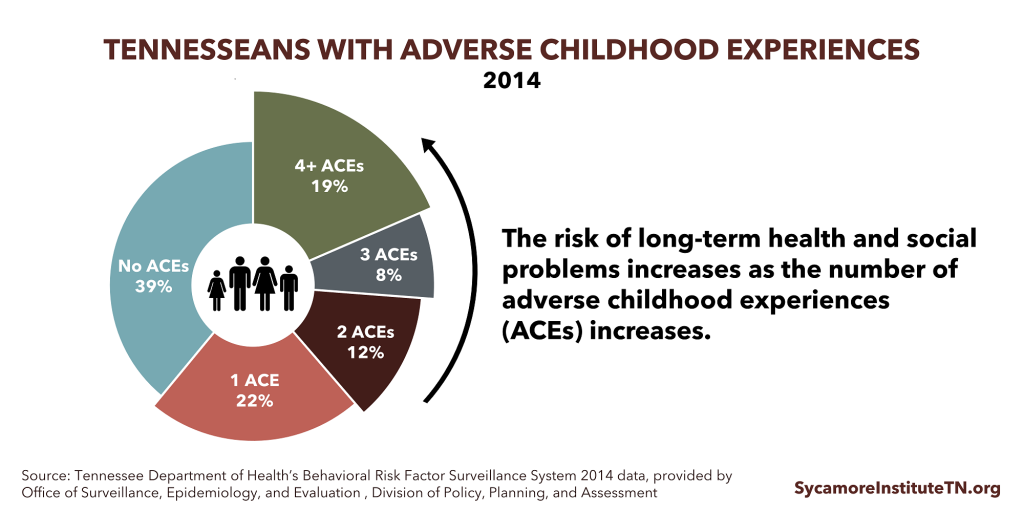

Risk factors and protective factors both influence an individuals’ lifelong risk for substance use (Table 1). For example, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and childhood toxic stress are associated with an increased risk of substance abuse. In 2014, 61% of adult Tennesseans had experienced at least one ACE, and 18.5% had experienced 4 or more ACEs. As the number of ACEs increases, so does the risk of long-term health and social problems, including addiction (Figure 1). Protective factors can counterbalance the effects of these risk factors. For example, programs and services that support a child’s social and emotional development, encourage positive relationships, and provide parenting support help build a strong foundation for long-term health and well-being.

Like other chronic diseases, treating SUD requires long-term care and management. Addiction changes brain functions and chemistry in ways that make it increasingly difficult for a person to control their substance use. This can lead to cycles of relapse and recovery. Addiction, however, is a treatable disease and can be successfully managed like other chronic diseases. In fact, treatment non-compliance and relapse rates are similar to other chronic diseases (Figure 2). (3)

Figure 2

A Comprehensive Approach to Reducing Opioid Demand

Science has revealed a variety of ways to address behavioral health issues like substance use disorders and mental illnesses. Reducing demand for opioids involves a comprehensive spectrum of interventions, which includes (Figure 3):

- PROMOTION of health and well-being through supportive environments and strong relationships,

- PREVENTION of substance use disorders,

- TREATMENT of individuals diagnosed with a substance use disorder, and

- RECOVERY services to help individuals as they recover from a substance use disorder. (5) (6)

Figure 3

Promoting Health & Well-Being

Activities that promote health and well-being are typically upstream, “big picture” efforts that address the drivers of health and the risk factors for addiction. These efforts help build resilience — a protective factor against addiction — during early childhood and adolescence, critical times for human brain development.

The promotion of health and well-being also supports the entire spectrum of behavioral health interventions. For example, these efforts can increase opportunities for safe and stable housing, quality education or training, and employment. Supportive services that help individuals with housing, education, and employment are also a key component of treatment and recovery. (7) (8)

Prevention of Substance Abuse

Prevention activities target the risk factors and protective factors associated with drug addiction and abuse. Examples include public education campaigns, evidence-based prevention programs, and education for health care providers. (9)

Adolescence is not only an important time for brain development, but most people who abuse drugs start when they are teenagers. These factors make adolescence an ideal time for preventing drug addiction. Evidence-based prevention programs for children and adolescents often:

- Target all forms of drug use,

- Are sensitive to the needs of individuals, families, and communities,

- Include skills-based training to help individuals resist drugs, strengthen personal commitments and reinforce attitudes against drug use, and increase social competency,

- Use interactive methods, and

- Occur at the individual, family, school, and community levels. (10)

Every $1 spent on school-based prevention yields an estimated return of up to $18 in reduced educational, health care, and lost productivity costs and improved quality of life, according to the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). SAMHSA estimated that, if effective school-based prevention programs were implemented nationwide, youth (ages 12-15) rates of marijuana use would decline by 12% and cocaine use by 46%. (11)

Efforts to reduce the supply of prescription opioids are an important part of preventing opioid abuse and addiction. Getting overlapping prescriptions from multiple providers and taking high dosages are both risk factors for opioid abuse and overdose. (12) Reducing prescription opioid abuse also helps prevent people from starting to use heroin.

Data can serve as a tool to guide and refine prevention efforts. If public health and law enforcement officials have access to the same real-time data sources, they can identify geographical hot spots to target and tailor prevention activities. (13)

Treatment and Recovery

Evidence-based addiction treatment and recovery calls for early intervention, detoxification, counseling, medication, and recovery support services. The specific combinations and durations of these components should be tailored to meet the needs of each individual. Participating in treatment for less than 90 days, however, has limited effect, according to NIDA. (14) (7) Individuals may also need to go through treatment several times to recover. (15)

Every $1 spent on evidence-based treatment yields an estimated return of up to $12 in reduced health care and criminal justice costs, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). NIDA has found that treatment reduces drug use and crime by 40-60% while increasing employment prospects by 40%. (7) (10)

Elements of an effective program include:

EARLY INTERVENTION: Before individuals can undergo treatment, their addiction or misuse must first be identified. Many people end up in treatment only after a crisis — like an overdose or involvement with the criminal justice system. Ideally, individuals in need of treatment should be identified earlier and referred to the appropriate level of treatment or counseling. (16)

DETOXIFICATION: Effective treatment begins with detoxification. Medically-assisted detox whether in an inpatient or outpatient setting helps individuals manage the symptoms of withdrawal under the supervision of medical and nursing professionals. (7)

TREATMENT: Because there is no one-size-fits all treatment program, treatment for SUD ranges from long-term inpatient care to short-term outpatient care. Different levels of treatment may be more or less effective depending on each individual’s specific needs and circumstances. In Tennessee, levels of treatment include (17) (7):

- Residential treatment, which delivers highly structured services in a 24-hour inpatient setting. Residential treatment can be short- or long-term ranging from just a few days to as much as a year.

- Halfway houses, which are residential programs that transition individuals from residential treatment to their communities.

- Non-residential rehabilitation, which includes outpatient, partial hospitalization, intensive outpatient, and day treatment programs. Depending on one’s circumstances, the latter 3 types can provide comparable levels of care to residential treatment sometimes requiring individuals to spend 8 hours a day in treatment.

Counseling is a key component of evidence-based treatment programs, which help individuals make behavioral changes and remain abstinent. Individual, group, or family counseling can, for example, help motivate individuals to change or build skills to resist drug use. (7)

Research has found that a combination of counseling and medication known as medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is the most effective treatment approach for opioid addiction. (7) (15) The FDA has approved 3 medications to treat opioid addiction: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone (Table 2). These medications help counter the effects of opioids on the brain relieving withdrawal symptoms, helping overcome drug cravings, and treating overdoses. However, they each come with risks and costs.

RECOVERY: Recovery support services involve less intensive continuing care that helps individuals abstain from drug use and live full, productive lives in their communities. Recovery services can include basic education, employment support, case management, peer support, family support, transportation, and spiritual support. (17)

Table 2. Medications for Treating Opioid Addiction |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| MEDICATION | Methadone | Buprenorphone (Bunavail, Suboxone, Zubsolv) | Naltrexone (ReVia, Depade, Vivitrol) |

| WHAT IS IT AND HOW IS IT TAKEN? | A synthetic opioid taken daily and administered orally (tablet, wafer, or liquid) | A synthetic opioid taken daily when administered orally or every 6 months when implanted | A synthetic opioid antagonist taken every 1-3 days when administered orally or monthly when injected by a provider |

| WHAT DOES IT DO? | Reduces the symptoms of withdrawals and blocks the effects of opioids | Reduces the symptoms of withdrawals and weakens the effects of opioids | Reverses overdose, blocks the effects of opioids, and reduces cravings |

| WHO PROVIDES IT? | Opioid Treatment Programs (OTPs) certified by SAMHSA | OTPs and other health care providers certified by SAMHSA/DEA (patient limits apply) |

Any doctor or pharmacist |

| WHAT ARE THE RISKS? | Can be addictive, result in overdose, interact with other medications, and cause heart conditions | Can be misused, particularly by people who do not have an existing opioid dependency | Can result in severe side effects if patient has not been detoxed for at least 7 days; can reduce tolerance and increase the chances of overdose in a relapse |

Note: SAMHSA = Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, DEA=Drug Enforcement Agency | Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse and SAMHSA (7) (18) (19) (20)

Barriers to Treatment and Recovery

Despite the known efficacy of treatment, many people face barriers to accessing the treatment and recovery services they need. These obstacles include financial obstacles, stigma, and treatment capacity.

Financial Obstacles

Insurance influences whether and to what extent individuals can afford treatment services, but even insured individuals can have trouble accessing needed treatment. (21) Most private health insurance plans must comply with the federal Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (MHPAEA). Under MHPAEA, plans that cover mental health and/or substance use disorder (MH/SUD) must make those benefits at least as generous as their medical and surgical benefits.

MHPAEA does not require insurance plans to cover MH/SUD benefits, but the Affordable Care Act does require MH/SUD coverage in the individual and small group markets. States are responsible for enforcing MHPAEA requirements for the individual market and many employer-provided plans. (22)

Despite these requirements, insurance practices like limited networks, utilization reviews, stricter medical necessity criteria, and low provider payment rates can make covered MH/SUD benefits harder to access. Some also argue that private insurers’ use of prior authorization for anti-addiction medicine reduces access to this part of treatment and violates MHPAEA. (23) Nationally, MHPAEA enforcement actions against plans have been relatively rare. (24) (25)

Certain low-income individuals — particularly pregnant women — rely on Medicaid (known as TennCare in Tennessee) for insurance coverage of needed treatment services. In 2016, the federal government required states (like Tennessee) that use managed care to deliver Medicaid benefits must also comply with MHPAEA. The new requirements take effect in October 2017. (26)

Low-income individuals without insurance coverage often rely on public safety net programs funded by the federal and state governments. Individuals without insurance who would self-pay may be put on waiting lists or have fewer options for treatment.

Stigma

Some view addiction as a moral failure and not a chronic disease, which increases social stigma. Patients may be reluctant to seek treatment for drug addiction or deny they have a problem, and physicians may struggle to have conversations about substance abuse with their patients. (27)

Using certain medications to treat opioid addiction may also carry stigma. Some argue that treating opioid use disorder with synthetic opioids (i.e. methadone and buprenorphine) simply trades one addiction for another. (28) However, the combination of therapy, support services, and MAT is highly effective for treating opioid abuse and the associated adverse health outcomes.

Treatment Capacity

Treatment is only available to the extent that providers and services exist and are accessible to the individuals who need them. “Taking advantage of available services the moment people are ready for treatment is critical,” according to NIDA. (7)

Mental health and addiction providers are concentrated in affluent urban and suburban areas. Recruiting and retaining providers in rural areas where opioid misuse is more prevalent can be difficult. Novel approaches like telemedicine may help address local capacity and provider distribution issues. Nationwide, however, there is a shortage of physicians specializing in addiction medicine. Addiction providers have lower wages, benefits, and reimbursement rates compared to other health care specialties. (29) (30)

Access to methadone, the most studied opioid abuse treatment medication, is particularly challenging. Methadone clinics are highly regulated and require daily visits from patients. If patients do not live near a clinic, treatment can be difficult. (9)

Demand and payment for treatment services heavily influences the capacity to provide them. What and how much Medicaid and private insurance plans pay for affects both whether individuals can afford treatment and the likelihood that providers go into related fields or offer those services. The stigma associated with addiction can also reduce demand for treatment services that people might otherwise seek.

Personal Barriers

In addition to stigma or denial, fear of treatment, previous negative experiences in treatment, privacy concerns, and lack of transportation can often prevent people from accessing treatment. Many individuals, particularly women, also have family obligations that keep them from entering treatment, such as taking care of children or family members. (31) (32)

Parting Words

Tennessee has made great strides in reducing the supply of prescription opioids by targeting prescriber practices. However, as the epidemic evolves, the state continues to see increases in the negative outcomes of opioid and heroin misuse and addiction. Understanding addiction, prevention, and treatment will be important as state policymakers consider next steps.

In Part 3 of this introductory series, we will examine the environment for prevention and treatment in Tennessee.

References

Click to Open/Close

- Volkow, Nora D., et al. Medication-Assisted Therapies — Tackling the Opioid-Overdose Epidemic. The New England Journal of Medicine. [Online] May 29, 2014. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1402780#t=article.

- U.S Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. [Online] November 2016. https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/surgeon-generals-report.pdf.

- McClellan, A Thomas, et al. Drug Dependence, a Chronic Medical Illness: Implications for Treatment, Insurance, and Outcomes Evaluation. JAMA, 284: 1689-1695. [Online] 2000. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3328/72f6b62af958c26393f514442e6178535c8f.pdf.

- U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Risk and Protective Factors. [Online] October 2, 2015. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-substance-abuse-prevention-early-childhood/chapter-2-risk-protective-factors.

- National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Among Children, Youth, and Young Adults. Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. [Online] 2009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK32789/#ch3.s6.

- U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Prevention of Substance Abuse and Mental Illness. [Online] https://www.samhsa.gov/prevention.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide. [Online] 2012. https://d14rmgtrwzf5a.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/podat_1.pdf.

- U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Behavioral Health Treatments and Services. [Online] https://www.samhsa.gov/treatment.

- National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. Guide for Policymakers: Prevention, Early Intervention and Treatment of Risky Substance Use and Addiction. [Online] December 2015. http://www.centeronaddiction.org/sites/default/files/Guide-for-policymakers.pdf.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Understanding Drug Abuse and Addiction: What Science Says. National Institutes of Health. [Online] February 2016. https://d14rmgtrwzf5a.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/1921-understanding-drug-abuse-and-addiction-what-science-says.pdf.

- U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Substance Abuse Prevention Dollars and Cents: A Cost-Benefit Analysis. [Online] 2008. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/cost-benefits-prevention.pdf.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Risk Factors for Prescription Opioid Abuse and Overdose. [Online] https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/opioids/prescribed.html.

- National Governors Association. Finding Solutions to the Prescription Opioid and Heroin Crisis: A Road Map for States. [Online] 2016. https://www.nga.org/files/live/sites/NGA/files/pdf/2016/1607NGAOpioidRoadMap.pdf.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. Public Policy Statement on Treatment for Alcohol and Other Drug Addiction. [Online] January 2010. https://www.asam.org/advocacy/find-a-policy-statement/view-policy-statement/public-policy-statements/2011/12/15/treatment-for-alcohol-and-other-drug-addiction.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Prescription Drugs: Abuse and Addiction. Research Report Series. [Online] 2011. https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/rrprescription.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. [Online] 2016. https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/surgeon-generals-report.pdf.

- Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (TDMHSAS). Rules of the Office of Licensure. [Online] 2017. http://share.tn.gov/sos/rules/0940/0940-05/0940-05.htm.

- U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Medication and Counseling Treatment: Naltrexone. [Online] September 12, 2016. https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/treatment/naltrexone.

- —. Medication and Counseling Treatment: Methadone. [Online] September 28, 2015. https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/treatment/methadone.

- —. Medication and Counseling Treatment: Buprenorphine. [Online] May 31, 2016. https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/treatment/buprenorphine.

- Nosyk, Bohdan, et al. A Call For Evidence-Based Medical Treatment Of Opioid Dependence In The United States And Canada. Health Affairs 32(8). [Online] August 2013. http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/32/8/1462.full#ref-39.

- United States Government. Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. [Online] 2008. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Health-Insurance-Reform/HealthInsReformforConsume/downloads/MHPAEA.pdf.

- Luthra, Shefali. Facing Pressure, Insurance Plans Loosen Rules for Covering Addiction Treatment. Kaiser Health News. [Online] February 21, 2017. http://khn.org/news/facing-pressure-insurance-plans-loosen-rules-for-covering-addiction-treatment.

- Goodell, Sarah. Enforcing Mental Health Parity. Health Affairs and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. [Online] November 9, 2015. http://healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief_pdfs/healthpolicybrief_147.pdf.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. A Long Road Ahead: Achieving True Parity in Mental Health and Substance Use Care. [Online] April 2015. https://www.nami.org/About-NAMI/Publications-Reports/Public-Policy-Reports/A-Long-Road-Ahead/2015-ALongRoadAhead.pdf.

- U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicaid Fact Sheet: Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Parity Final Rule for Medicaid and CHIP. [Online] March 29, 2016. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/downloads/fact-sheet-cms-2333-f.pdf.

- Parks, Troy. How to talk about substance use disorders with your patients. American Medical Association (AMA) Wire. [Online] https://wire.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/how-talk-about-substance-use-disorders-your-patients.

- Vestal, Christine. In Drug Epidemic, Resistance to Medication Costs Lives. The Pew Charitable Trusts. [Online] January 11, 2016. http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2016/01/11/in-drug-epidemic-resistance-to-medication-costs-lives.

- American Hospital Association. The State of the Behavioral Health Workforce: A Literature Review. [Online] 2016. http://www.aha.org/content/16/stateofbehavior.pdf.

- Hoge, Michael A, et al. Mental Health and Addiction Workforce Development: Federal Leadership is Needed to Address the Growing Crisis. Health Affairs 32(11). [Online] 2013. http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/32/11/2005.full.pdf.

- Rapp, Richard C, et al. Treatment barriers identified by substance abusers assessed at a centralized intake unit. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30(3), 227-235. [Online] 2006. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1986793/

- Hancock, Christine, et al. Treating the Rural Opioid Epidemic. National Rural Health Association. [Online] February 2017. https://www.ruralhealthweb.org/NRHA/media/Emerge_NRHA/Advocacy/Policy%20documents/Treating-the-Rural-Opioid-Epidemic_Feb-2017_NRHA-Policy-Paper.pdf

Featured Image at top by airpix / CC BY 2.0