In recent years, Tennessee has amassed some of its largest budget surpluses ever while at times facing the prospect of equal or even larger deficits. Since the budget must balance, situations like these confront policymakers with significant tax and spending decisions. Yet even with the best revenue and spending forecasts, underlying trends and unexpected changes in the economy can limit their options.

This brief explains how surpluses and deficits occur, the role of revenue projections and rainy day funds, and the trade-offs Tennessee’s governor and General Assembly must weigh when crafting the budget. For even more on these topics, check out Sycamore’s Tennessee State Budget Primer.

Key Takeaways

- Excess revenues occur as either mid-year budget adjustments or end-of-year surpluses. They can fund one-time investments in current or future fiscal years.

- Deficits occur when spending exceeds revenues. Cyclical deficits result from economic downturns while structural deficits reflect more fundamental imbalances in budget policy.

- Rainy day funds provide a cushion that helps policymakers avoid or minimize the difficult decisions that recessions sometimes require.

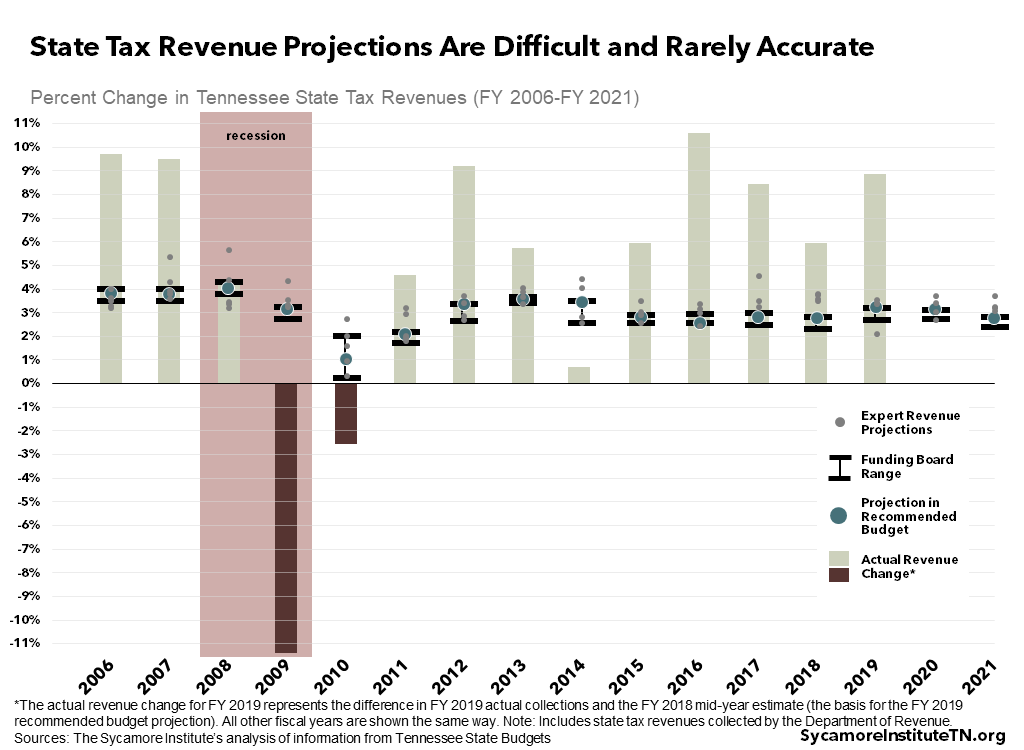

- Recent history suggests state tax revenue projections are difficult and rarely accurate. Tennessee’s conservative forecasts help the state avoid deficits, make surpluses more likely, and allow for one-time investments like rainy day savings.

- The main trade-off to surpluses and savings is that policymakers could have used the money for recurring policy priorities, such as programs, services, or tax relief.

Surpluses

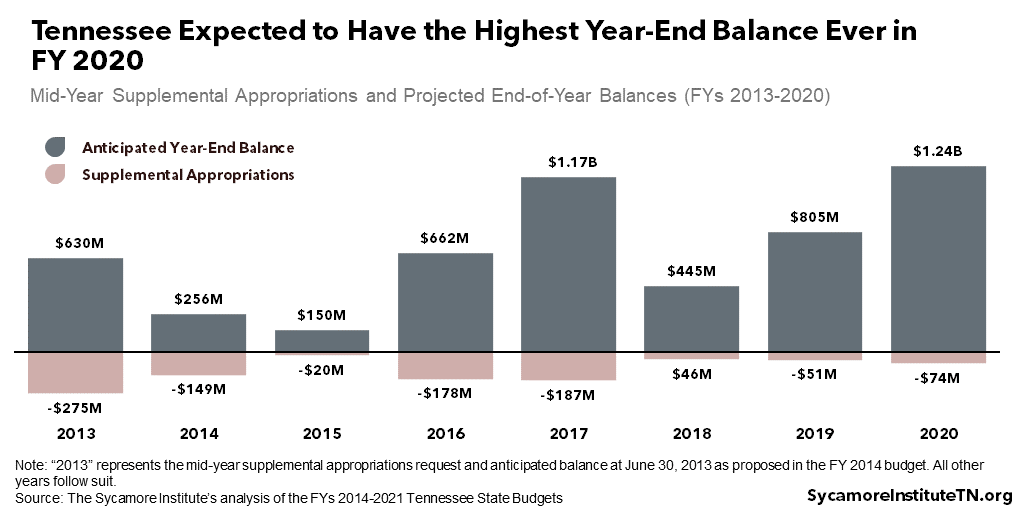

A surplus occurs when Tennessee has either collected more or spent less money at the end of a fiscal year than lawmakers approved in the budget. The state cannot use this leftover money in subsequent years until the General Assembly decides how to allocate it. Figure 1 shows how these surpluses have varied since FY 2012. (1) (2) In more precise terms:

- When revenue collections outpace budgeted estimates, the state accumulates a surplus that it cannot yet spend. This type of surplus is known as an “overcollection.” At the end of a fiscal year, this excess revenue goes into the Reserve for Future Requirements until lawmakers appropriate it for a specific purpose.

- Surpluses can also accumulate when programs spend less than their appropriation. At the end of a fiscal year, some programs with unspent appropriations can roll over all or part of their savings into a program reserve for future years. Most other unspent General Fund revenues revert back to the General Fund and go into the Reserve for Future Requirements. [i]

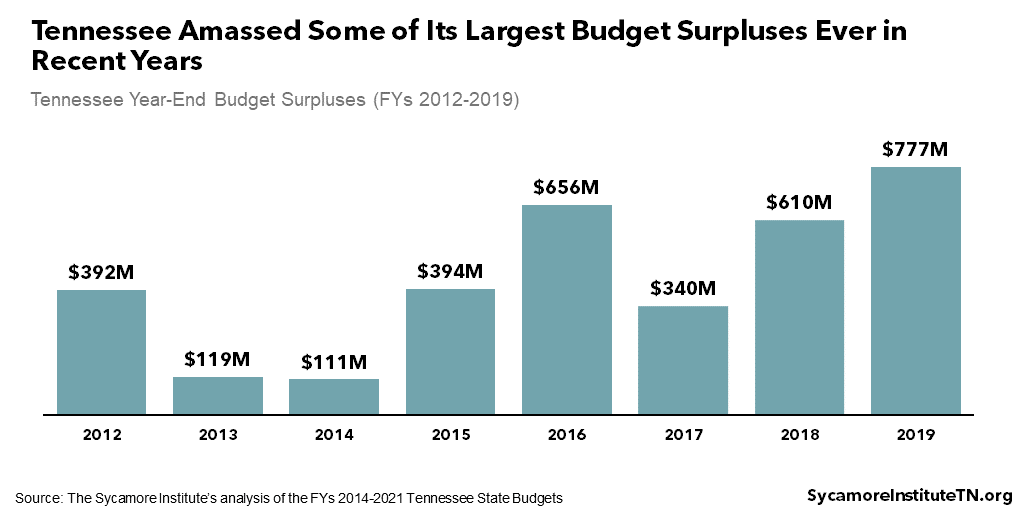

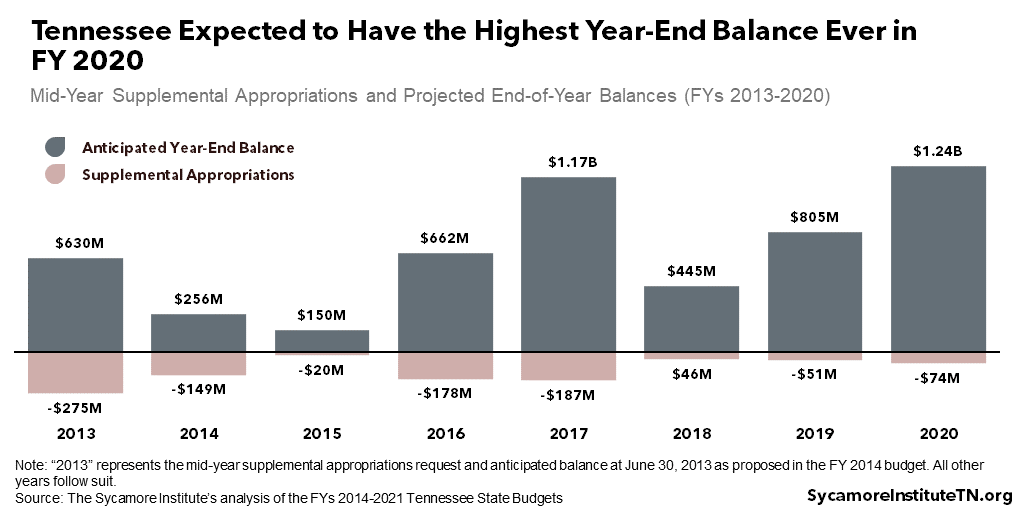

Official mid-year revenue and spending re-estimates in each year’s budget can also yield additional funds that were not anticipated when the fiscal year began, but this money is not considered “surplus.” For example, the most recent budget proposed by Gov. Lee in January projects $539 million in additional FY 2020 General Fund revenues that were not budgeted at the start of the fiscal year. Of this amount, $500 million comes from an increase in expected tax collections. Figure 2 displays how mid-year re-estimates have varied since FY 2013. (1) (2)

Figure 1

Figure 2

Surpluses and mid-year revenue re-estimates can fund one-time investments. For example, the FY 2021 recommendation uses some of the $777 million FY 2019 surplus (Figure 1) and the $539 million in FY 2020 mid-year adjustments (Figure 2) for $74 million in FY 2020 supplemental appropriations. The remaining $1.2 billion carries over as non-recurring revenue for FY 2021 (Figure 3) — the highest projected year-end balance in recent history.

Most other unspent fund balances Tennessee carries from year to year are tied to specific purposes. At the end of FY 2019, the state had a total balance of about $6.4 billion across the General, Education, and Highway Funds. (1) Aside from year-end surplus in the Reserve for Future Requirements, these balances have specific purposes required either by state law or by strings attached to their revenue source, such as the federal government. They are not available to spend on other purposes. Examples include rainy day funds, one-time appropriations for construction, road, or other projects that span multiple years, and fees that pay for specific programs or agencies, such as licensing boards.

Figure 3

Deficits

Deficits occur when spending exceeds revenues. There are two basic types of budget deficits, cyclical and structural, which differ in significant ways.

Cyclical Deficits

Cyclical deficits can occur when economic downturns throw revenues and spending out of balance. Even with the best year-to-year and mid-year revenue and spending estimates, unexpected economic conditions and underlying trends can challenge the state’s ability to balance its budget as constitutionally required.

Economic downturns create higher-than-usual demand for programs and services while reducing the revenues that fund them. Personal income falls during recessions, which curtails personal spending and shrinks the state’s sales tax revenue. At the same time, more people typically enroll in state-funded programs to help bridge the gap. Unexpected events like natural disasters and public health emergencies can also increase demand for state assistance.

Because the budget must balance, Tennessee cannot end its fiscal year with a deficit. When facing the prospect of a deficit, policymakers have to actively manage the budget mid-year by cutting spending, raising revenues, tapping rainy day funds, or some combination thereof. During the Great Recession of 2007-2009, Tennessee drew down reserves, reduced recurring spending, and froze state employee salaries. The state tapped almost $800 million combined from the Reserve for Revenue Fluctuations and the TennCare Reserve over the course of the recession and recovery. (1)

Structural Deficits

A structural deficit arises from a fundamental imbalance in budget policy that causes spending to exceed revenues. It differs from a cyclical deficit, which stems from temporary factors like an economic downturn. The term structural deficit can refer to two situations:

1) Current revenues cannot pay for current programs.

2) Long-term forecasts anticipate spending will grow faster than revenue over time.

Identifying both if and why a structural deficit exists is necessary but can be difficult and subjective. Tennessee’s incremental budget process was not designed to confront many of the broad policy questions inherent in both questions.

It can be tough to identify a structural deficit in budgets that must balance every year. The growing national debt makes it easy to see a structural deficit in the federal budget. However, since Tennessee’s annual revenues and expenditures must balance, determining if the state budget has a structural deficit can be harder and subject to interpretation. Sycamore’s Tennessee State Budget Primer lays out a few potential methods to identify if a structural deficit exists.

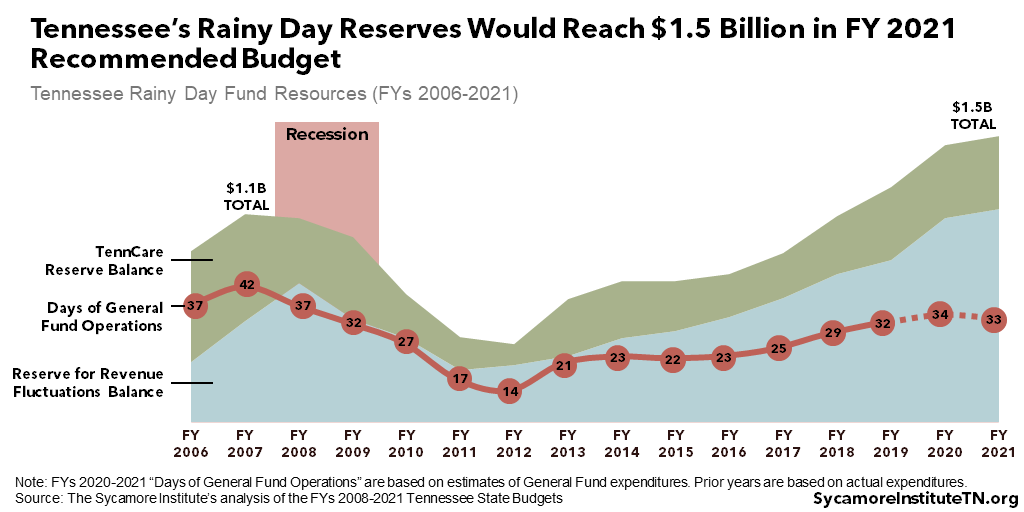

Figure 4

Rainy Day Funds

Rainy day funds help policymakers smooth out the ups and downs of the economic cycle. Rainy day funds allow states to set money aside when revenues are strong and/or demands are relatively low. States can then tap those reserves when revenues are weak and/or demands increase.

The Reserve for Revenue Fluctuations and the TennCare Reserve together represent Tennessee’s ability to respond to a downturn. The former is specifically for unexpected changes in revenue collections. The latter is a separate fund that holds excess dollars for TennCare. In dire situations, the legislature can make the TennCare Reserve available to shore up both TennCare and the larger General Fund.

Rainy day funds are also important for maintaining Tennessee’s AAA credit rating. Credit rating agencies set a state’s rating after determining its financial obligations and its ability and will to meet those obligations. Large reserves that can fill unexpected budget gaps are especially important for states with less political appetite to raise revenue.

The Reserve for Revenue Fluctuations balance is made up of a series of one-time deposits — usually from budget surpluses. Surpluses, however, do not automatically go into the Reserve. The amount deposited each year depends on the Reserve’s target balance as specified in the annual appropriations bill. This target balance determines the size of the deposit even if the state has a larger surplus and could “afford” to set aside more.

Gov. Lee proposed adding $50 million to the Reserve for Revenue Fluctuations in the FY 2021 budget, for a combined balance with the TennCare Reserve of $1.5 billion (Figure 4). This combined balance would cover about 33 days of state-funded General Fund operations at the FY 2021 recommended spending levels — about 21% less cushion than just before the Great Recession. (1) (2)

State Tax Projections

The accuracy of state tax projections plays a major role in whether surpluses and deficits occur. Conservative forecasts contribute to surpluses. Meanwhile, when projections are higher than actual collections, policymakers may face difficult decisions to make ends meet.

How Tennessee Projects Revenues

State law lays out the process for projecting state revenues. (3) (4) (5) Each year’s budget is based on an expected revenue range from the State Funding Board, whose recommendation is informed by the advice of experts. The Funding Board consists of the governor, the commissioner of finance and administration, the comptroller, the secretary of state, and the treasurer. The Funding Board typically gets separate revenue estimates from:

- The Fiscal Review Committee.

- The Department of Revenue.

- Outside economists (for example, from the University of Tennessee’s Boyd Center for Business and Economic Research and East Tennessee State University’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research).

The Funding Board uses the expert estimates to recommend a range of revenue predictions for the upcoming fiscal year, as well as a revised range for the current fiscal year. The Funding Board’s range usually encompasses at least some of the expert projections. In some years, they have recommended a range below that of any of the expert estimates but, at least in recent history, never above (Figure 5). (1)

Finally, the governor and budget staff use the Funding Board’s range to select an official revenue projection for the recommended Budget. The governor’s proposals for spending and revenue changes are based on this official estimate.

Figure 5

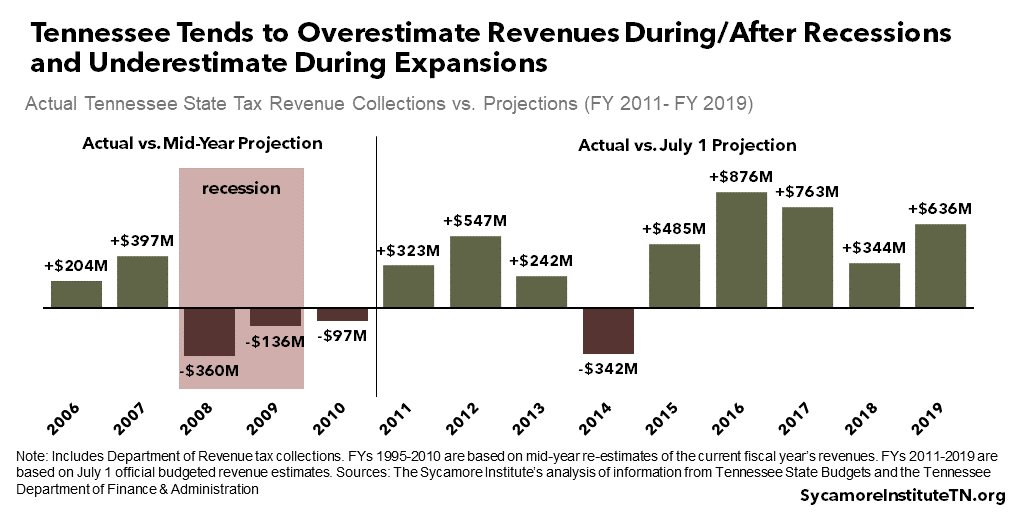

Projection Accuracy

Recent history suggests that state tax revenue projections are difficult and rarely accurate. (6) Based on recent experience, Tennessee tends to overestimate its tax revenues during and immediately after recessions and underestimate them during times of economic growth (Figures 5 and 6). (1) (7)

The state reports its revenue collections every month, which lets policymakers and the public see how actual revenues compare to the estimates on which the Budget was based. The Sycamore Institute tracks the reports monthly with our Tennessee Tax Revenue Tracker.

Figure 6

The Trade-Offs

Both surpluses and savings come with trade-offs. Surpluses represent conservative budgeting that reduces the likelihood of imbalances that can confront policymakers with difficult choices to make ends meet. Surpluses also allow the state to make one-time investments in the rainy day fund or other non-recurring priorities. Meanwhile, the rainy day fund helps smooth out the ups and downs of the economy and can insulate policymakers from the difficult choices that may arise from those ups and downs. The trade-off, however, is that both surpluses and savings represent revenues that could have been used for recurring policy priorities (e.g. spending for programs and services, tax relief).

References

Click to Open/Close

- State of Tennessee. Information from the FY 2006-FY 2020 State Budgets. [Online] Available via https://www.tn.gov/finance/fa/fa-budget-information/fa-budget-archive.html.

- —. FY 2021 Tennessee State Budget. [Online] February 3, 2020. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/finance/budget/documents/2021BudgetDocumentVol1.pdf.

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 9-4-5202 (2019). [Online] https://advance.lexis.com/api/document/collection/statutes-legislation/id/4X8K-SDH0-R03M-30M2-00008-00?cite=Tenn.%20Code%20Ann.%20%C2%A7%209-4-5202&context=1000516.

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 9-4-5104 (2019). [Online] https://advance.lexis.com/api/document/collection/statutes-legislation/id/4X8K-SDH0-R03M-30KK-00008-00?cite=Tenn.%20Code%20Ann.%20%C2%A7%209-4-5104&context=1000516.

- —. Tenn. Code Ann. § 9-4-5105 (2019). [Online] https://advance.lexis.com/api/document/collection/statutes-legislation/id/4X8K-SDH0-R03M-30KM-00008-00?cite=Tenn.%20Code%20Ann.%20%C2%A7%209-4-5105&context=1000516.

- National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO). “Table: General Fund Revenue Collections Compared to Projections” from The Fiscal Survey of States (Fall 2015, Fall 2016, Fall 2017, Fall 2018, Fall 2019). [Online] Accessed via https://www.nasbo.org/mainsite/reports-data/fiscal-survey-of-states/fiscal-survey-archives.

- Tennessee Department of Finance and Administration. July 1 Revenue Estimates for FY 2011 – FY 2019. [Online] Accessed from https://www.tn.gov/finance/fa/fa-budget-information/fa-budget-rev.html.

[i] Some underspending/reversion is assumed in the budget’s “overappropriation.” Only the reversion amounts in excess of the appropriation become part of the Reserve for Future Requirements. For more information about the overappropriation, see our Tennessee State Budget Primer.

*This policy brief replaced one on similar topics that was published on Jan. 10, 2017.